Nathan Thornburgh is a former senior Time Magazine journalist who now uses food as a lens for telling people’s stories. Together with Matt Goulding, he is the co-founder and publisher of Roads & Kingdoms. For several years, he worked closely with Anthony Bourdain on the Explore Parts Unknown series and the travel podcast The Trip. Here, he talks to The Common Table about print as self-care and how food can form the soul.

Sophie Lovell: Let’s start by asking you to introduce yourself. Could you tell us who you are and what you do?

Nathan Thornburgh: I am, above all, an editor; that is my life’s calling. I was a journalist and a foreign correspondent at Time Magazine for about a decade, but through a series of events that included being arrested in Cuba and experiencing the futility of our style of geopolitical reporting, passion fatigue set in.

I then got very interested in food as a vehicle for telling these stories because, one, it’s less likely to get you arrested while on assignment. And two, I met the food writer Matt Goulding. Matt and I both found that if you go to difficult places and start talking about something as common and good as cooking, eating, and food traditions, then you can break through some of the alienation between readers and subjects. Food is a tremendous lens to see the world through; it makes very disparate people seem more vivid and more human on the page. That was the goal.

Food is a tremendous lens to see the world through, it makes very disparate people seem more vivid and more human on the page.

We started talking about this in 2009, then launched Roads & Kingdoms in 2012. We spent half of the time between then and now with Anthony Bourdain as our main partner and collaborator. He joined us pretty shortly after we launched back then, and was with us on the journey until his death in 2018. We have done a lot of things together in his very, very large world and are continuing that work. We’re in league with his family, through his trust, through a lot of his friends and networks and through the trips that we do. José Andrés [chef and founder of World Central Kitchen], in particular, is a mutual friend who is now also an investor and editor-at-large at Roads & Kingdoms.

So we’ve had lots of ups and downs as we’ve gone along, but now here we are at the end of 2025, making our first print magazine in this oddly thrilling moment in media. Despite all the challenges that the media has had, we’re feeling happy that we’re finding our audience and in particular, with print, we’re finding a kind of one of the correct ways of reaching them. So that’s the moment you’re finding me in. I’m feeling strangely and improbably optimistic. Print is self-care; it is restorative.

Orlando Lovell: In the 13 years that you’ve been working in this field, do you think your goals and perspectives have changed?

Nathan Thornburgh: 2012 was a weird time to start a media project, particularly an online-focused one, because there was so much venture capital interest. This was when Vice joined the Dark Side in terms of its business model and growth. This had a big influence, particularly in New York, on how people thought about media. That you should be taking in investment and growing rapidly. There were also a lot of other models that were focusing on an almost a proto-algorithmic click farming through their content.

I think our goals haven’t really changed; we were always stubbornly focused on old-fashioned, long-form storytelling, but the climate has changed among readers.

I think our goals haven’t really changed; we were always stubbornly focused on old-fashioned, long-form storytelling, but the climate has changed among readers. They are now conditioned to pay for content they value online as well as offline, with something like a print magazine. Whereas back then, people just expected free, beautiful content as a sort of birthright, not as a privilege or something that you have to support. So I think we’ve stayed the same, but the market, the mood and the relationship with readers have evolved.

Bourdain was an amazing partner who instilled a lot of poor business habits in us.

And that’s good news for us. I have a lot of ownership on this, in a bad way, because Bourdain was an amazing partner who instilled a lot of poor business habits in us. He would do like a lunchtime panel for Capital One or something, they would pay him a lot of money, he would break us off a big chunk and say, “Go publish something weird and beautiful”. And we would do it. We got to publish a lot of great stories that way. But there was no business model behind it, except for this great pirate patron that we had. So when he died, we realised, “Oh, wait, we haven’t actually built a mature media business here”. Now I think we’re finally in this mode of finding out how to build a sustainable media business without Bourdain chucking money over the fence. So, yes, I’ve changed as a business person. I think I’ve gotten more sober and sophisticated.

Orlando Lovell: As a journalist, do you still believe in storytelling? How do you tell stories now? Across a diversity of media or around the fireside and the kitchen table on your Roads & Kingdom’s Trips?

Nathan Thornburgh: Absolutely, where we’re at now is only because we started the trips project, which we call the League of Travelers. I had a lot of misgivings at first because essentially these are very high-end culinary tours. They are about a week long, super deep dive, and with a high price point of at or above $10,000 per traveller per week. We actually talked about this idea when Bourdain was alive, and he, somewhat predictably, thought, “What a fucking nightmare travelling with strangers on a set itinerary”. He had visions of chasing the red umbrella across the piazza or something. Even then, I was trying to talk him down by explaining that it could feel like the production work that we did, which was also always with a 10-person crew on a week-long mission with great characters and cinematic moments and a narrative that you’re tracking down.

What we’ve tried to do with the League of Travelers is make it as much like journalism as we can in a hospitality setting.

What we’ve tried to do with the League of Travelers is make it as much like journalism as we can in a hospitality setting. It’s storytelling with real characters and great experiences with places that we’ve reported from before and journalists that we’ve previously worked with. It’s always impossible to know what Tony would think about something, and I can’t speak for his evolution on that, but I can say that we’ve been really happy with the way we were able to marry journalism and travel experience.

For me, despite my misgivings, I’ve really enjoyed not just putting these trips together, but actually being on them, and being one of the hosts in rotation. It’s not something you can know in advance… When I started out as a journalist, it wasn’t necessarily because I loved people. As a writer, you want to work on your craft and be left alone. But I’ve really come to enjoy this project.

Raining content down on people’s heads is not enough these days to satisfy all of the kinds of things that people are increasingly not able to include in their daily lives.

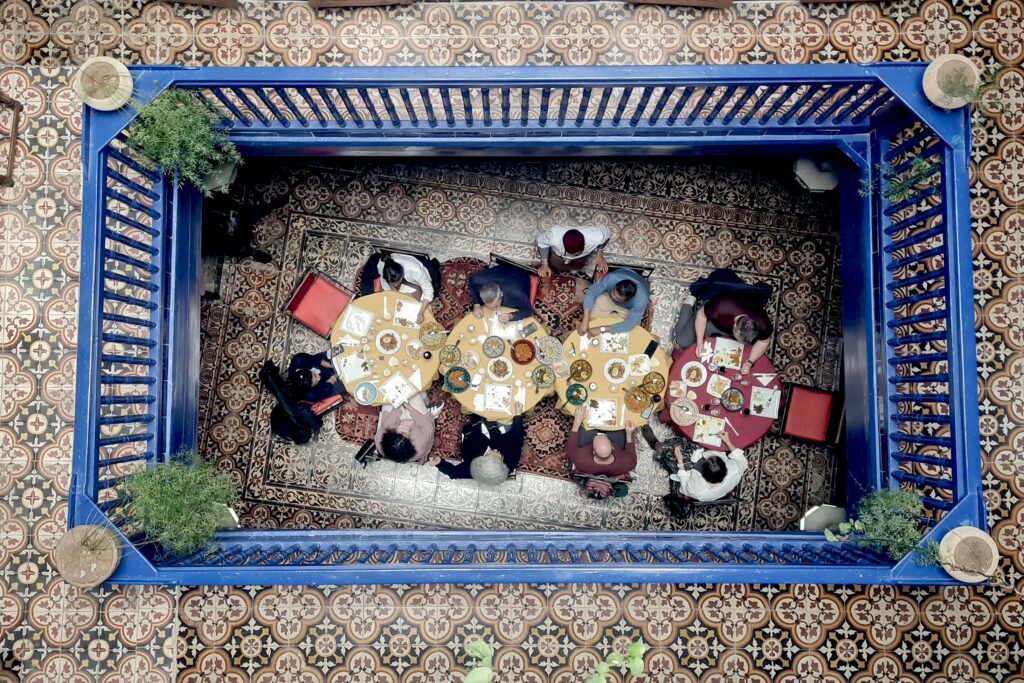

Real-world experiences are something people are hungry for. Just raining content down on people’s heads is not enough these days to satisfy all of the kinds of things that people are increasingly not able to include in their daily lives – long tables, common tables, and so on. I think mutual experiences are valued yet underprovided in the lives that a lot of our readers lead. That said, we keep it contained. We don’t want to be doing 100 trips per year as a giant business. We want the League of Travelers to work neatly with journalism and our ability to print or create other types of content as a small team.

Sophie Lovell: Food is perhaps the most culturally charged, unifying and universal dimension of travel and hospitality. It is a powerful and universal social connector, as is storytelling. Who are your storytellers? What are the most important stories to tell? And what do you want your listeners to take home?

Nathan Thornburgh: Are you talking specifically about the trips or the magazine?

Sophie Lovell: Either or both, you choose.

Nathan Thornburgh: That’s a good question. I would say my favourite class of storyteller at this point is the producers; the people who are growing things, fermenting things, distilling things. I think they have really important voices as stewards. Not to be sanctimonious or anything, but it’s just true that they are protecting the Earth. They’re the start of our supply chains. They are guarding traditions. In a lot of cases, they are fighting every day against an uncaring economic system. So they have these very urgent stories that also happened to be delicious and forming to the soul.

The producers, the people who are growing things, fermenting things, distilling things, have really important voices as stewards. They are the start of our supply chains. They are guarding traditions.

Those are people who we’re constantly trying to bring into the storytelling on our trips whilst mediating them with great writers or filmmakers. They’re who we want to make content around. The more we can have them tell their own stories, the better.

I just had the opportunity, which is one of the ridiculous privileges of this job and this life, to go and visit pulque makers with Juan Escalona up in the villages outside of Mexico City. Pulque is a traditional pre-Columbian fermented beverage. I spent a day in these insane Agave fields of three-metre-tall dinosaur plants with the tlaciqueros, whose job it is to tend them and keep them safe from poachers. The processing of pulque is a very finely tuned schedule of sterilising the plants, bringing the heart out, scraping it, letting the nectar emanate, and then fermenting it. It’s such a ballet. Escalona does this with such grace and humility. Pulque is a drink that cannot travel; it dies after a few days. So you really have to be right there to drink it. It’s hard, even for it to get, in a timely fashion, into Mexico City.

That trip reminded me again of what a privilege it is to get to know those people who are still creating these products that are both timeless and yet very much a part of the modern fight for the soul of Mexico and Mexican cuisine.

We published excerpts of Juan Escalona’s new book ¡Qué Viva el Pulque!, in our magazine, and we’ll be with him on a couple of trips I’m leading with my Mexico City partner in January to bring our travellers into the world of pulque.

Orlando Lovell: One of the effects of industrialised living that we come across so often is that the respect for food production has been lost because the connection has been lost. Would you say that part of your task is to educate people, to restore a sense of thankfulness and reverence, or respect to the act of eating?

Nathan Thornburgh: Just to be clear, I have nothing to teach anyone. I’m just as blind in the cave as the rest of us, but I think bringing people into those contexts where they can see this connection happening is important. We had a great run of trips, which we will hopefully repeat, where we were killing at least one ruminant on each of the trips to eat. This is killing that is not out of vengeance or spite. That’s why it felt like success to me, to be in these moments where we would sacrifice a lamb or a goat for a barbacoa. That kind of experience is always life-changing.

I have nothing to teach anyone. I’m just as blind in the cave as the rest of us, but I think bringing people into those contexts where they can see this connection happening is important.

I will go home and just crush a smash burger two months later as if I had forgotten where meat comes from, so I’m guilty of this sort of amnesia, too. But at least for some period of time, I think people are really transformed and brought out of their modern relationship with meat into something that is, by necessity, more thoughtful and impactful. So, yes, that is a teaching moment, for sure.

Sophie Lovell: With your League of Travelers, as you mentioned, you create these bespoke trips to extraordinary places with a small number of paying guests or customers. What are your feelings about luxury and food travel? Is it okay for them to coexist? How do you balance the proximity of wealth and access with inequality and poverty, or worse, that food travel necessarily brings with it?

Nathan Thornburgh: Well, the minefields are immense, right? This idea that I’m bringing ten millionaires to watch an Oaxacan woman throw clay, or something, is constantly on my brain. One of the ways that we engage with that issue is that we compensate everyone involved extremely fairly. There are times when that makes a meaningful difference. There are times when it doesn’t. We only go one time a year, so I’m not claiming I’m saving anybody’s bottom line, but I think we try to be useful and support people who can really use the support and are worthy of it. So, on that level, I hope we’re a kind of money laundering operation that is for good.

We are not presuming to explain these places. We always have a local host, and it’s nothing more than the best version of their world that we’re showing.

The other issue is the hubris of saying, for example, that you’re going to explain Oaxaca in a week. Bourdain also had to deal with this concept as he travelled, you know, to all of these places where he had only a very minimal understanding, or sometimes no background in the place, and then try to create something that felt authentic and not totally out of his lane. We are not presuming to explain these places. We always have a local host, and it’s nothing more than the best version of their world that we’re showing.

Sophie Lovell: What are your long-term goals with Roads & Kingdoms? What would you like to do next that you haven’t done yet? Where would you like to travel, where you have not yet been?

That’s a very dangerous question to end with, especially the “Where would you like to go?” That is where I think we could really lose the plot, because I want to go everywhere. Seriously, I want to go back to the places I’ve been 100 times, and I also desperately want to go to places that I’ve only ever read about in magazines. I’m not going to be able to do that, so I have to shrink into myself a little bit and say, “All right, we’re going to focus on a few new destinations a year and try to expand from there”.

But for Roads & Kingdoms and me personally, I would just love to be able to have the journalism side support itself. We have printed a certain number of magazines, and my job right now is to sell these magazines, because that’s how we get to make another one and maybe do more than one a year. We have just put in a year’s worth of love, attention, and our best writing, photography, illustrating and editing, but I want to do more of it. That’s really my only goal, to be able to continue the trips in a way that feels as fun and rewarding and contained as they can be, so that we can do more journalism and have that be the centrepiece of the company. As I think you guys can appreciate, that is both a very humble goal and also outrageously ambitious. I’ve got a lot of nerve expecting a magazine to pay for itself.

Nathan Thornburgh is a former Time Magazine senior editor and foreign correspondent who has reported everywhere from Russia to Myanmar to Iraq. He is also the co-founder and co-publisher, together with Matt Goulding and Doug Hughmanick, of the media and travel company Roads & Kingdoms. Business partners with José Andrés and the late Anthony Bourdain, and winners of four Beard Awards, a National Magazine Award and a Primetime Emmy, Roads & Kingdoms published their eponymous first print magazine in December 2025.