For rural families in China whose worker generation is absent, the chair is a powerful tool for resilient, collective social and economic structures. Anthropologist architects Jingru (Cyan) Cheng and Chen Zhan bring chairs to The Common Table.

Ripple, Ripple, Rippling is a project about specific survival tactics of marginalised groups rooted in precarity. It was developed for the international Driving the Human exhibition of transdisciplinary, future-proof artistic prototypes. The project looks at China’s floating population — the 285 million people in China, mainly rural migrant workers, who are “floating” between their workplaces in the city and home villages in the countryside. The domestic result of their transitory economic lifestyle has led to the absence of a “middle generation” in more than eighty per cent of rural families in China. The grandparents and young children left behind live together in the villages, economically dependent on the middle generation working in the city. This dissolution of families is a survival tactic that fundamentally challenges the nuclear family model. What has emerged is an intergenerational, interdependent way of living that is somewhere between the family and the collective.

“Floating”, “dissolving” and “rippling” are ways in which these families form complex networks of care and support systems that go beyond the nuclear family structure. They hinge on dependency across generations and households. We believe there is much valuable and empowering knowledge embedded in the ways in which these families have created new forms of functioning domestic structures. Through a transdisciplinary investigation, which combines anthropology, architecture, performance, and filmmaking, our goal is to devise an experimental, collaborative method that is able to recognise, articulate, and communicate such knowledge.

Our starting point is an apparently simple article of furniture: the chair. The chair is the most common piece of furniture for rural Chinese families. It is also a spatial device that facilitates sitting — sitting down to eat; waiting for something, or someone; or playing cards by the side of the road. Although this act may seem mundane, it matters a great deal in China where one sits and for what. People tend to sit on and around spatial thresholds — that could be in their yard, at the gate or in front of the convenience store on the village street.

To an outsider, the sitting villagers may appear to be doing nothing more than having the occasional conversation with passing fellow villagers or neighbours. What they are actually doing is a form of active waiting, which enables them to be continuously attentive to others, anticipating negotiation, mediation and association. In other words, by pushing their own bodies to inhabit thresholds, these villagers are actively building up an elastic field of support and a sense of relatedness between themselves. This active waiting on a collective scale is fundamental to forming resilient assemblages of social and economic security that hinge on inter-generational and cross-household dependency, at the time when state welfare is insufficient and core family members are absent — and the chair is an essential tool for its practice.

For us, the chair becomes a symbolic embodiment of the ways of living in the village, where a rippling effect is forming through a liminal state of constant emerging, unfolding and becoming. This is in sharp contrast to the modern nuclear family construct with its fixed domains, clear boundaries and divisions of labour.

A dining table with chairs is one of the most common components at the symbolic heart of what many people call home. But “home” and “family” are not the clean-cut stereotypical models decision-makers tend to assume. So we thought to unsettle this setting with a cut-up assemblage piece we made for Driving the Human and called the Dinner Set. By making the familiar strange, we hope to trigger thoughts and imaginaries about alternative forms of family and domesticity. The installation was created by subdividing and reassembling four old wooden chairs, each one contributing its own past represented in the wood grains and washed out colours. It is the imperfection of the material and form that add depth to these found objects.

Although each divided piece of wood cannot stand on its own, once connected with other pieces they are able to hold themselves together again. This is, in fact, the same logic as the survival tactic practised by the dissolved households in rural China, relying on an intergenerational and interdependent way of living. What does it mean to be a family? How do we live together? How do we care for one another?

The Dinner Set is a materialised image of the idea of the dissolved household. But gathering together for a commensal meal not only symbolises the idea of the family in terms of traditional kinship structure, but in our project, it also symbolises the constant cycle of separation and reunion that contributes to family prosperity in China. It indicates a way of understanding human relatedness, in particular, the elastic form of association within Chinese society.

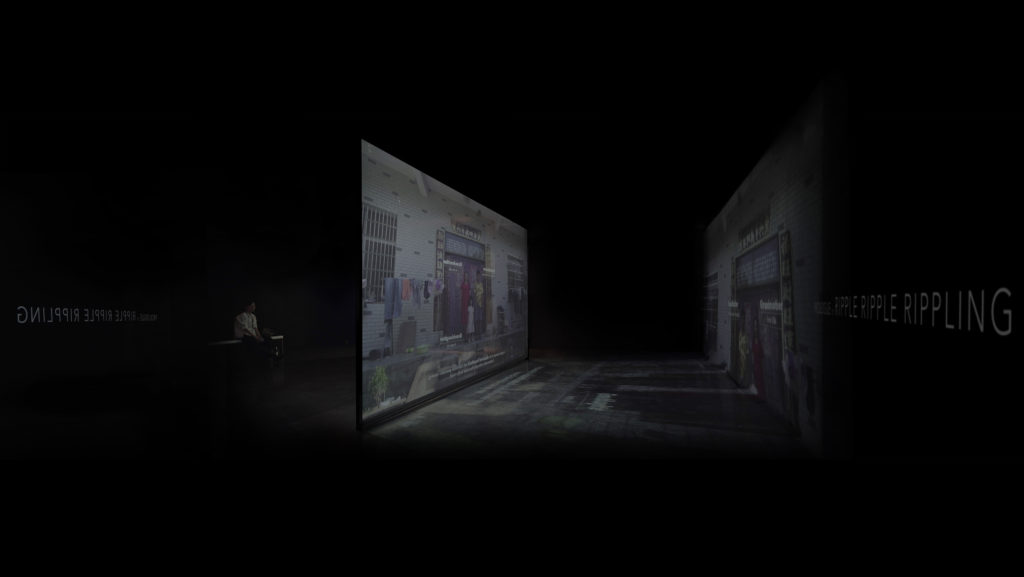

Ripple, Ripple, Rippling is planned to continue with a documentary-fiction filmmaking project in collaboration with theatre director and choreographer Mengfan Wang. Working closely with villagers in Shigushan, Wuhan, the intention is to create conditions in which villagers can become active agents of co-creation, forging a collective enunciation. The film will be simultaneously an ethnographic documentation; a hosting device of the villagers’ own performative expressions, storytelling, and imaginaries; and an acted manifesto through collective happenings in situ performed by the villagers themselves.

Jingru (Cyan) Cheng is a transdisciplinary design researcher, working on the intersections of architecture, anthropology and visual art. Cyan has exhibited at Critical Zones: Observatories for Earthly Politics (ZKM, 2020-21), Seoul Biennale of Architecture and Urbanism (2019), and Venice Architecture Biennale (2018), among others. Cyan co-leads an architectural design studio, ADS7, at the Royal College of Art, exploring the politics of the atmosphere. She holds a PhD in Design from the Architectural Association (AA) in London and was the co-director of AA Wuhan Visiting School (2015-17).

Chen Zhan is an architect, anthropologist and independent filmmaker. Chen’s film practice focuses on the socio-political struggles of the marginalised through the lens of the everyday. Her short documentary, Ahmad, tells the story of a Lebanese asylum seeker who rebuilds his life through cooking and food-sharing. The film debuted at the London International Documentary Festival (2019).

The would like to express a special debt of gratitude to the people of Shigushan village who have generously let them into their lives over the years for the making of this project.