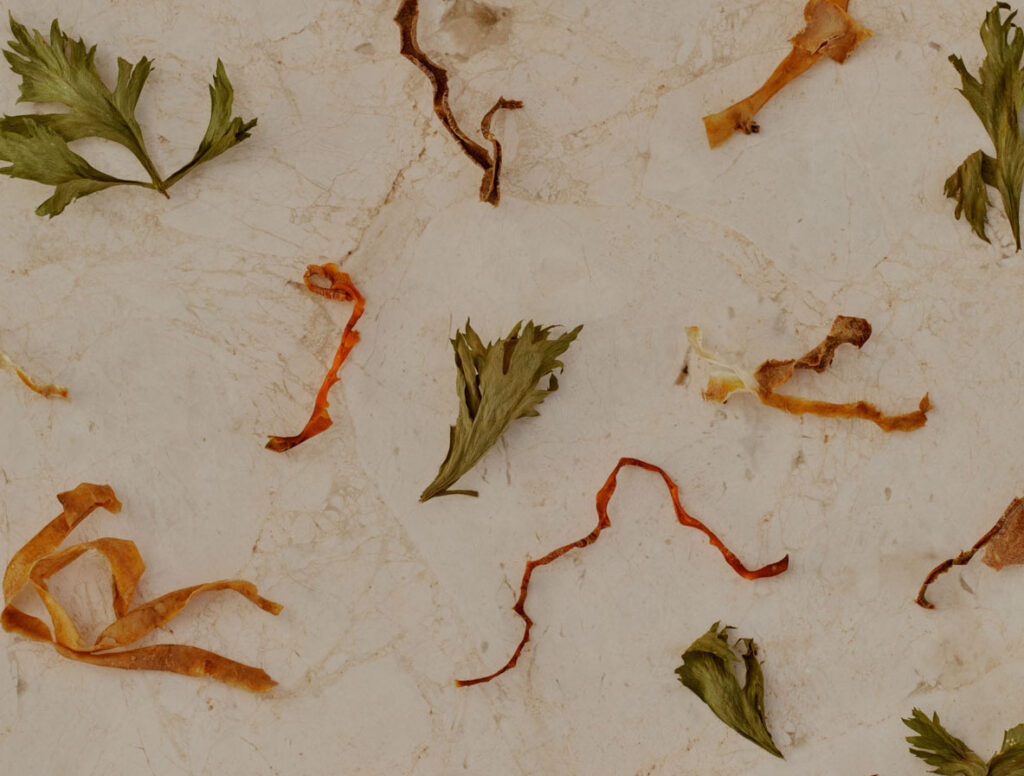

Understanding and addressing food waste is a collective process that goes beyond the kitchen. Writer and editor LinYee Yuan looks at some fine dining pioneers working to turn a distasteful subject into a revelatory and inspiring source to awaken both tastebuds and the imagination.

We have been grappling with food waste for as long as we have been storing food. Our prehistoric ancestors cured, brined, salted, and fermented their way through the ages in order to safely consume foods that would otherwise be long past their expiration dates.

But in this last century, with the rise of industrial agriculture and supermarket culture, our collective concern for using and preserving food has waned. Instead of making stocks, sauces, or stews with food scraps, these organic bits find their way to the nearest bin and, devastatingly, the landfill. In the United States alone, fifty-two billion tons of food from manufacturers, grocery stores, restaurants, and hotels end up in landfills annually, where the aerobic conditions emit huge amounts of methane gas and leachate, which poisons groundwater. In the United Kingdom, hotels account for an outsized share per person of food waste produced across the hospitality sector – seventy-nine thousand tonnes produced annually. Whether politics, supply chains, distribution systems, or aesthetics are to blame, our food waste problem is ultimately one of ethical concern – we could, in theory, feed all the world’s 815 million chronically hungry people by saving just one-quarter of global food waste.

We could, in theory, feed all the world’s 815 million chronically hungry people by saving just one-quarter of global food waste.

If hope is to be found, it may be in our stomachs. Our most joyful food memories are frequently built on austere practices handed down by generations of home cooks, often women, who layered flavours and underused ingredients to create culinary pleasures as diverse as biscotti, gumbo, or offal grilled over an open flame in the form of anticuchos in Peru or yakiniku in Japan. Unlike dishes typically associated with French haute cuisine or Korean royal cuisine, some of the world’s most celebrated fare has emerged from the alchemical practice of turning food waste into food treasure. Much of Italian food culture proudly derives from cucina povera, or peasant cooking, using day-old bread, fatty animal bits, cheese rinds, and vegetable offcuts to create complex flavours. What we know as the American South’s soul food is a melding of flavours that can be credited to innovative use of techniques and ingredients by enslaved African people.

The fine line between disgust and deliciousness will be the geography of the most exciting cuisine of the future. What flavours and new ways of nourishing ourselves might lie in wait at that shifting boundary? There are fond food memories entangled with the chewy “qq” of chicken feet, the creamy stink of casu marzu (the Sardinian delicacy of cheese transformed by the maggots of the skipper fly), and the ancient rush of freshly harvested spirulina. Culinary delights are often inherited treasures—what might be strange, invasive, or misunderstood for some, hold sensual pleasure for others. The joy of trying something new can be obstructed by cultural conditions that block the creation of new culinary imaginaries. Always say “yes” to new flavours, new gastronomic experiences, new ingredients, and new textures; open the door to new ways of tasting.

The wave of community fridges that have cropped up globally in response to the uncertainty fueled by the pandemic and food shortages illuminates ways that mutual aid, food recovery, and an evolved community consciousness can model new ways of relating to one another and to food. The task of navigating this uncharted path requires patience and an acceptance that our lives are interconnected through the food system. Our newfound relationship with the time-laden tasks of making sourdough, kimchi, kombucha, or home-brewed beverages might prompt us to consider how some of our most ancient unseen collaborators – moulds, bacteria, fungi – could unlock new ways of preserving, metabolizing, and tasting food.

The fine line between disgust and deliciousness will be the geography of the most exciting cuisine of the future.

The bridge to new culinary innovation is one that the hospitality industry is uniquely positioned to build. Each hotel is a highly designed world unto itself and the best ones serve as mediators of ideas and aesthetics of place. With food and beverage as an extension of these values, the kitchens and bars that comprise the beating heart of hospitality can become emissaries for new ways of relating to our food. Finding deliciousness in underutilised ingredients through processes at the intersection of fermentation and thrift can lead to the delight of new experiences, which in turn can be a trojan horse for transformation.

In 2015, the world of fine dining was challenged when one of its own broke ranks. Blue Hill, a world-renowned restaurant in New York with a sister location at the bucolic Stone Barns Center for Food and Agriculture, turned its city location into a two-week experiment delving into the possibilities of dumpster diving. Using culinary techniques typical of fine-dining establishments, chef Dan Barber and his team collaborated with local producers, distributors, restaurants, and retailers to divert ingredients like spent cheese rinds, vegetable peels, fish skins, and stale bread to create a menu of delicious delights.

The challenge to waste less in the most elite kitchens around the world was issued.

The pop-up, cleverly called WastED, called attention to “what chefs do every day on their menus: creating something delicious out of the ignored or un-coveted,” as per its website. Like those nonnas and unsung heroes of kitchens past, Blue Hill’s cadre of white-shoe chefs transformed perceived trash into treasure. Sending out dishes like a stew of kale ribs with pockmarked potatoes and parsnips; pasta trimmings with monkfish tripe, smoked fish head sauce, and cracklings; a juice pulp cheeseburger; and a charred pineapple core granita, the Blue Hill team delivered on their promise. The challenge to waste less in the most elite kitchens around the world was issued.

The year before Blue Hill made headlines, Douglas McMaster, a young upstart chef in Brighton, United Kingdom, opened the doors to Silo, arguably one of the world’s first zero-waste restaurants, which worked directly with farmers and suppliers to use hyper-seasonal products and cut out any single-use plastics from their supply chain. Coffee grounds were used to grow mushrooms, tableware was made from pressed plastic bags, local grains were milled, and butter was churned in-house. As partner Blair Hammond told Euro News, “Everything that comes through our door goes back as compost.” McMaster and his team found ways to close the loop with the ingredients and the organic “waste” the restaurant produced by returning it to the farmers as black gold. At the restaurant’s current iteration in London, McMaster has taken a similar approach by slowly building a network of purveyors in and around a city that is not typically associated with food production to supply his restaurant with the freshest and most sustainable ingredients.

The ultimate luxury is that of time and care, and what better way to indulge in that luxury than with the act of fermentation?

In 2017 McMaster helped open the now-shuttered CUB, a closed-loop concept bar and restaurant in London helmed by the celebrated bartender Ryan Chetiyawardana. Offering a menu that seamlessly moved between food and drink courses, the restaurant not only upcycled ingredients but also sought to “reduce, and crucially re-assess,” Chetiyawardana told Eater, the idea that “luxury needed to be opulent…to elevate the exotic, and only focus on the finest cuts.” When Chetiyawardana opened his first bar, White Lyan, in London in 2013, it was the first cocktail bar in the world to use no perishables—no fruit, no ice.

Eschewing some of the more common markers of sustainability in the hospitality industry as limiting in their approach, Chetiyawardana’s Lyan group of cocktail bars has leaned on the ancient-future technologies of food preservation, working with the likes of Dr Arielle Johnson and Dr Johnny Drain, both specialists in the art of flavour through fermentation. For Chetiyawardana, the ultimate luxury is that of time and care, and what better way to indulge in that luxury than with the act of fermentation? Whether using lemon peels to create falernum syrups, used grounds for coffee oils, or tea bags for tannin tinctures, the respect with which Chetiyawardana treats each ingredient and process reflects his philosophy. Even waste citrus husks are transformed into cocktail coasters at his bar Lyanness, creating a physical foundation for storytelling with each drink served.

A weed is a plant out of place. As we face existential uncertainty in the face of rapid human-caused climate change, this simple adage has taken on a more urgent meaning.

Time and care are also the primary drivers for Native, an award-winning cocktail bar in Singapore focusing on flavours unique to the confluence of cultures that make up the island city-state. With foraged and sourced local ingredients like weaver ants, jackfruit, pink jasmine, turmeric leaves, and wild curry leaves, bartender Vijay Mudaliar uses cocktails as a medium for charting the geography of place. As he told the Michelin Guide, “What grows together, goes together,” and his diverse offering of local spirits like Arrack, made from coconut flower sap, paired with regional ingredients, reflects that ethos. By preserving flavour through infusing, brining, curing, and sugaring – all processes familiar to our ancestors – Mudaliar’s drinks tell a story about the beauty of reciprocity and intimacy, taking only what one needs, leading with respect, honouring complexity, and knowing the provenance of an ingredient.

A weed is a plant out of place. As we face existential uncertainty in the face of rapid human-caused climate change, this simple adage has taken on a more urgent meaning. It offers a mirror to our skewed perceptions; a testament to our failed attempt at controlling the unwieldy, breathing, environment; and a glimpse of hope situated in the task of reorienting ourselves. In a time where we are facing the overwhelming effects of our toxic relationship with what we have long considered “trash”, it’s time to think about waste as the primary material for building our collective future.

LinYee Yuan is and design journalist and the founder and editor of MOLD, a critically acclaimed digital and print magazine dedicated to exploring how design and innovation can create food solutions for an expanding global population. Based in New York, she is currently an adjunct professor at Parsons, The New School, and was previously the entrepreneur-in-residence for QZ.com. She has edited and written for numerous publications, including T: The New York Times Style Magazine, Food52, Cool Hunting, and Elle Decor.

This essay was first published in 2022 in the book Taste and Place, conceived and edited by The Common Table founders studio_lovell for Design Hotels. A food book with a difference, it looks at ecosystems of hospitality through the lens of food to better understand the bigger system changes possible and necessary in order to transition to a low-carbon future. Text and images reproduced by kind permission.

Title and all images © Marina Denisova; reproduced courtesy of Design Hotels Ltd.