Braai is an Afrikaans word used to describe the social activity of grilling meat – lots of it – over a wood or coal fire. But this highly popular South African version of the barbecue is also at the centre of a quest to make this pastime a symbol of national identity. The Common Table talked to Duane Jethro, an expert on heritage formation and nation-building in post-apartheid South Africa about braai culture, designated tong bearers, settler-colonialism and stereotypes of savagery.

Sophie & Orlando Lovell: You are researching at the Centre for Curating the Archive at the University of Cape Town in South Africa, where you work on the cultural construction of heritage and contested public cultures. Can you explain what that means in practice?

Duane Jethro: I work on the languages, especially the cultural languages, that are employed for the making of new heritage, as well as the public cultural contestations that heritage debates often stoke. The most common example I can give for such contestations is the debates about whether or not statues dedicated to officials and figures that are considered to be dubious or problematic and racist should be removed.

How does that connect to your interest in South African food culture?

It relates to a book project that arose out of my PhD dissertation on heritage formation and nation-building in post-apartheid South Africa. In my book, Heritage Formation and Consensus in Post-Apartheid South Africa: Aesthetics of Power, I looked at five case studies of new heritage projects initiated in the post-apartheid era that were meant to be specifically nation-building in scope, focus and purpose. I specifically looked at the attempted renaming of National Heritage Day as National Braai Day, and the curious project of trying to transform and install what is a common food culture and pastime in South Africa known as braai.

That’s where my interest in South African food culture comes from: the way food culture intersects with heritage. What is distinctively South African about a food culture? That was the question that sat in my mind.

It’s an everyman’s food culture and pastime.

So in your book, you take the use of braai culture – what we would probably call barbecue culture as an example of heritage-building. Why braai?

Why braai? I like to braai! But also, I think braai is an interesting food culture practised in South Africa because it’s not high culture. It’s not thought of as an esteemed traditional cuisine that often gets to claim the decorations of a national food culture that we see in the French gastronomic tradition for example. It’s an everyman’s food culture and pastime.

Does it really cut across ethnicity, race and class the way some people claim?

It’s interesting to see the kind of claim-making that circulated around this everyday pastime. In essence, the problem that a food culture like braai poses is: how is it possible to claim the national significance of an everyman’s food culture and pastime that is celebrated and claimed nationally all over the world at the same time?

That was an interesting problem and it opened a way for me to track the different claims that were being made for and against braai as being distinctly South African, made by a range of stakeholders: politicians, entrepreneurs, retailers and the whole confluence of interests that intersected around what appears to be this kind of national awakening to a food culture we apparently all share.

It is based on this idea that in South Africa, everyone gets around the fire and we have a chat, and we can leave the politics outside of the barbecue because here is a space in which we can come together.

Does the attraction to braai as a positive symbol come from the thinking that represents a relatively safe space in a country that has suffered a great deal from huge conflicts, disparities and injustices?

It is based on this idea that everyone braais in South Africa, everyone gets around the fire and we have a chat, and we can leave the politics outside of the barbecue because here is a space in which we can come together. Intuitively this idea made sense in the post-apartheid South African dispensation, at a particular moment. And it made sense in part through the various rationales that were deployed by the different stakeholders involved. Does it really cut across ethnicity, race and class, as some would claim? Yes. Braai is popular among all race groups in South Africa. But braai means different things in all of these different groups and classes, it doesn’t do the same thing for everybody. Some people use an open-fire cooking method for subsistence cooking on a daily basis; they don’t call that a braai. A braai is effectively a fire you make in your leisure time for special foods that you buy with surplus income. It’s not everyday food. It’s reserved for special days, special occasions when you have surplus money to spend on it.

Did you come across anything in your research relating to the origin of the word “braai”? Because it has its own distinct word in contrast to other open fire cooking traditions such as barbecue, for example – was that an opportunity for it to be labelled as a national culture?

That’s a great question. One of the things I address in my book is the role of Desmond Tutu in establishing braai as a national pastime that we should practice on Heritage Day especially. He made the point that we have 11 official languages in South Africa, but braai is the one word that we use across all these languages. In some ways it is shared, it’s a young Afrikaans word that goes back to the late 19th century, it has roots in the Dutch word braden. But we also have other words for open fire cooking and the sociality that goes along with that. Shisa nyama for example is another term that is often used for a gathering of people around open fires for barbecuing and hanging out, that’s also often used.

And what is the origin of shisa nyama?

It’s a Zulu word literally meaning “burnt meat”, referring to the way that food is cooked over coals. Both braai and shisa nyama are interesting because, and I guess this travels through all other terms for barbecue, it’s not just a description of a cooking method, it also speaks to the social aspect that goes with it. In South Africa we’ll say, we’re gonna have a braai, and immediately you know it means a social occasion, with people coming over. It’s a hangout, it’s not like a private dinner.

So are you saying there really isn’t much difference between a South African braai and an Australian or British or American barbecue except in the name – and perhaps the types of meat that are cooked?

These traditions of open fire cooking share many similarities. There are definitely associations with a middle-class pastime associated with domesticity, or social pastimes of growing up in a leisure culture. But in these different places, there are different cultural resonances and associations that attach. It’s not just a matter of etymology. The main entrepreneur that I tracked in my book, Jan Scannell – an accountant who ultimately went on to adopt a media persona built up around braai – argued that some of the oldest [hominid] paleontological remains indicate that the first controlled open fire cooking happened here in South Africa. So, in a strange way, as validated by scientific evidence provided by the journal Nature, South Africa could lay claim to the first barbecues ever – however tenuous it may be.

That’s the interesting thing that braai does so well: concealing the layers of politics that are encoded within it.

Is this the guy who changed his name to Jan Braai and proposed changing South Africa’s National Heritage Day to National Braai Day about 15 years ago?

Yes, and he can be associated with the debates we have had in South Africa about the significance of braai as a national pastime. I think it’s been widely accepted as such – its significance however is up for debate. But it was mainly through his public relations project, which was strongly orientated towards nation-building and reconciliation, that the cultural significance of braai was elevated. So in 2005 he started a campaign to get South Africans to braai on Heritage Day, which occurs on the 25th of September each year. There’s no official, politically prescribed way of celebrating Heritage Day. It was into this cultural and political vacuum that he stepped with the public relations project that is ultimately very innocuous and very common-sensical: let’s do something that we really enjoy together and in that way, we can be patriotic and proud of who we are as the South African nation.

It is also not a tradition that’s as compromised as for example turkey on Thanksgiving in the US…

Yeah, barbecue and braai and these open fire cooking methods are very fascinating because they kind of smoke out their historical traditions and origins – it’s very immediate and very innocuous. Who doesn’t want to be with their friends around a barbecue and enjoying themselves? There’s no politics to that…

Unless you’re vegan!

Unless you’re vegan, amongst other things. But that’s the interesting thing that braai does so well: concealing the layers of politics that are encoded within it. Jan Braai was very much invested in promoting and advocating one version of it as a unifying national heritage pastime. And at the same time concealing the various layers of politics that were associated with this food way at the same time.

“As it is understood today, and as it has been understood for centuries in the west, barbecue evokes a stereotype of savagery that has nothing to do with native culture and everything to do with white European culture.”

Andrew Warnes

That leads me to the next question, which relates to your recommendation in our pre-talk that we read Savage Barbecue by the Australian author Andrew Warnes. There was a statement he made in it that really caught me: “From the era of conquest onwards, barbecue arose less from native practices than from a European gaze that wanted to associate those practices with pre-existing ideas of savagery and innocence.” Would you agree with his view?

Andrew Warnes’ book is fascinating., it’s about the cultural construction of barbecue in the US. If I remember correctly, it starts out with this account of the restaurant at the National Museum of the American Indian [Washington D.C.], and he tells this convoluted story about why barbecue is associated with Native American tradition, regionally and historically, and yet the museum doesn’t serve this cuisine in its cafeteria. Why is that? What’s going on there? It doesn’t make sense. But the way he unpacks it is that, ultimately, barbecue is an etymology that goes back to the 18th century, and this etymology is associated with European visions of indigenous peoples, specifically in the Caribbean at first but later on the continent. My favourite sentence from his book is from the introduction, from which you get the spiciness of his interpretation: “As it is understood today, and as it has been understood for centuries in the west, barbecue evokes a stereotype of savagery that has nothing to do with native culture and everything to do with white European culture.” So it’s about the necessity of manufacturing an image and associating a food way with an indigenous people for entrenching a settler-colonial enterprise – you need to set that up in order to validate and legitimate your sense of dominance. But then you still retain the indigenous associations behind it. So only once a food way is domesticated, can it fully make sense as something that is worth celebrating.

It’s this hyper-masculinised sense of conquest, sense of control of an element like fire, of being outdoors, that touches on a sense of masculinity associated with the settler-colonial enterprise.

Did you see parallels there with braai?

I found his book quite useful in thinking about braai and barbecue as an invented tradition that very definitely has roots and associations in and with the settler-colonial project. And you see these resonances in many of the dominant features of the contemporary middle-class practice of barbecue today. On the same page from which that quote comes, he quotes another author saying, “The barbecue elegantly embraces several stereotypically ‘guy’ things: fire-building, beast-slaughtering, fiddling with grubby mechanical objects, expensive gear fetishes, beer-drinking and, of course, great, great heaps of greasy meat at the end of the day.” So it’s this hyper-masculinised sense of conquest, sense of control of an element like fire, of being outdoors – all of that stuff – that touches on a sense of masculinity associated with the settler-colonial enterprise.

What role do you think food, and specifically barbecue and braai, can play in decolonisation?

For whites during the 1970s, braai became an idiom for wealth and leisure culture, captured in an automobile advert that aired widely on South African radio. The jingle for this advertisement went: “We love braaivleis, rugby, sunny skies and Chevrolet”. Braaivleis is braai meat, which is no mere barbecue. Braai is a profound cultural ritual recalling the days when Afrikaner pioneers rode the empty plains on horseback and brought down buck with a single shot. They built a fire and roasted the meat right there in the open, beneath the sunlit blue heavens. Celebrated in the opening lines of the old national anthem.

So barbecue, braai, is rooted in these kinds of associations, settler-colonial projects of pioneering men. How do you decolonise that? I think you can feminise barbecue and take the meat off the table – have vegan and vegetarian barbecues. My associations with braai were deeply established, so when I came to Europe for the first time and saw how people were barbecuing I was like, y’all are transgressing the rules of how to do this!

In what way?

Like vegetables are often an accompaniment to the main dish of meat that is cooked on the fire, so when people would bring in vegetarian or vegan sausages I was like, That doesn’t make sense to me entirely, but ok, go ahead! And with that, you have to have an apartheid-style separation on the fire [laughs].

Two grills, one for the vegetarian and vegans, one for the meat-eaters?

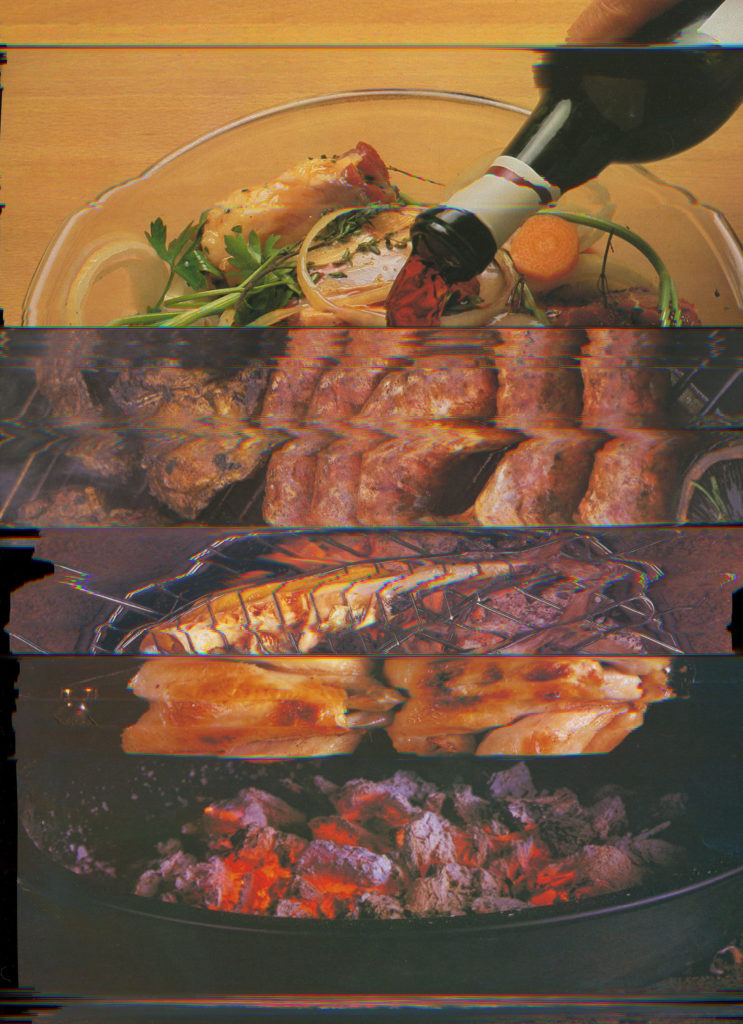

Yeah, there must be no contact. Also another thing about braai that’s different from European grill culture is that we wait until everything is cooked before sitting down to eat. The meat is cooked in the order that the designated braai master decides is best, according to the heat of the fire. So a cooler fire for chicken, a hotter fire for red meat like steak. This will all be cooked and put together in a special bowl called a braai bak to keep warm on the side until everything has been cooked and all the salads have been prepared. Then everyone will go to the table and all the food is dished out.

It’s interesting what you said about feminising braai. Barbecuing is often like role-playing, certainly from the European perspective that we have grown up with: the guys outside vying for who’s going to be the one to make the fire, then one of them ending up being grillmeister. We even joke about the guys battling it out over who gets the tongs. It’s somehow this moment in which we’re allowed to role-play, or we allow it. But in many cases, barbecuing really is still a male-dominated activity that hasn’t been reclaimed by women.

It is fascinating. In the domestic space of the home, it’s the women who cook. But the moment you step outdoors onto the porch, the men have to seize control of the cooking operations. What’s also interesting about your observation is that it suggests that these things are also constructed universally in different places.

We should try and think of ways of feminising barbecue, having women leading the way and seizing the tongs.

Those gender associations are actively constructed as one of the important features and aspects of braai, of reinforcing normative roles around domestic food consumption, of reinforcing those structures of gender division around the fire. So yeah, we should try and think of ways of feminising barbecue, having women leading the way and seizing the tongs, and sending the men into the kitchen to prepare the salad and prepare the table. And to introduce new ingredients and new ways of celebrating barbecue that go beyond just meat.

Then there is the whole aspect of cooking with wood and coal not being very good for the environment, and discussions about alternative heat sources versus flavour. Or the fact that if you ritualise something enough that eventually, over time it moves away from its origins into a symbolic space. But perhaps that might be a good thought to end on: the future of open fire cooking and how to feminise it.

Yeah, feminising barbecue in 2021, it’s going to make me think.

Duane Jethro is currently a junior research fellow at the Centre for Creating the Archive at the University of Cape Town, where he works on the cultural construction of heritage and contested public cultures. He is the author of Heritage Formation and Consensus in Post-Apartheid South Africa: Aesthetics of Power, pub. Routledge, 2020 and he likes to braai.

Title image: “Braai or Die Trying” especially made for us by Nico Krijno, 2021