Sometimes tragic and always fascinating, Ireland’s food history, with its strong connection to folk tradition, has been rather overlooked in Irish cultural studies says Caitríona Nic Philibín, who is helping to correct the gastro-critical record with her research on food customs in the Irish folkloric tradition. David Mellerick Lynch went to talk to her about Pishogues, Brídeogs, Butter Witches and more.

Seeds woven into the rushes of a St Brigid’s cross before planting; oatcakes prayed over then thrown against the household door to ward off hunger; a cross daubed in milk-froth on the back of a cow for protection against otherworldly mischief: Ireland’s food history is complex, rich, and rooted in subsoils both Christian and Gaelic-pagan in composition that has been somewhat overlooked in Irish cultural studies. Now Dublin-based academic Caitríona Nic Philibín is helping to correct the gastro-critical record with her research on food customs in the Irish folkloric tradition.

Having spent several years on the culinary scene, including spells as a chef in a retreat centre in Wicklow and a cookery teacher in the juvenile detention system, Caitríona transitioned into academia in 2019. Under the guidance of Dr Máirtín Mac Con Iomaire – the holder of Ireland’s first PhD in food history – she completed the Master’s in Gastronomy and Food Studies at TU Dublin before embarking on her PhD in 2022. Following Mac Con Iomaire, she has urged the wider recognition of Irish food as an intangible cultural heritage as defined by UNESCO, as well as advocating for greater engagement with Irish-language sources in relation to food customs and folklore.

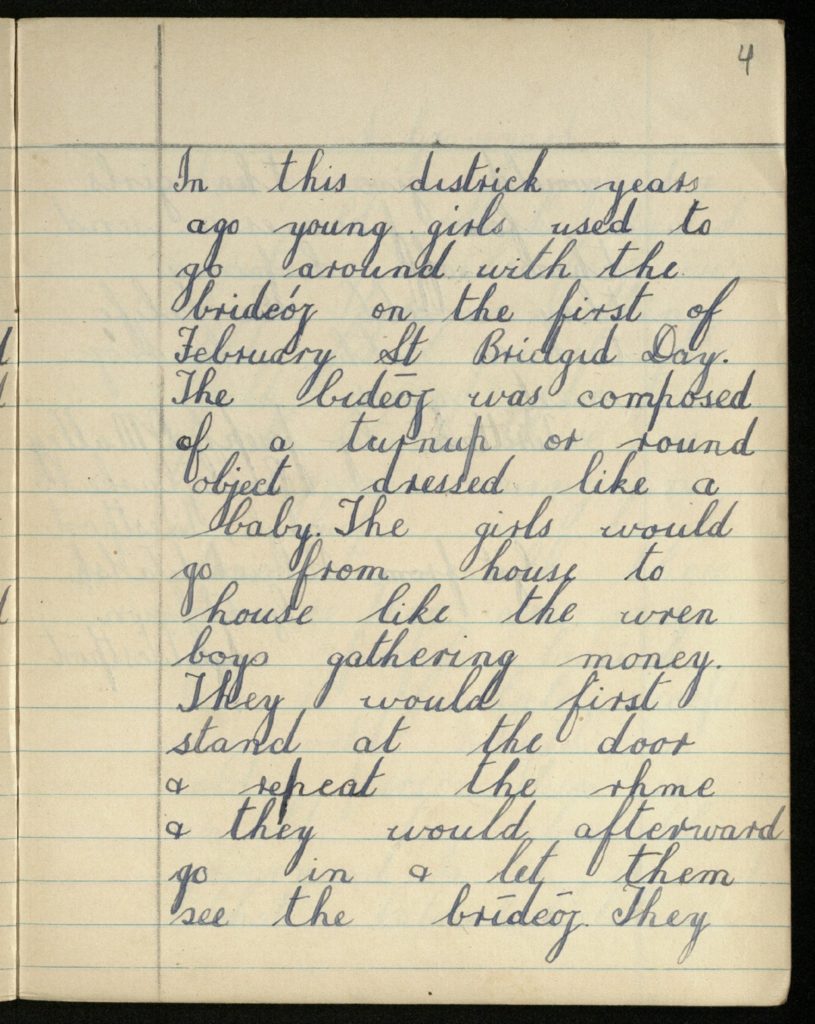

50,000 Irish schoolchildren deputised to sally forth, pens and copybooks in hand, and record the folk tales, oral histories, and recollections of customs past.

Indeed, much of her research draws from the digitised archives of the so-called Schools’ Collection Folklore Project, a sweeping and strikingly forward-thinking effort at oral heritage conservation run by the Irish Folklore Commission between 1937-38. This state-run project saw 50,000 Irish schoolchildren deputised to sally forth, pens and copybooks in hand, and record the folk tales, oral histories, and recollections of customs past – many of them fading into half-remembrance even then, in a young nation struggling to integrate the modern with the traditional in the post-colonial context – passed down by relatives and neighbours throughout their local villages, townlands and parishes. The resulting 6,000 copybooks of handwritten essays form an invaluable folklore resource and provided the documentary basis for Caitríona’s MA thesis on food customs relating to the four “quarter days” of the traditional Irish agricultural calendar.

For the small tenant farmers and rural labourers who comprised the bulk of the Irish population for most of the country’s modern history, the quarter days divided the year in both seasonal and spiritual terms. They provided a predictable rhythm to the year, a framework by which to organise labour as well as to give some meaning to the unreliable fortunes of lives lived very often on a subsistence basis, in grinding poverty. Imbolg, the first of February – also celebrated then as now as St Brigid’s Day – heralded the coming of spring, the start of the farming year and the milking season. Accordingly, the day and its customs brought with them a sense of lightness and optimism, with the darkness of winter in abeyance and the promise of a replenished larder becoming tangible.

For the small tenant farmers and rural labourers who comprised the bulk of the Irish population for most of the country’s modern history, the quarter days divided the year in both seasonal and spiritual terms.

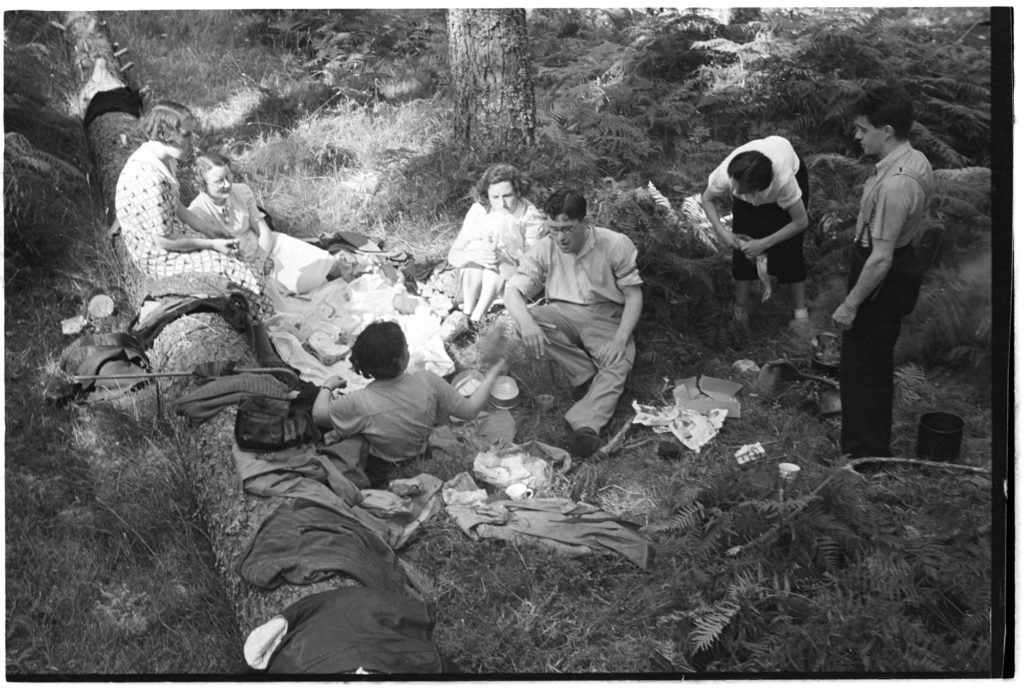

By contrast, May Day or Bealtaine, though marking the first day of summer, was characterised by a more fearful atmosphere, as the dependability of the coming harvest came into question, and stories abounded of bad luck or even outright malevolence (particularly around the theme of dairy loss and thievery). The festival of Lughnasa on the first of August revived the celebratory spirit as the harvest began and bilberries, a variety of wild blueberries, came into season; the first potatoes brought connotations of good luck, while hilltops became sites of feasts and fairs. Finally, Samhain on the first of November continued the spirit of festivity with games such as snap apple and bobbing for apples – still widely played on today’s Halloween – while simultaneously ushering in the winter and its attendant hardships.

Food was central to the quarter days. As Caitríona explains, “the agricultural significance of these days inextricably linked them to food production, storage and consumption”; this was manifested too in the meals traditionally eaten, as well as, more abstractly, in the crop harvests and dairy yields to be prayed for and symbolically protected. At Imbolg, potatoes were enjoyed in the form of boxty, a kind of fried pancake made of the tuber grated and mashed, and poundies, potato mashed with butter, salt and onion. Bilberry jam featured at Lughnasa, while Samhain boasted two unique delicacies in gran brec, a boiled and sweetened wheat grain beverage drunk after divination games, and báirín breac, a type of fruit loaf. Báirín breac (barmbrack) is still eaten in Ireland around Halloween and, then as now, comes with its own game literally “baked in” in the form of a ring hidden in the dough, ordaining – or condemning – the finder to marry within the coming year. However, absent from today’s commercially produced bracks are the host of other objects and trinkets included to prophesy fortunes both good and ill: a coin for wealth; a piece of cloth for poverty; a matchstick for an unhappy marriage; a button for a life of singledom; a medallion of the Virgin Mary for the imminent onset of a religious vocation.

This latter tradition in particular highlights the importance of superstition and mysticism – often compounded with a peculiarly Gaelicised flavour of Catholicism – in the Irish food customs mix. It is arguably around Bealtaine, May Day, that we see this most clearly. As mentioned, this quarter day brought with it an undercurrent of foreboding somewhat at odds with its summer setting. Like Samhain, Bealtaine represented a liminal space where the boundary with the otherworld of the sidhe grew thin; mischief abounded, and farmers did what they could do to surround their livelihoods with charms of protection. There were the aforementioned crosses drawn with milk froth on the backs of cows, as well as sprinklings with holy water and charms with rowan berries; fire was also commonly used, with cattle in some cases being driven between bonfires or over hot cinders as a form of spiritual prophylactic (indeed, one reputed etymology of Bealtaine stems from the pagan god Baal, in whose honour the ancient druids would allegedly light the great fire at Tara on May Eve).

This highlights the primacy of cattle and dairy in Irish culinary life, stemming from the mythological cattle raids described in the Táin Bó Cúailnge and other ancient epics. Butter formed a major fat source in the Irish diet, and many of the quarter-day customs were oriented towards the safe chaperoning of the milk not just through its generation by the cow but all the way through the churning process. The folkloric record demonstrates that at Bealtaine, butter threats were seen as emanating not only from supernatural influences but also from the all-too-human depredations and jealousies of neighbours; there is abundant oral evidence of pishogues or hexes being set by farmers or their wives against their local rivals, whether by taking the form of a hare to go out and “steal the butter” on May Day morning, or by skimming the water from a neighbour’s well, or by the chanting of such incantations as, “The tops of the grass, the roots of the corn, my neighbour’s milk both night and morn.”

“The tops of the grass, the roots of the corn, my neighbour’s milk both night and morn.”

Interestingly, the prevalence of such stories of malign “divilment” and intercommunal suspicion somewhat give the lie to the notion some may tend to hold of an idyllic, socially cohesive past. (These forces of bad luck nevertheless often had their own rules and structure to adhere to: Caitríona relates the example of how lending one’s churn to a neighbour at Bealtaine “could result in the owner getting a poor return on their churning efforts for at least four churns upon its return”.)

Furthermore, the general anxiety around cattle in the Irish psyche can be seen to persist today, manifested in the ongoing debate around the “national herd” and its uncomfortably dual role as both a major export driver and a significant greenhouse emitter for Ireland; in this context, Caitríona points to sociologist Corey Lee Wrenn’s suggestion that “vegans are the butter witches of the modern day, an untrusted feminine force” setting metaphorical or political pishogues to hex the dairy yield at the GDP level.

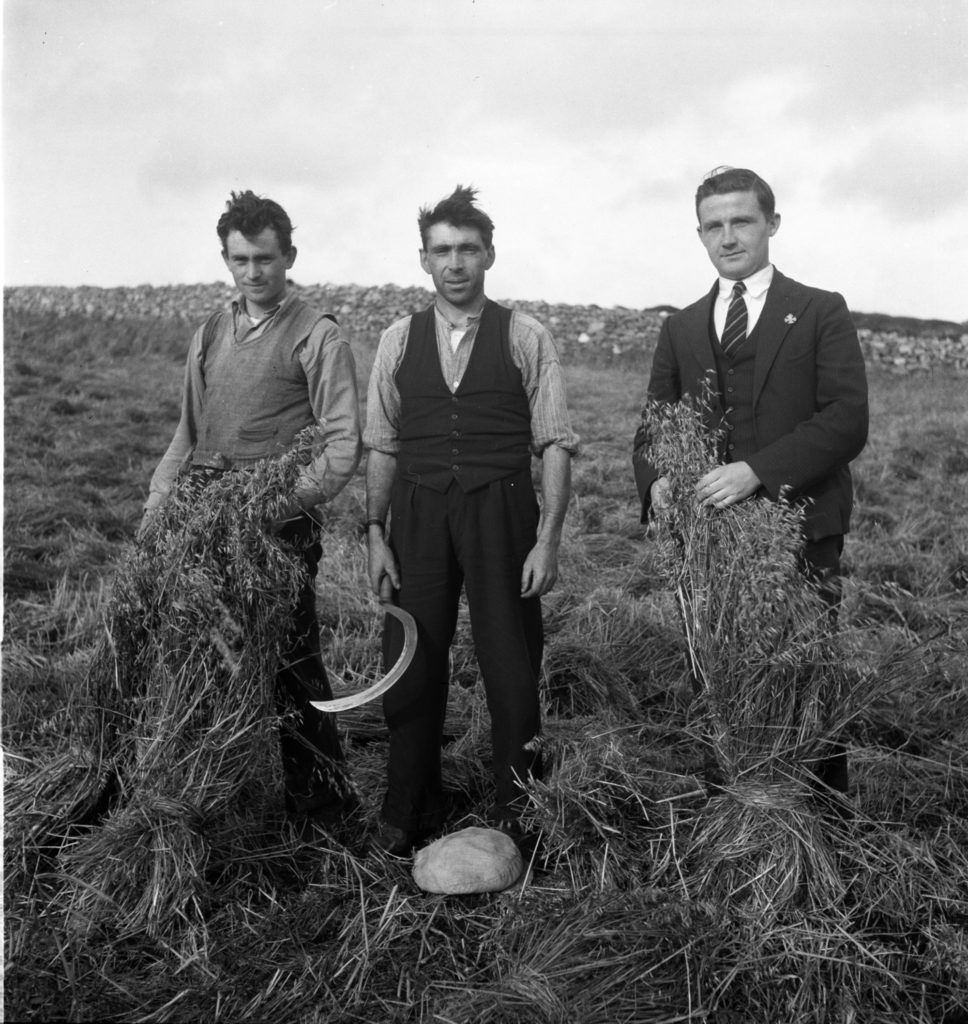

However, the “butter spirit” had its way of bringing communities together too: one notably pagan-inflected Imbolg custom saw groups of “biddy boys” or young men from a given locality going door to door with a Brídeog, a doll fashioned from the “dash” or staff of a butter churn and with a turnip for a head; sustained on whiskey and porter, they would perform and play music for the householders they visited in a good-humoured project of general entertainment – and in the expectation of a reward of eggs and money for their efforts.

In all, though gastro-criticism in Ireland still appears to be in its nascent phase, there is gathering interest in this side of Irish culture with academics like Caitríona and Máirtín Mac Con Iomaire performing imaginative and innovative research. For Caitríona – currently in the midst of her PhD, with the support of the Irish Research Council – the study of food heritage offers professional opportunities as well as a new lens for examining Irish history and the Irish people; but it has personal resonance too. In her own words, “Food has always been central to the celebration of all of the significant moments in our lives and many of the dishes that evoke an emotional or nostalgic response in me are present in my day-to-day research.”

Caitríona Nic Philibín is a chef, PhD student at the Technological University Dublin and Irish Research Council scholar. She is passionate about all things food-related, particularly Irish food and its customs and traditions. Caitríona’s research focuses on food in Irish folklore. Her current research project, supported by the Irish Research Council, aims to shed light on food traditions found in the National Folklore Collections 1937-8 Schools’ Collection and the 1956-7 Schools’ Collection in the Ulster Folk Museum, creating an all-island account of Ireland’s food traditions.

David Mellerick Lynch is from Cork, Ireland and lives in Berlin. He is a graduate of Trinity College Dublin and has an MA in Creative Writing from the University of East Anglia. He has been published in a variety of online and print journals, including The Bohemyth and The Stinging Fly.

Title image: “Harvesting with horse-drawn reaper and binder” c. 1935, Lú. Photo: Maurice Curtin, by Dúchas © National Folklore Collection UCD.