Industrial-scale meat production is part of an outdated and destructive system. We need to change how we think about it and that includes what we feed our pets. Berlin-based Eat Small is carving a niche for itself with an insect-based dog food range that offers a more circular alternative.

Humans have a very unbalanced relationship with their domesticated animals, one that is neither good for the planet – nor the animals. Firstly, we are very keen on eating our furry and feathered friends and doing so on a terrifying scale. In 2018, according to the UN Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO), an estimated 69 billion chickens; 1.5 billion pigs; 656 million turkeys; 574 million sheep; 479 million goats; and 302 million cattle were slaughtered worldwide for meat production alone. Food production is responsible for around one-quarter of global greenhouse emissions and at least 31 per cent of that comes from livestock and fisheries.

Ethical issues aside, it is common knowledge that reducing meat consumption would not only help reduce greenhouse consumption significantly but also aid the reduction of world hunger, rebalancing of ecosystems and reduce water shortages. But humans are not the only meat consumers within our food system, which leads us to the second part of the domestication relationship: we have a tendency to surround ourselves with an awful lot of meat-eating pets as well. A conservative estimate of the global number of pet dogs, for example, is around 470 million and rising. According to a recent article in The Guardian, there are now 12 million pet dogs in the UK alone – a figure that is up a remarkable two million in the last twelve months thanks to the “lockdown puppy” companion phenomenon.

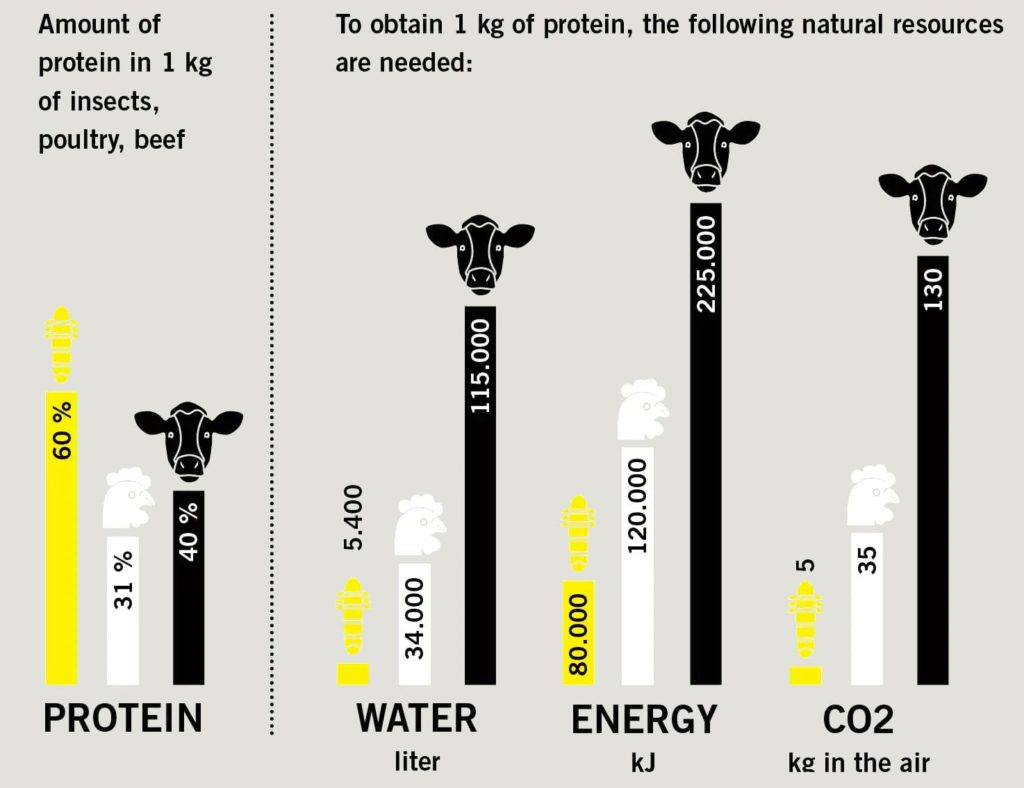

For most humans, eating animals is a choice. Although it provides a rich source of protein, we don’t biologically need to eat meat if we have access to sufficient variety of other foodstuffs, but our pet dogs and cats do require animal protein to thrive – and plenty of it. Supplying a growing global population of 7.9 billion humans and their pets with a sustainable source of animal protein is one of the biggest challenges of the 21st century. A viable alternative protein source that has been bandied around for a long time is insects. In terms of production, insects require little water, food and space compared to poultry and beef, and their mass to protein ratio can be far higher: mealworm meal, for example, contain 72 percent protein compared to an average 48 per cent in beef meal.

Despite being a popular staple in some culinary cultures, insect protein has been slow to make its way into the mass mainstream human diet. For pets, on the other hand, there is a bit of a revolution going on. Four years ago, a Canadian veterinarian Véronique Glorieux and Spanish graphic designer Gema Aparicio co-founded a company they called Eat Small in Berlin, seeking to create dried dog food made with alternative protein and carbohydrate source. Their goal was to reduce the ecological footprint of domestic dogs “one bag of pet food at a time”.

For pets there is a bit of a revolution going on.

“By offering dogs a quality insect-based food, we are directly participating in strengthening the links towards a circular economy involving insects,” says Véronique, “An ideal insect farm model would integrate 100 per cent of so-called co-products from the agri-food industries (a good example is brewery residues). The insect species we use can efficiently convert tonnes of food waste into valuable products, including high quality proteins for our pet companions.”

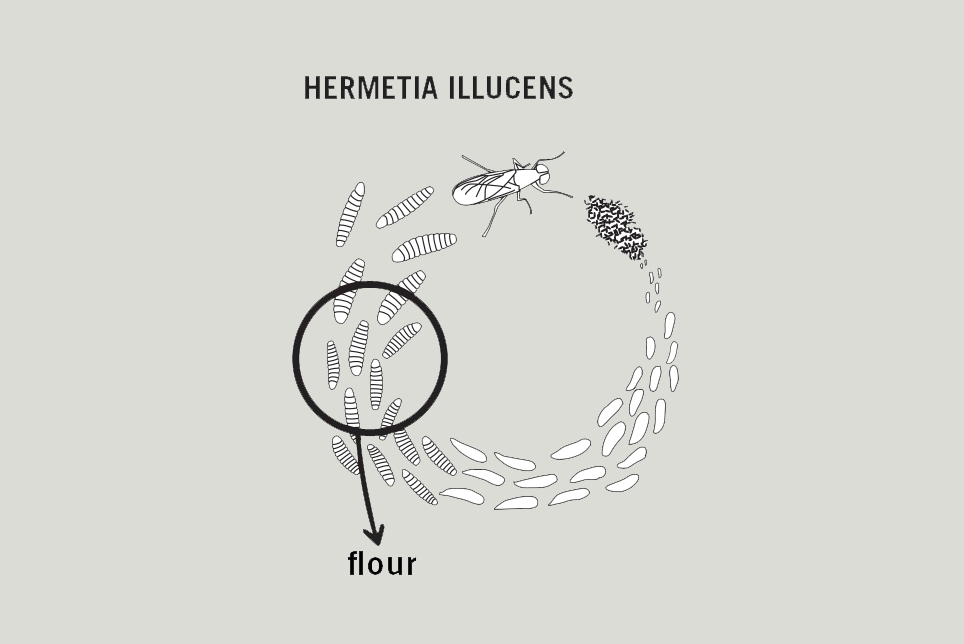

Véronique and Gema spent a year sourcing producers of black soldier fly larvae (Hermetia illucens) and mealworms (Tenebrio molitor), and devising recipes for tasty, balanced and nutritious food products geared towards dogs. They eventually found suppliers in the nearby German state of Brandenburg as well as in France and Bulgaria. The resulting Eat Small products contain insect protein and alternative grains such as amaranth, gold millet, and lentils. The insect-based formula, say Véronique and Gema, is particularly helpful for resolving allergies amongst dogs that result from the meat protein in standard pet food formulae.

An Eat Small insect-based cat food is also in the pipeline but getting the recipe right for cats is a little trickier, says Véronique. Unlike dogs, they are obligate carnivores and their digestive systems don’t take kindly to cereals and carbs and need supplements such as taurine to stay healthy.

The ecological reasoning for using insects instead of meat in pet food is clear. The greenhouse gas emissions and carbon footprint from insect production are nowhere near the scale of conventional industrial meat production. Black soldier flies, for example, are grown commercially in an indoor environment, and while they require attention in terms of humidity and temperature, they do not require a lot of space, food or (importantly) water. A single female black soldier fly produces about 900 grammes of larval protein, within three days. The eggs are laid on cardboard boxes in which water sources and organic food matter (this can also come from certain kinds of waste recycling) are present for the larvae to consume upon hatching. When the larvae reach the pupal stage, they are harvested by sifting through a pan system and then steamed, frozen or dried using a tunnel oven.

When Véronique and Gema first started their business from their kitchen tables four years ago, insect-based pet food was a pioneering niche market that was almost unknown to the general public. “Working with a new protein source was the only chance for a small brand like us to enter a pet food market oversaturated with hundreds of product lines, most of which were owned by a small number of big brands with a lot of resources”, says Véronique.

“They watched us small pioneers to see if the niche would become a trend.”

Véronique Glorieux, Eat small

Other small producers have established themselves since then too: Yora, founded by Tom Neish in the UK is an example. But now the big monopoly players in the pet food business, such as Nestlé (controls 30 percent of the US pet food market) and Mars (controls 41 per cent of the US pet food market), are getting on board as well. “They watched us small pioneers to see if the niche would become a trend”, Véronique explains. “Apparently yes, because now we see that everybody wants to have at least one product line with insects in it and take a part of what is seen as a market that will constantly grow within the next years.”

In Europe, this growth has been facilitated by 2017 changes in regulations affecting the use of insect protein in animal feed. It is also because the global pet food industry is a huge and lucrative market. In 2020 it was valued at 96.8 billion USD. Demand is set to rise as pet numbers increase, notably from established markets in the United States, Western Europe, Brazil and Japan; and with it a growing consumer interest in organic and more environmentally sustainable pet food as well as “livestock-free” diets for pets. In November 2020, Nestlé’s Purina brand piloted a dog food catchily named Beyond Nature’s Protein in Switzerland, but at present only one of their two flavour options contains any insect protein (12 per cent) and this is still mixed with 17 per cent meat protein. In March 2021, Mars announced the launch of their new black soldier fly-based cat food called Lovebug with 30 per cent insect protein.

Meanwhile, Eat Small has been growing too and attracting a steady stream of new canine fans. Their first production run of two tonnes for their premiere dried food line in 2018 took about two months to sell. Now they are shifting over ten tonnes every four months. In September 2019 Eat Small added a second line of dried food and a new line of wet food at the end of 2020. “Our community is growing by the month”, they say.

Shifting mass pet (and human food) systems completely to less harmful, more circular alternatives will take time but the burgeoning market in insect-based protein pet foods shows how quickly both market and production can adapt and grow from kitchen table ideas and determination.

Text by Sophie Lovell

Cover image by GinnPalme