Food and food preparation in the films of Studio Ghibli evoke a sense of geborgenheit – security, comfort, and emotional warmth, says Sophie Lovell. In the Ghibli foodiverse, food is hearth and home, conjuring a sensual state of longing and belonging.

Food has a lot of symbolic meaning in storytelling, and this is particularly enhanced when tied to the ancient domestic place of preparation: the hearth. The term comes from the Old English heorð, which means “household” or “settled home”. It is probably safe to say that for most of human existence, the hearth has been the universal heart of the home as a source of heat, nourishment and gathering. Food, hearth, and humanity are inextricably bound together; it is no coincidence that the Greek word kardia, for example, means both “hearth” and “heart”.

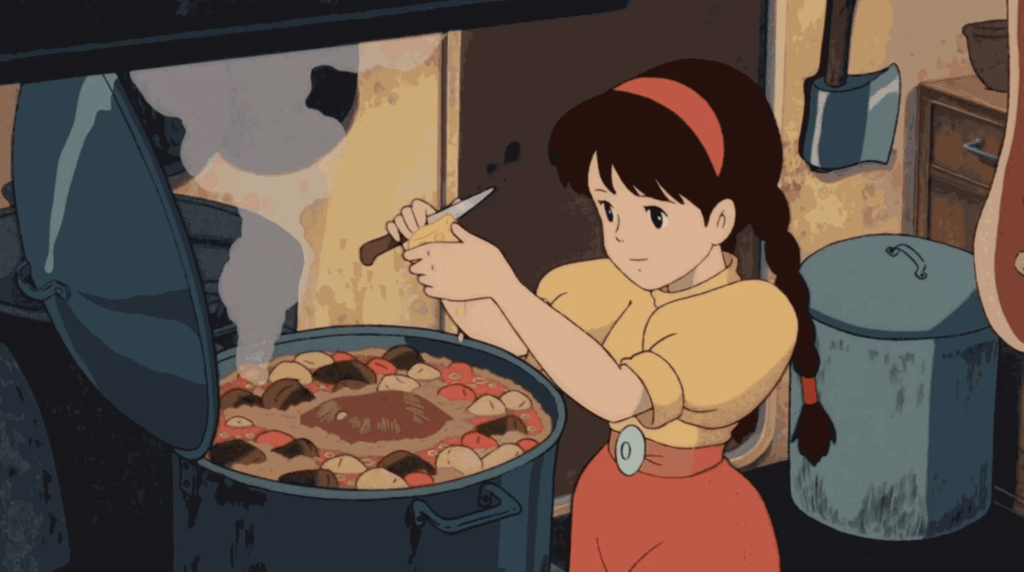

In Japanese culture, too, the sunken irori or hearth is the traditional physical and spiritual centre of the home, something that is made beautifully clear again and again in the many films of Studio Ghibli, founded in Tokyo in 1985 by Hayao Miyazaki, Isao Takahata and Toshio Suzuki. In the feature-length works of this animation studio, the recurring representation of food preparation and consumption is frequently a reflection of that ancient spirit of the hearth. In the Ghibli foodiverse, food is not just nourishment; it is an act of love, a ritual of care, and a medium of connection.

In the Ghibli foodiverse, food is not just nourishment; it is an act of love, a ritual of care, and a medium of connection.

Often in the form of simple home-cooked meals, Ghibli food is the best kind of food. Its unusually tactile, intimate, and reverent portrayal frequently becomes a visual and thematic shorthand for geborgenheit in that it evokes a profound sense of security, comfort, and emotional warmth; a state of being held or sheltered both physically and emotionally. Maybe also with a little longing.

The preparation, textures, and slowness of food scenes in Ghibli films, such as the clatter of bowls, steam rising from soups, and the slurping sounds of characters eating, all evoke sensory comfort; a sort of cinematic version of a warm hug. As such, food-sharing scenes become grounding moments, particularly for characters who are displaced, in transition or emotionally isolated.

In My Neighbour Totoro (1988), Spirited Away (2001), or Howl’s Moving Castle (2004), for example, kitchens are not just backdrops; they are sacred spaces of transformation and restoration. Think of the scene with Howl frying a breakfast of eggs and bacon and sharing it with Sophie and Markl. In it, the stove is a literal hearth, with Calcifer as the flame, a living heart. Or of Chihiro being offered food by Kamaji and Lin in Spirited Away in small gestures that signify trust, acceptance, and protection. The hearth in these films is where characters nurture each other, often in moments of transition, grief, or bonding, echoing again those ancient associations of the hearth as the centre of familial and communal life.

Ghibli characters rarely say “I love you” outright; instead, they cook for each other. In From Up on Poppy Hill (2011), Umi prepares breakfast with quiet dedication. This daily ritual is her way of holding her family together. In Ponyo (2008), Ponyo and Sōsuke’s shared meal of ramen becomes a symbol of comfort and affection – warm food on a rainy day, enjoyed together with a friend. At the other end of the spectrum is the heart-wrenching scene of the starving child Setsuko trying to feed her brother Seita rice balls made of mud in Grave of the Fireflies (1988). Here, food becomes a non-verbal expression of care, hospitality, and grief.

This daily ritual is her way of holding her family together.

Characters in the Ghibli foodiverse are often shown eating together and food is often used to symbolise belonging. In creating new bonds between characters, meals provide temporary homes as well: Kiki sharing a meal with Ursula or being fed by Osono in Kiki’s Delivery Service, for example. In Spirited Away, Haku tells Chihiro to eat food from the spirit world so she won’t disappear, so food literally anchors her to that world and gives her a place in it.

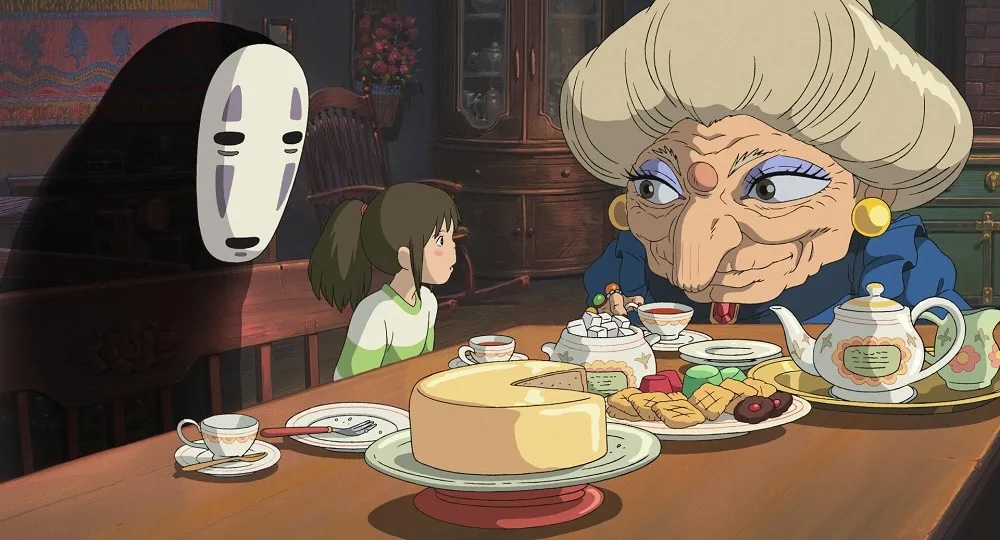

Of course, food in the Ghibli world is not always a source of comfort; sometimes it can be symbolic of danger, greed or moral compromise. Nowhere is that more clearly the case than when Chihiro’s parents gorge themselves on the spirit food and are literally turned into pigs, or the feast for the spirit No-Face, in Spirited Away, which was a sharp criticism of the effect of Western greed on Japanese culture at the time. Rather than being about geborgenheit, these food scenes have more to do with suggesting loss of control and spiritual corruption; in other words, not safety, but vulnerability.

Whatever it may represent, food in Ghibli films is a huge “thing”. People make compilation YouTube videos about it, and there are cookbooks, TikTok channels and anime ASMR discourses dedicated to it. Ghibli’s own Grand Warehouse in Aichi, Japan, has a permanent exhibition, called “Delicious! Animating Memorable Meals Expanded Edition”, devoted entirely to their food content. All of which is totally understandable if you have ever got lost in the beauty and weirdly nostalgic wonder of a Ghibli character making a pot of soup. Yes, it tends to reflect particular forms of gendered domesticity, yes, that seductive nostalgia feeling might be ringing faint alarm bells somewhere in the back of the mind, but a big, warm helping of conviviality in the form of comfort food could be what we all need right now – even if only vicariously.

Cover image: Still from Spirited Away (2001), All images © Studio Ghibli