There’s a beautiful word in Korean, son-mat, which translates as “hand taste” and belongs to a fermentation culture that is over 3,000 years old. The artist, bio-designer and researcher Jiwon Woo’s project “Mother’s Hand Taste” explores whether the taste of the hand, i.e. the flavour imparted to fermented foods by the unique microflora of the hands of the family member preparing them, can be transmitted through generations and across continents. It is a project that could have big consequences for the understanding of legacy.

My investigation Mother’s Hand Taste was named after the Korean word son-mat, which literally translates as “hand taste”, but also means something like “a mother’s care”. The project explores how a person’s individual hand microflora impacts the development of flavour in fermented foods. It led me to trace, record and eventually bio-fabricate the hand microbiome of different generations of the same families, living in a variety of countries.

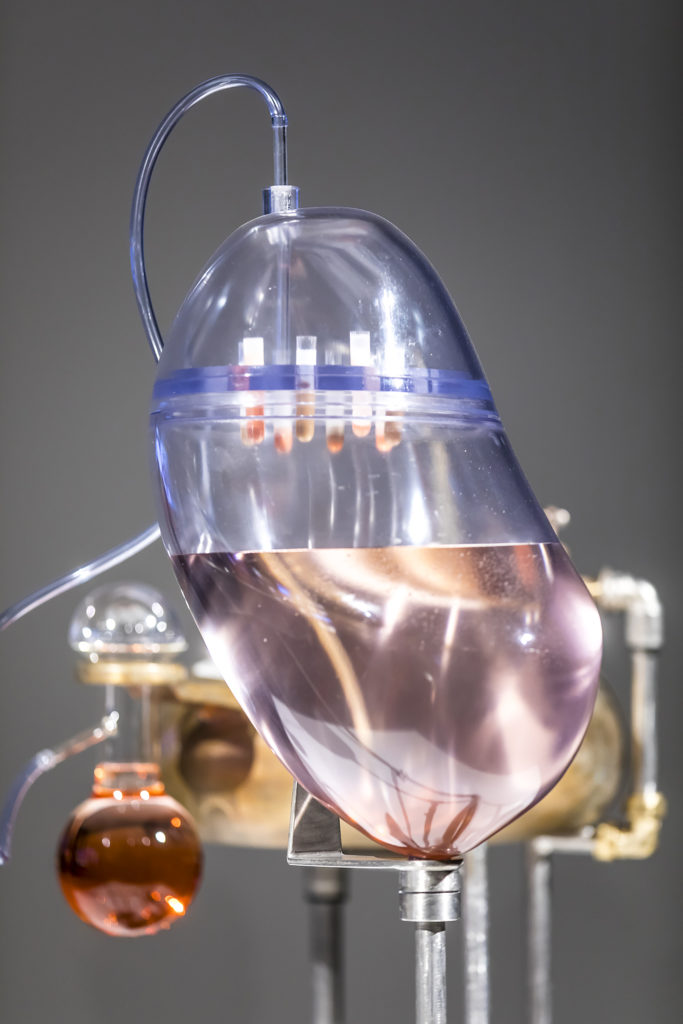

If the knowledge and experience of cooking represent intangible cultural inheritance, son-mat is an amplification of that. My research and the resulting mechanical machine designed to capture and reproduce a person’s son-mat is a poetic but tangible way of crystallising the elusive essence of ethnic and genealogical food culture. By investigating “hand taste” through artistic, scientific, and technological means, I reflect critically on the origins, authenticity and preservation of cultural heritage. The main outcome of the project is the creation of a conceptual and mechanical machine aimed at capturing, storing and growing one’s own son-mat.

Concept

The contact between food and the hands of the cook is an essential part of Korean cuisine. The Korean word son-mat, meaning “hand taste”, relates to a compliment in response to excellent culinary abilities. If someone is a good cook, the compliment would express that that person possesses good “hand taste”. Significantly, the word also connotes associations to family history, particularly the wisdom of ancestors and gratitude toward nature. Son-mat is a mechanism for triggering special memories and a deep sense of belonging through the act of eating, as the knowledge of producing a particular son-mat is a quality passed down generationally.

If someone is a good cook, the compliment would express that that person possesses good “hand taste”.

The Mother’s Hand Taste project involved genealogical research on hand microbiomes and their influence on food taste, a visualised replication of son-mat, and a ritualistic “hand-infecting machine” aimed at preserving son-mat. By handling and observing these objects, visitors will be encouraged to think critically about the significance of cultural identity, heritage and the passing down of invisible experiences in artistic, scientific, and sociological perspectives.

Process

The project started by selecting four three-generation Korean households (grandmother, mother, daughter) from four historically relevant countries (Korea, Japan, the United States and the Netherlands) with different eating habits. For the artistic documentation, I needed to understand each family’s history, dynamics, eating habits, and learning them in their specific respective country settings.

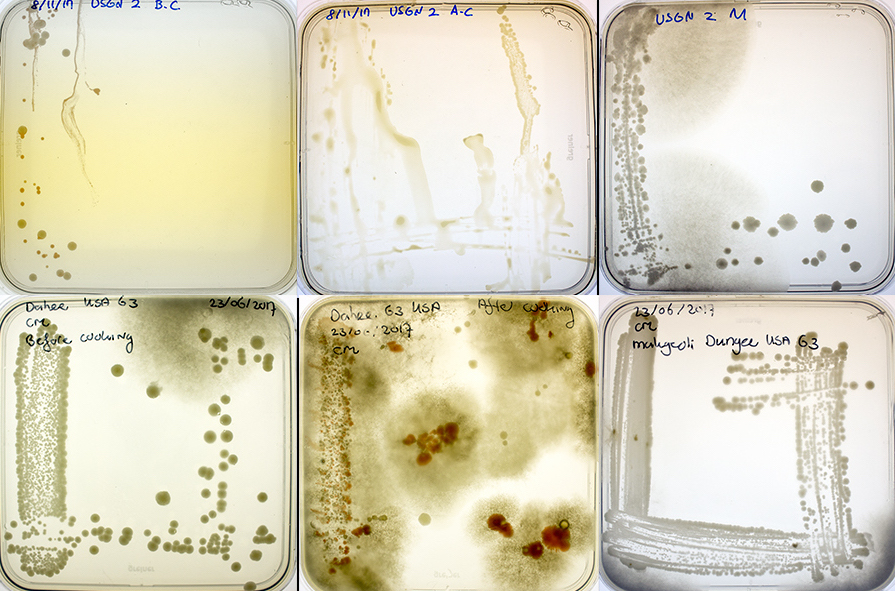

In parallel, the first set of hand fungi from each member of the three generations was collected according to a protocol provided by Han Wösten, Professor of Microbiology at Utrecht University. The subjects all individually cooked the same traditional fermented drink, Makgeolli. After cooking, a second set of hand fungi was collected from the subjects together with their dishes. Along with the cooking process, the emotions between the generations within the households were recorded. Towards the end of my interactions with the subjects, environmental portrait and photographs of the hands of each subject were taken.

Collaboration

Professor Wösten is an expert in fungal growth and development and his work is part of the Future Food programme of Utrecht University. The hand yeasts of 12 participants were cultured, purified, identified, and compared between the households, the generations and times of sampling at his Microbiology Department. We also investigated the different influences that the various hand yeasts have on the taste of traditional fermented food. Colonies of the hand yeasts in different dimensions and shapes were grown in order to physicalise and visualise the invisible organisms inhabiting the subjects’ hands.

We worked together to research the genealogical relationships between yeasts, the yeasts’ influence on the fermentation of foods, the appropriation of these yeasts as artistic material, and the appropriation of these yeasts as new material. This collaboration enabled the expansion of the genealogically-oriented formulation of son-mat into a cross-cultural understanding.

Three out of four of the families showed similarities and a continuation of hand yeasts across three generations, regardless of their geographical locations.

Once the purified yeast cultures of all participants were ready, they were identified using a Remel RapID Yeast panel test. The yeast cultures were then compared among family generations, countries of origin and time of sampling. We discovered that three out of four of the families showed similarities and a continuation of hand yeasts across three generations, regardless of their geographical locations.

Makgeolli

With its long history in relation to politics, economy, social class, and colonialism, Makgeolli has been chosen by Woo to be incorporated in the Mother’s Hand Taste (Son-mat) project. Both commercial and family inherited Nuruk, fermentation starter (that is over 60 years old), were examined and used both artistically and scientifically.

Makgeolli is a traditional Korean alcoholic beverage, with more than 1,700 years of history. It is made by combining cooked sticky rice, water and a starter culture called Nuruk. It is milky-white, fizzy and refreshing. It is also called “Nongju”, which means “farmer’s wine” because it is made mostly of rice and was traditionally often drunk by farmers as part of their mid-morning snack or with lunch. Nuruk is a dry cake of wheat, barley, and rice that hosts a variety of wild yeasts, bacteria, and Aspergillus Oryzae, Aspergillus Nigar and Aspergillus Kawachii mould spores.

“If I have good son-mat that means I inherited a great fortune”

Making the family’s own special Nuruk culture and the home-brewing of Makgeolli faded under Japanese colonisation when all alcohol-making activity in Korean households was forbidden as part of a programme of Korean culture obliteration. After liberation from Japanese occupation, there was another government prohibition, this time under President Park Chung-hee because of the economic slump and lack of food following the Korean War. It was during this time period that some variations in Makgeolli occurred and it began to be made using wheat, corn and other grains.

Mother’s Hand Taste

I chose three unique, innocuous yeasts cultured from the families to work with for my machine: Trichosporon Beigelli, Rhodotorula Rubra, and Rhodotorula Minuta. In the creating of my Mother’s Hand Taste machine, I imagined capturing my mother’s son-mat and preserving it so that I could transmit it to my own hands whenever I missed the taste of her food. With this machine, the user can capture and grow the son-mat of anyone and then preserve and propagate it, finally transferring it onto her own hands. Then the user can cook and ferment her own Makgeolli and it will have the “hand-taste” preserved and propagated by the machine.

Mother’s Hand Taste emphasises the importance of science in the context of sociology and culture. It considers what is to be maintained and preserved and what is to be left behind or developed for the future.

Jiwon Woo is a multidisciplinary designer, artist, and researcher. She integrates biology, creativity, and technology to deliver new design studies that suit both modern society’s needs and ecological sustainability. Her project Mother’s Hand Taste received the Lawrence Shprintz MFA Award from PennDesign, was the Final Winner of the BAD (Bio Art and Design) Award 2017, received an honorary mention at Prix Ars Electronica of Ars Electronica 2019: Out of the Box in the Artificial Intelligence & Life Art sector, and has been showcased at V&A Museum’s exhibition FOOD: Bigger than the Plate in 2019.

Title image: “Mother’s Hand Taste” machine by Jiwon Woo (all images courtesy Jiwon Woo).