Merve Bedir is an architect and researcher who has developed a collaborative research, design, and action project “vocabulary of hospitality”, particularly with respect to borders, migration and refugees. As a former citizen of Turkey and an emigrant based in various countries for over a decade, she has a personal as well as academic investment in this topic which encompasses community, belonging, hospitality, the kitchen and food. Here she talks about kitchen-based processes as tools for collective belonging through a shared space on the Turkish-Syrian border.

Mutfak مطبخ, The Kitchen, is a space set up by our women’s collective that I belong to in Gaziantep, a Turkish city on the border with Syria. As a collective, our main principles are solidarity, horizontality and sharing, where the perception/role of the refugee in society possibly transforms from that of the guest to the host. We are interested in the architecture of hospitality in the kitchen as well as in relation to social connections and food. مطبخ Mutfak Workshop [mutabikh and mutfak are respectively the Arabic and Turkish words for kitchen] is an initiative by several women whom I encountered during my ongoing Vocabulary of Hospitality project, which included an exhibition of the same name in Istanbul in 2014.

Today in Turkey, less than a quarter of refugees live in camps, where they are provided with state services. The other three quarters end up in cities where they get very little help from the state and aid organisations. Unless they obtain legal status, refugees are not allowed to work and they are mostly unable to benefit from the health and education services of the state in which they are seeking asylum.

This communal kitchen was set up as an active attempt to learn to live together with an emphasis on solidarity, both in terms of finding a sense of belonging and identity to the city we live in and also to deal with the politics of nationalism and racism in Turkey. The project has a lot to do with the results of migration, especially the influx of migrants from Syria to Turkey since 2011, but is also about understanding the meaning of “living together” in a general sense. With living together comes solidarity, and sharing and the idea of collective belonging.

With living together comes solidarity, and sharing and the idea of collective belonging.

Mutfak مطبخ Workshop didn’t start off as a concept centred on a physical space in which to cook and eat. It began with the idea of coming up with ideas and solutions to the question of how to live together. One of the first projects we organised in Gaziantep, for instance, was a presentation and performance event based around the music of the region, with the intention of exploring a shared knowledge and culture. We have also organised walks within the city, as well as a variety of ongoing workshops on women’s rights in Turkey, violence against women in public space, violence at home, self-defence, and all sorts of things that women share. So Mutfak مطبخ is based not necessarily on a particular imposed identity, but rather on issues or pleasures that are shared by all, together.

The Kitchen was started in an immigrant neighbourhood in Gaziantep in a historical building maintained by a cultural NGO called Kırkayak. From the beginning, it was not just a place to cook, but to discuss what was needed, what we could organise amongst ourselves and lending solidarity: preparing and providing food, making a space for those in need of a bed for the night. Simple things, mundane things. From there it evolved to the idea of learning to live together, particularly because of the developing dominant discourse and language on polarization and segregation. The notion of living together was not only because we wanted to live together around the kitchen or Gaziantep, it is also a continuous and active assertion, an emphasis to put forward our position for a certain future of being together.

What are the elements of the Turkish kitchen? One of them is the traditional floor table, sofra, which is elevated around 30cm from the floor. People sit around it on the floor and eat together from shared platters. The onset of modernity in Turkey meant leaving the floor table behind. I remember very clearly from my own childhood this sense that you were almost considered uncivilised unless you ate at a high table rather than more communally at a floor table. It was even a source of embarrassment. But in the 2000s another kind of elite emerged, promoting a return to sitting around the floor table as part of a general return to tradition to the true identity of the society. It was about taking ownership of traditional culture, but this time from a religious standpoint. So, one of the things we did at Mutfak مطبخ was to consider the meanings surrounding the floor table and to dismantle and relearn it, to reproduce and relive it in a way.

The idea of learning together is brought forward also with the idea of “cityzenship” (citizenship with a Y, emphasizing a belonging to the city rather than the nation-state). In Turkey, there is an article of the Municipality Law (1938), which states that people who live in the same city belong to the city and have a direct say in the decision-making process in the city. The word for this in Turkish is hemşehri, it is the same word in Arabic and Persian as well. We took this idea of proximity and the idea of participation around a table as a connection to this idea of cityzenship (with a Y). Being around the same table can be related to the architecture of intervals and to the theory of intervals from Ulus Baker and at the same time to the Municipality Law that promotes the idea of belonging to the city.

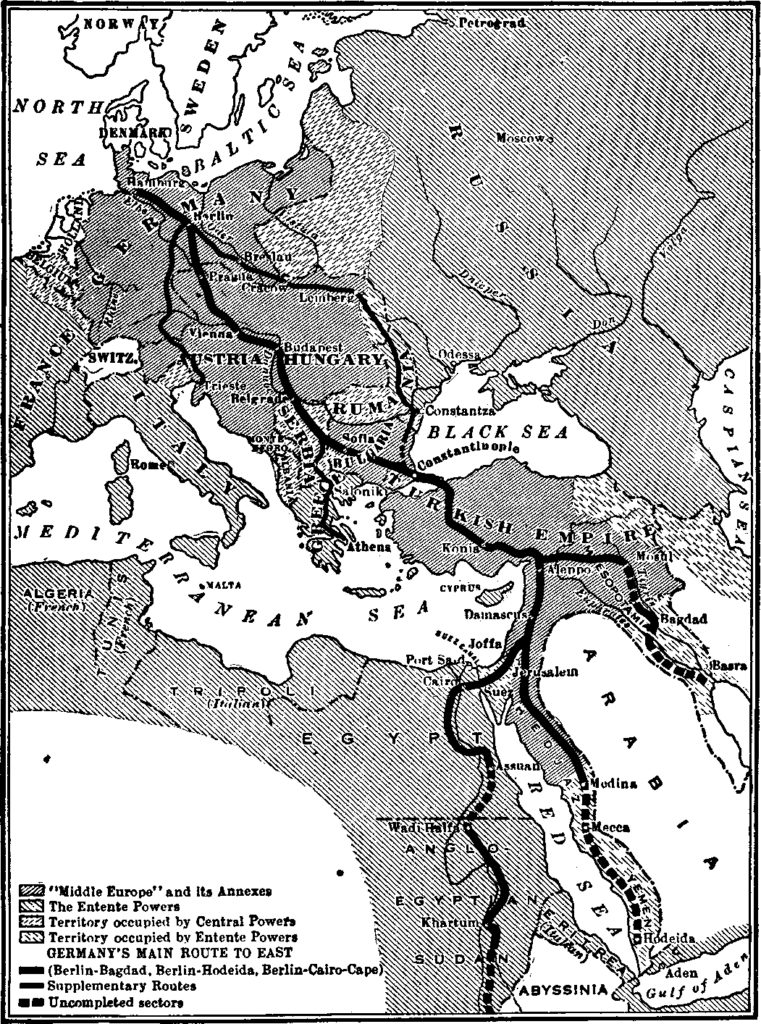

From the landscape of the kitchen, we can look further to the landscape of the region. The idea of citizenship in this case is an interesting one. On this pre-WWI map we see a train line between the German Empire and the Ottoman Empire to connect Berlin and Baghdad, going through present-day Turkey. This train line also just touched the southern edge of Gaziantep on its route. But things got complicated at the turn of the century and although the train line was built around Gaziantep, it was also dismantled shortly afterwards. Where it used to run is today more or less the border between Turkey and Syria. Before the train line was built, Gaziantep was part of the region of Aleppo.

Now there is a wall along this border. To the south of it near Gaziantep are groves of olive trees, to the North, on the Turkish side are none, in fact there is a minefield. The olive trees in this landscape are actually the defining boundary across the region, a region that is difficult in some ways to define: it’s Mesopotamia and the Levantine, but it is also Turkey and Syria. One image that has become symbolic of this region since 2011 is the one of refugees walking through the olive trees to get to Turkey. And this image is complemented by images of undocumented, seasonal, migrant agricultural labour that is an ongoing and existing phenomenon in the Turkish economy in general.

On either side of the border, the differences in management of the landscape are clearly visible, but olive cultivation still continues to be part of the livelihoods of the people. However in Turkey, the practice is modernised, mechanised and confined to particular types of olives and groves. For instance, in 1990s the state development agency in Turkey started giving incentives to grapes and wine instead of olive farming. This caused other kinds of migration, other ways of pushing towards a certain kind of living, a certain kind of economy, a certain kind of knowledge and a certain kind of societal structure. In the 2000s, the state started to give incentives to a type of olive, which then dominated the cities in the East. What I mean to say here is that the management of landscape and the management of people somehow follow a similar ideology, people and landscapes share the same fate.

Olives define a region of belonging, both geographically and culturally, rather than a national one.

But in essence, olives define a region of belonging, both geographically and culturally, rather than a national one. Olive cultivation is a family practice, done by the same families for centuries. They make products from the olives such as herbal medicine, soap, olive oil, and so on. A couple of years ago, the remains of a Bronze Age settlement called Oylumhöyük was found very close to Gaziantep. Olive-grinding spaces have been excavated there and in the gravesites, olive seeds, as well as olive oil pots, were found buried together with the people. Olive products were used there then too for healing, medicine, textiles and fuel. The olive trees and the management of the landscape, the economy, the livelihood of people, families and ancestral knowledge, are all things that we have looked into in the Kitchen Workshop. This was made into an episode of The Critical Cooking Show at the Istanbul Design Biennale 2020-21.

Another project at the kitchen revolves around a popular 13th-century cookery book in Aleppo Library, called the Kittäbu’t-Tabbâhîn. A new translation of which, was recently published as Scents and Flavors by NYU Press. The cookbook contains 635 very elegant Abbasid palace recipes, but it is not unique, there are various original copies of it still in existence. The reason for reproducing the cookbook back then was to share these aspirational recipes, a practice that has evolved through the ages ever since. Through sharing, this cookbook has come to represent the empire in a way, representing the culture of a certain elite, a certain group of people. Taking the Aleppo cookbook as a starting point, we asked each other whether we had cookbooks at home or just learned from our mothers, in a sharing way. In that sense, how would we write these recipes today and how does a recipe itself grow, evolve and change as it is passed on. If you look at our Instagram page, you will see a lot of these recipes cooked by us.

Since we started the Mutfak مطبخ (Kitchen) Workshop in 2015, all of our activities there have been a way of relearning, of taking ownership of the kitchen but also letting it go, dismantling it and making it into a space of participation and collective belonging for people from a region that has millennia of geographical, cultural, and political intersections.

Merve Bedir is an architect and researcher. She is the co-founder of L+CC and Aformal Academy: Re-learning the City program between Shenzhen and Hong Kong (Pearl River Delta region). Since 2013, part of her work has focused on migration and refugees. She curated an exhibition on migration, mobility, and urban space in Istanbul, named Vocabulary of Hospitality. She is a founding member of the Centre for Spatial Justice in Istanbul and Mutfak مطبخ (Kitchen) Workshop. Her work has extended towards communities and landscapes, human and nonhuman relationships since she moved to Pearl River Delta region, where she also worked as an associate curator in Design Trust, as well as an adjunct assistant professor at Hong Kong University. Merve Bedir holds a PhD from the Delft University of Technology, Faculty of Architecture and Bachelor degree from the Middle East Technical University in Ankara.