Food connects through time, cultures, community and adversity. A conversation with cookery writer and cultural anthropologist Claudia Roden about discovering identity and collective belonging through food – and writing cookery books.

Sophie & Orlando Lovell: Welcome to The Common Table! It is a real pleasure to have you with us. Your cookery books, in particular A Book of Middle Eastern Food and Mediterranean Cookery, were such an influence on the cooking and cuisine of the Lovell household from the 1970s onwards and continue to be go-to recipe sources in our library today – three generations! Tell us how food came to be such a passion and a calling in your life. How did your career in food begin?

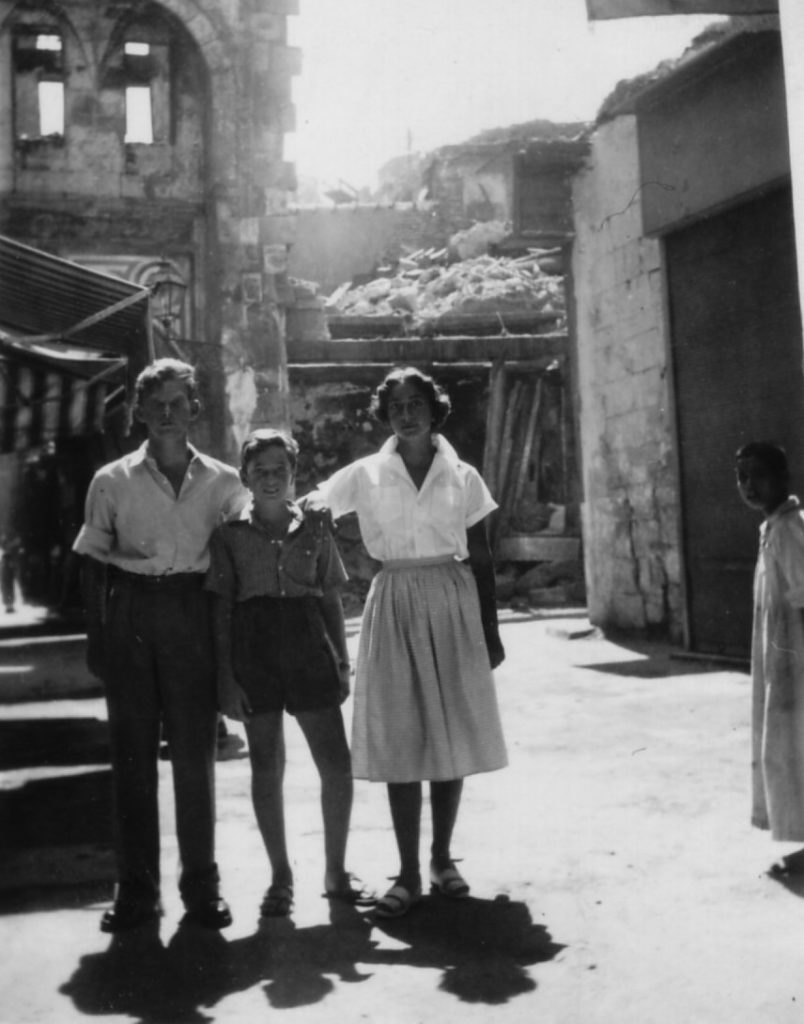

Claudia Roden: I was born into a Jewish family in Cairo in 1936. At that time, Egypt was very cosmopolitan, with many communities, and many minorities, each of them with their own cuisine. Even the Jews were a mosaic of cultures, my grandparents on my father’s side, for example, originally came from Aleppo in Syria. My father was conceived in Syria and born in Egypt and the family continued with their Syrian cuisine when they moved there.

On the other side of the family, my maternal grandmother came from Istanbul. The Jewish cuisine of Istanbul was very Spanish. Many of the Jews there brought it with them when they were expelled by the Alhambra Decree in the 15th century. In my grandmother’s time, the community still spoke a medieval Judaeo-Spanish between themselves, they had kept it up for over 500 years.

My father’s family and my maternal grandfather were merchants from Aleppo. They came from a long line of Arab Jews in Syria who traded along the big camel caravan trade routes of the East when Aleppo was the hub before goods were put on ships stopping at ports around the Mediterranean. When the Suez Canal was built in 1869, it ended that trade and Egypt took its place and became the most important mercantile country around the Mediterranean. That is why my family moved to Egypt along with a huge number of families from countries around the sea.

But there were no cookery books?

No cookery books. When I was young in Egypt, I never saw a cookery book or even a printed recipe. Recipes were handed down in families through the generations. Their cuisine was their identity. Every community kept to theirs. My mother taught our cook, Awad, to cook our family dishes.

When I was young in Egypt, I never saw a cookery book or even a printed recipe. Recipes were handed down in families through the generations.

Tell us how you came to write A Book of Middle Eastern Food, an absolute landmark and one of the great cookery book classics, first published in 1968 and still in print today, I believe.

In 1952, at the age of 15, I was sent to a boarding school in Paris for three years to do my Baccalaureat. After that, I went to London to study art at St. Martin’s School of Art. I shared a flat with my brothers and started cooking for the first time. I was there two years before the Suez Crisis happened. President Gamel Abdel Nasser nationalised the canal which had been under French and British control until then. He had already nationalised a lot of companies in Egypt, including companies belonging to Jews, to Christians and Muslims. France and Britain decided to attack and asked Israel to help. So the French, the English and Jews were all thrown out of Egypt by Nasser more or less all in one go. It was a big shock that suddenly within two weeks, my parents arrived in the UK along with a huge number of other refugees. I had to leave art school and get a job. I worked for the Italian airline Alitalia for a while because I could speak a lot of languages, including Italian.

It was a big shock that suddenly within two weeks, my parents arrived in the UK along with a huge number of other refugees.

For about ten years we all lived in a bubble of Jewish refugees from Egypt. I began collecting recipes beginning with my old community which included families from Syria, Turkey, Greece, North Africa, Iraq and Iran. Many had never been in print before because they had only been passed down orally in families. In the beginning, my interest came from the feeling that the one thing that we had, that we could take with us, was our food. Our cuisine gives us pleasure. It gives us happiness and it also reminds us of who we are.

Did those 10 years of recipe collecting feel like an education to you? Did it broaden your knowledge and understanding of who you were and your place in the world?

Yes, exactly. Until then I was very Europeanised like many of my generation in Egypt. At home in Cairo, we spoke French as well as Italian, we knew Judaeo-Spanish, and Arabic, and I went to an English school where we never learned anything about Egypt. We didn’t know the history of the country we were living in but we knew all about the history of England and we could sing all the Christian hymns.

It was the love of the food and a fascination with that lost world that made me research the history and culture of the Middle East with a special determination and passion. It was about who we were.

But after we left, I suddenly realised that I had lost my father’s Arab culture that I had somewhat rejected while it was all around me in my extended family. It was the love of the food and a fascination with that lost world that made me research the history and culture of the Middle East with a special determination and passion. It was about who we were.

At first, we tried to find cookbooks in Arabic about Arab food. We phoned our Muslim friends in Egypt saying, “Can you send us any cookbooks?” And the only one we got sent in Arabic was a cheap paperback translation of a NAAFI cookbook of the British military catering corps from the II World War. It was full of things like cauliflower cheese and jam roly-poly. Not a single Arab recipe!

Did your family support your work?

All my parents wanted for me was to marry. They started putting pressure on me with ‘proposals’ from the age of fifteen. Studying at university was out of the question, though art was acceptable. I married soon after they arrived and was happy with my role as wife and mother, to be a nurturer and what my father called “the sunshine of the family”. My parents were happy for me to collect recipes especially as I started with my father’s extended family. They didn’t see it as work, it was recording our heritage for us. In London, my mother had become a passionate cook and I spent a lot of time in the kitchen with her, helping and taking notes. And my father was thrilled with every recipe I got from a relative or friend. They were very proud when my first book came out.

Not having an academic education, I had a thirst for knowledge. Having no luck with books from back home, I went to the British Library and asked for any books they had on Arab cuisine. The librarian said, “Come tomorrow and I’ll have a list for you.” When I went back, all he had was a list of culinary manuals from the 13th century: 13th century Baghdad, 13th century Damascus, and 13th century Al-Andalus in Spain – all in Arabic. But I was thrilled to find an English translation by Professor A.J. Arberry from the 1930s of the 13th-century manuscript found in Baghdad, complemented by stories and poems of the time, as well as a description and sociological study in French of the manuscript found in Damascus by a French Orientalist called Maxime Rodinson (it has since been translated into English in the series Petits Propos Culinaires).

Rodinson had been in the French army stationed in Syria when WWII started, and they had had to stay there because the Germans had occupied France. He had been studying Arabic and sociology before the army and wanted to do his PhD so he went to a library in Damascus and found an ancient cookbook. He used the recipes to understand and describe the society of the time. That, for me, was a huge inspiration. I was absolutely enthralled, especially when I realised that some of the recipes were exactly like recipes I had collected from my own family who had come from Syria. Suddenly there was this thread, a connection through time and what we ate that was going back to 13th-century Syria and also to Baghdad. It was a fantastic confirmation of who we were and that we went back a long way.

Suddenly there was this thread, a connection through time and what we ate that was going back to 13th century Syria and also to Baghdad.

This connection to the past, and finding the reasons why this cuisine developed, gave me an excuse to take some time off from the little ones, get someone to babysit, and go to the British Library and other libraries, to read and read and read about the history of the Middle East that I never knew. So, I just taught myself.

That must have taken a huge amount of dedication and willpower on your part. And what you were doing was entirely new ground in a modern context…

Soon after my first book came out, a famous anthropologist asked me to come and give a lecture at Cambridge and I said, “But I don’t even know what anthropology is!” So I went and read up on Lévi-Strauss and then gave a talk about our community and the dishes I had discovered through my research. After the talk, they all told me they were disappointed because they thought I was going to bring food for them to taste.

As somebody who had never been to university, never given a lecture, it was, for me, such a big effort to actually do the talk.

As somebody who had never been to university, never given a lecture, it was, for me, such a big effort to actually do the talk. But it was all the better for the academics listening because I was somebody who lived it. It was fieldwork that had been brought to their door, so they were thrilled, despite their disappointment at not being fed.

What about the people who shared their recipes with you? How was the response to your work there?

I discovered in myself this huge interest in my own community. I discovered what I had lost. Before it was something I had never wanted, never appreciated, or never thought of myself as part of but now it gave me great pleasure. Collecting the recipes was a huge pleasure for me too. Interviewing people was a way of keeping in contact with them. We all left Egypt but then ended up settling all over the world. I would write to people and family members I had been given contacts to and say things like: “I heard you know how to cook karabeej, could you give me the recipe?” and we would stay in touch. When my Book of Jewish Food came out [1996] I went on a book tour through various Jewish community centres in different cities in America. And there would always be somebody smiling a lot in the audience who turned out to be a cousin or someone who had given me a recipe. Once I met one of my aunts, who I hadn’t seen for 30 or 40 years!

What an amazing feeling it must be to feel like you have such a huge, global family – connected so strongly through food.

Another aspect was that sharing a recipe was a very, very personal and moving experience. Because for them, that recipe meant so much. When we were in Egypt, we would never exchange recipes outside of families, they were secret recipes belonging to the family but now we were all just trying to connect and were no longer rivals in family cooking as we had been.

When we were in Egypt, we would never exchange recipes outside of families, they were secret recipes belonging to the family but now we were all just trying to connect.

After the huge success of your first book a couple more followed and then in the early 1980s you did a book and a BBC TV series on Mediterranean Cooking. Is that when you really started travelling again?

I started travelling when my children left home, all of them, at the same time. One went to Manchester University and two went to New York one for a year and one for much longer. In Egypt, I had a very protected childhood. I never went on public transport. I never went on a tram or a bus. I never went anywhere without either a nanny (when we were little) or my parents. Later in Europe, I was always with my two brothers. Their role was to be protective guardians of the girls in particular. When I was a boarder in Paris, my brothers were in Paris as well. One as a medical student, the other as a boarder at the Lycée.

In London, I again lived with my brothers. I cooked for them and our friends (who still remember because the food in London was absolutely horrible at the time). After my children were born, I separated fairly early on from my husband, who then moved to America. So when I was able to travel I decided, I had to travel alone, which I did all over. And I decided that I wanted to go to the Mediterranean because the Mediterranean was where I felt most at home.

So when I set off, I set off à l’aventure, which means without deciding where to go but to start somewhere. I started with some contacts and they passed me on to others as I went along. Everywhere I went I felt I didn’t want to miss a minute. I introduced myself to every person that I met with: “I’m sorry, I’m a British journalist writing about your cuisine. Can you tell me something about your food? Can you tell me your favourite dish? And if you cook, have you got a recipe?” And it started me in conversations with people. For me, the recipes are always a person as well. The sharing of their recipes created a relationship because we would talk from there on about their lives and other things.

I met people who also wrote about food on my travels as well. Forty years ago in Turkey, for instance, I got to know someone who travelled from village to village researching all the regional foods of Turkey. She was the first person to write them down. She became a great friend. her name is Nevin Halici and she is now greatly respected in Turkey for her work and has done an enormous amount to raise the profile of the role of women in Turkish cuisine.

I did meet a lot of people on my travels, mainly women because I was researching home cooking, not restaurant food. But I did go to restaurants as well. Sometimes it happened, as in Spain, where I was invited by editors of food magazines and suchlike who said “I’m taking you to the top, top restaurant!” and the chefs would all be trying to cook like Ferran Adrià, who was getting really famous at the time. So I would go and we would eat fantastic food and then I would ask the chefs, “What is your inspiration?”. They would all answer: “my mother” as well as their history, region, local ingredients and so on. But then I would ask, “How would your mother have cooked this?”, which was a little bit offensive, wanting to know how their mothers would cook their dish because they were doing a new, modern version using all kinds of technology and tools and all that. But that is what I was interested in. The history and the lives of the people who created these dishes.

What’s really clear is that you have pretty much dedicated your working life to understanding education through food from a very domestic perspective. But also to one of the deepest, most essential ways of passing on knowledge: through talking about food, preparing food, and the transfer of social traditions and recipes as things that tie together cultural identity.

Exactly. And, also, I think, from the point of view of culture, because until more recently, food was not considered a subject of academic study. When I was starting out, the only time they mentioned food in an academic context was when they started offering “Women’s Studies” as a subject. Then, cooking was viewed as the chains that bound the woman to the house and the kitchen. Cooking didn’t set her free, it was a chore. There was nothing mentioned about the beauty in the preparation of food.

Now food has become a popular academic subject. Everybody eats. Not everybody plays music, not everybody writes plays or goes to performances, but everybody eats, so food is seen as a very important part of our culture. And although we all have our own very personal tastes and opinions about what we like, a lot of that has come through society because that is what we learnt at the beginning. And so food is a social condition too.

Claudia Roden CBE is a British cookbook writer and cultural anthropologist born in Cairo, Egypt in 1936. She is best known as the author of Middle Eastern and Mediterranean cookbooks including A Book of Middle Eastern Food, The New Book of Middle Eastern Food and Arabesque: Sumptuous Food from Morocco, Turkey and Lebanon as well as The Book of Jewish Food: An Odyssey from Samarkand and Vilna to the Present Day, The Food of Spain and The Food of Italy, Region by Region. She has also worked as a cooking show presenter for the BBC. Roden is credited with playing a large role in introducing the food of the Middle East and Mediterranean to Britain and the United States and her books have been published in many languages worldwide. The food journalist Paul Levy classes her with such other food writers as Elizabeth David, Julia Child, Jane Grigson, and Sri Owen who, from the 1950s on, “deepened the conversation around food to address questions of culture, context, history and identity.” Claudia Roden is also President of the Oxford Food Symposium and Honorary Fellow of University College London and the School of Oriental and African Studies.