A consortium of collectives including architects, urbanists and ecologists have developed a master plan for a whole country, centred around food production. The aim is to make Luxemburg carbon-negative by 2050 by changing diets and land-use practices.

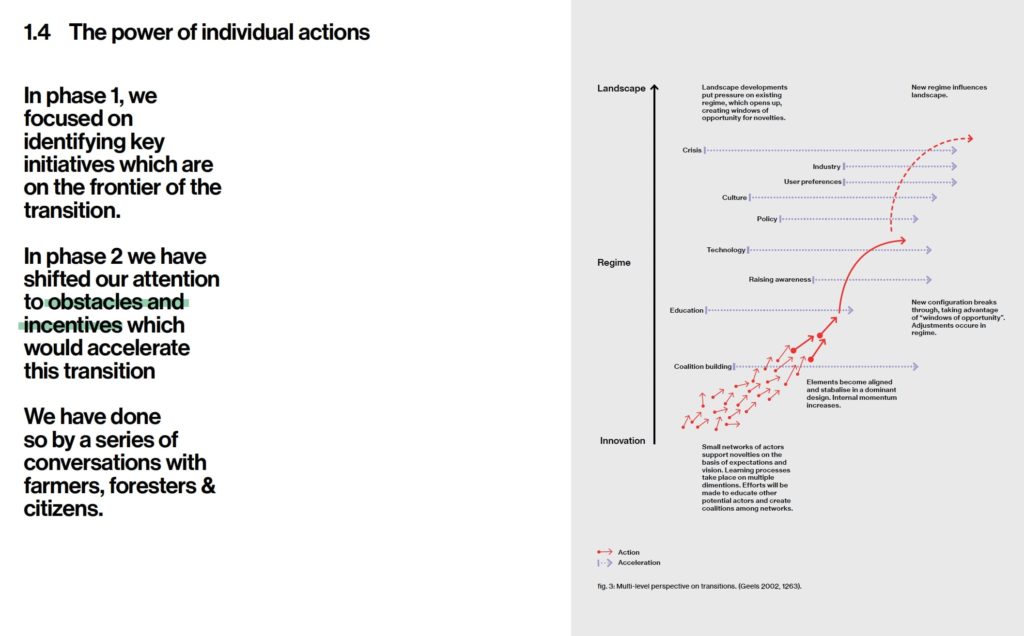

Belgium-based 51N4E is one of a growing breed of collectives who understand that the problems the world faces cannot be solved by lone geniuses or individual companies and organisations but require combined effort on a considerable scale. From predominantly architecture and urban planning backgrounds, what they do is act interstitially, organising supportive processes needed for collaborative design. In other words, recognising the enormous complexity of the problems – and therefore transformative solutions – involved in adapting to and combating climate change, they work together with other practices, groups, authorities and communities in order to come up with in-depth, holistic responses.

One of these responses is a socio-economic master plan for an entire country: Luxemburg. And because – even for urban planners – no future-proofing scheme for the climate emergency anywhere can be complete without considering food, this project involves a radical transformation of the dietary habits, land use, energy and food trading practices for the whole of Luxemburg – all 42,193.47 square kilometres of it. Together with Luxemburg architects 2001 and landscape and environment practitioners LOLA from the Netherlands, 51N4E formed a consortium to respond to a call by the Luxemburg Ministry of Energy and Spatial Planning to create a master plan for how the country can effectively and sustainably achieve carbon neutrality by 2050 as per the Paris Agreement.

Their proposal addressed some of the big, difficult questions that every nation needs to ask itself right now: How do we define growth? How can we live a more balanced life? How do we consume not too much, yet not too little? Do we need to change our diets? and: Can our territory produce the food we consume? Whichever way a country chooses to answer these questions, it is clear that there are to be no solutions without accepting the need for drastic shifts in the dominant socio-economic models.

As the planning consortium looked into the task of achieving carbon neutrality for Luxemburg by 2050, one question became a clear point of focus, says architect Arya Arabshahi of 51N4E: “How do our food preferences and cravings impact the trajectory of climate change?” Thus what began as a territorial spatial planning assignment became a mission that also required tackling decarbonisation.

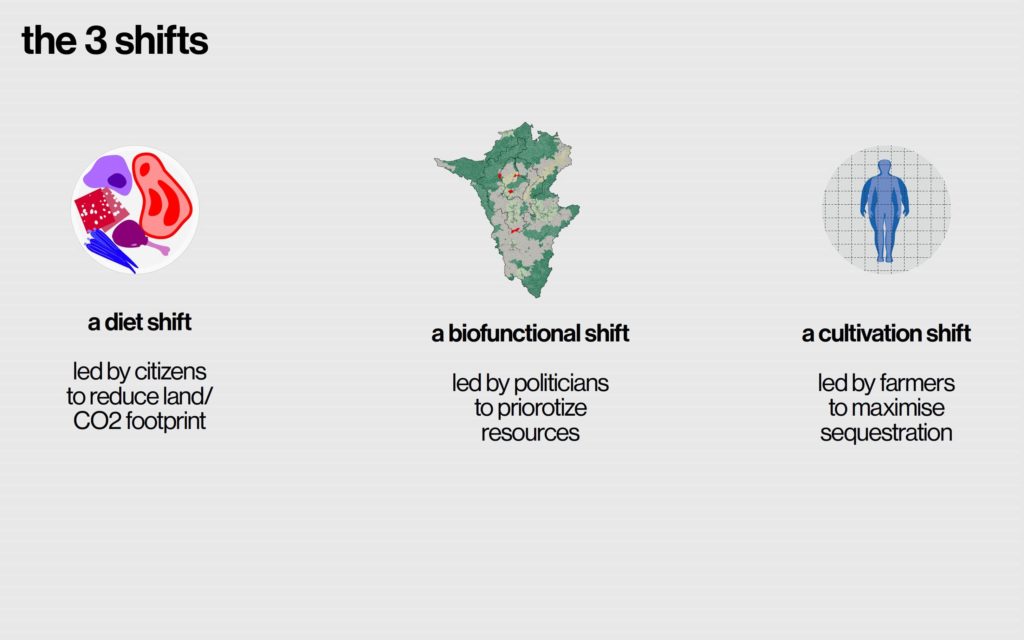

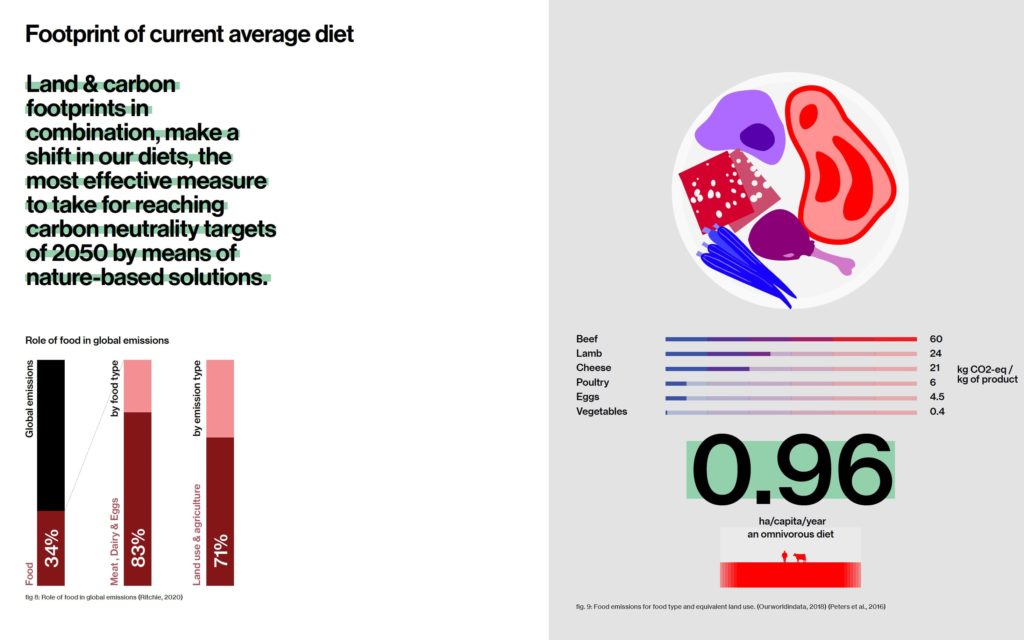

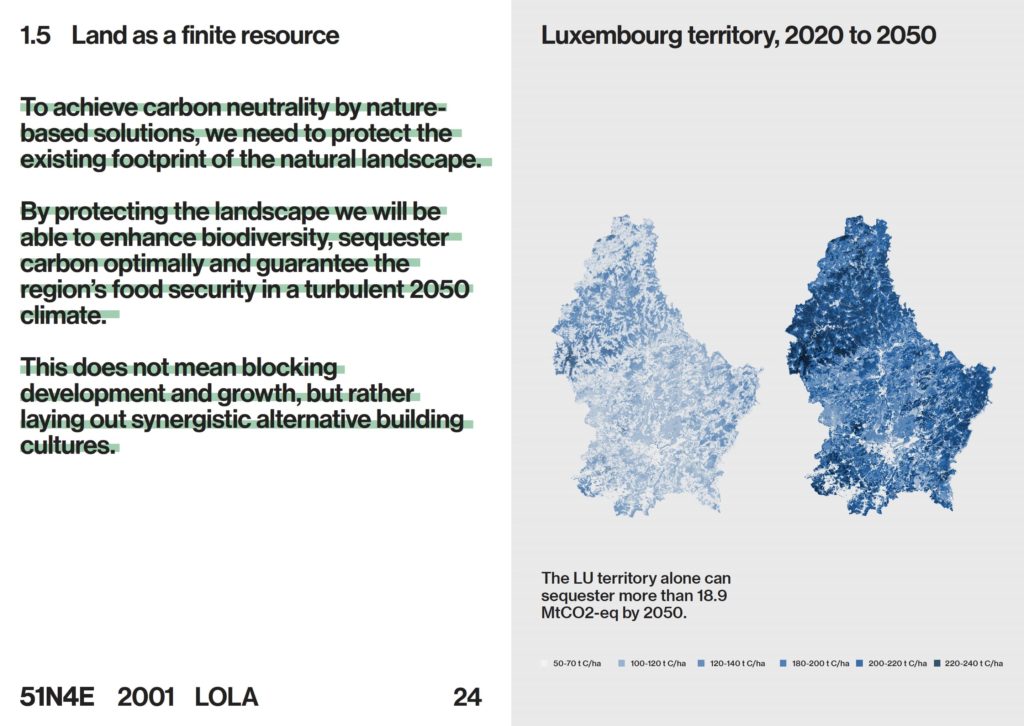

Food is responsible for almost 30 per cent of greenhouse gas emissions. This includes emissions from land use, agriculture, animal feed, transport, packaging and waste. But land use and agriculture together form 70 per cent of these food GHG emissions. “So”, says Arabshahi, “taking land and carbon footprints in combination plus a shift in the national diet patterns the most effective measure that can be taken to reach the 2050 carbon neutrality targets is by means of nature-based solutions.”

Arabshahi goes on to explain that from diet to forestry practices, the nature-based decarbonisation path is deeply interlinked. With his consortium’s collective master plan, called Soil & People, he says “We have laid out a step by step path for achieving a bold yet feasible goal in emissions touching on agriculture, land use, forestry and food systems as a whole. This step by step balancing act enables the region to feed itself, reduce its food emissions and enhance negative emissions beyond any of the current projections.”

So how does it work? The carbon footprint of the Western diet is large, say the consortium, and continue:

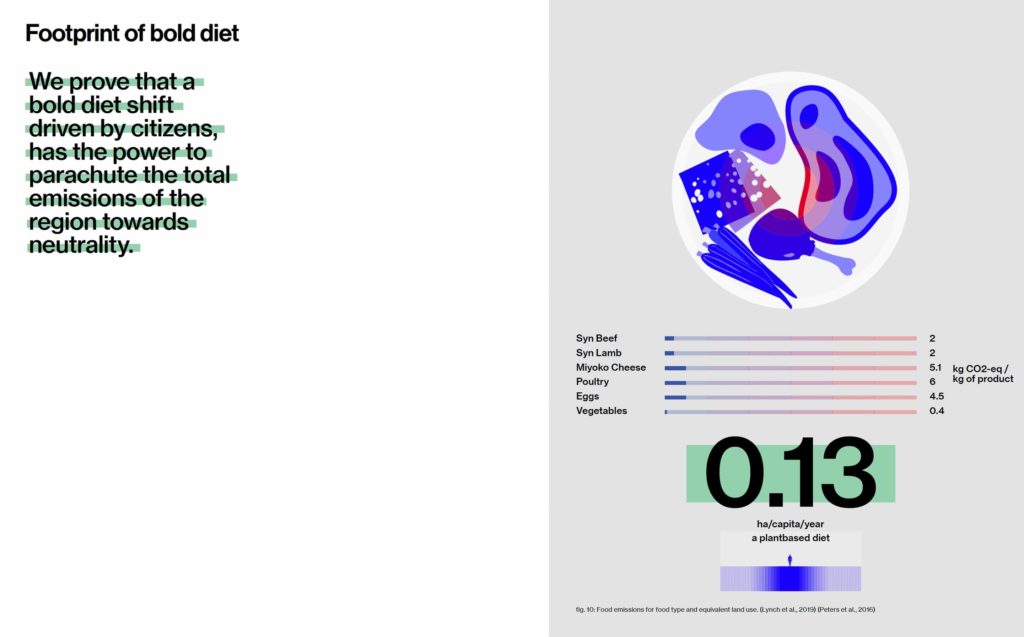

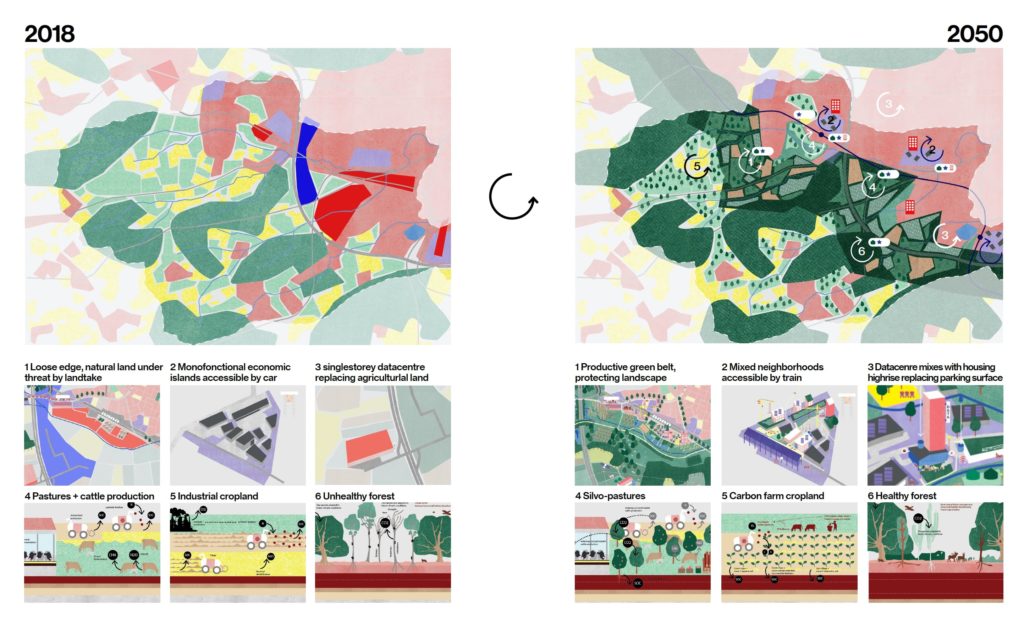

“An omnivorous diet requires almost seven times the amount of land (soil) that a plant-based diet takes up. Since land is a finite resource, especially in tiny Luxemburg’s 2,586 square kilometres housing a population of 632,000, the impact of such a demand for land is clear. Studying the growing demand for plant-based food, we assumed a bold shift in the country’s diet in the years leading up to 2050. The average Luxembourgish diet today contains one plant-based meal per week. We foresee this to increase to one plant-based day per week by 2025, half of the week by 2035, and six days a week by 2050.

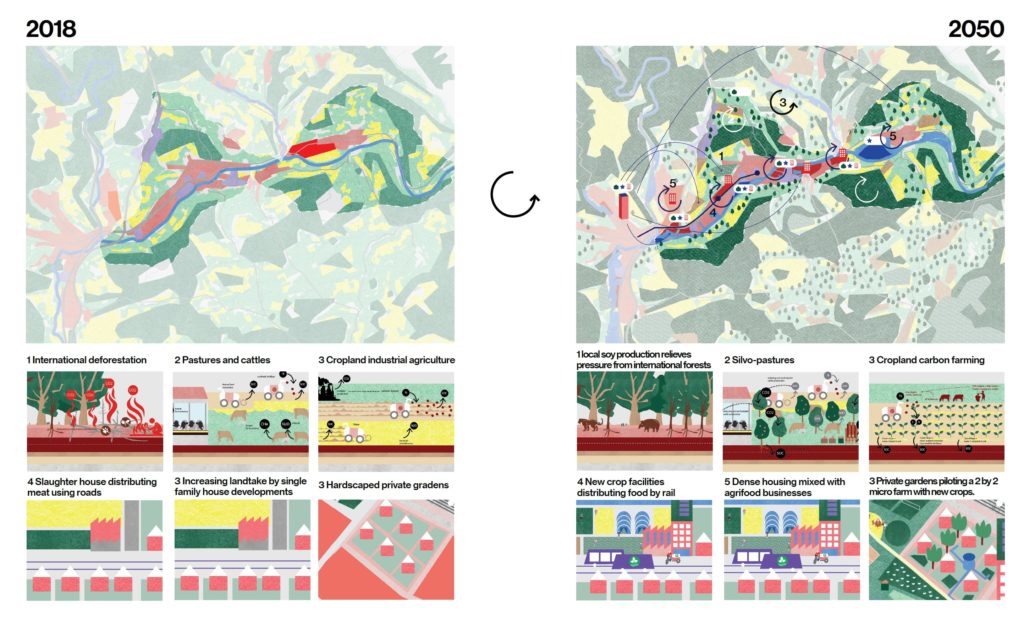

“It must be noted that we have also taken into account meals that are not plant-based but have a carbon footprint equivalent to a plant-based diet. The price and footprint of lab-grown meat, for example, is decreasing rapidly and could become a viable option over the coming decade. Taking these bold assumptions into account, we have calculated that Luxemburg will be able to reach food autarky by 2045. It will also relieve land from food production from more than ten per cent of the country.

“For farmers, however, this transition will be both economic and cultural. Many of the Luxembourgish farmers have been practising cattle farming for generations and they see it as part of their heritage. There are also political and economic factors at play including the demand for meat and dairy and the structure of subsidies. For this transition to occur, farmers need consultation on the added values of the transition in addition to a nationwide conversation about the definition of agriculture, common values and which of these values must be kept in the long term.

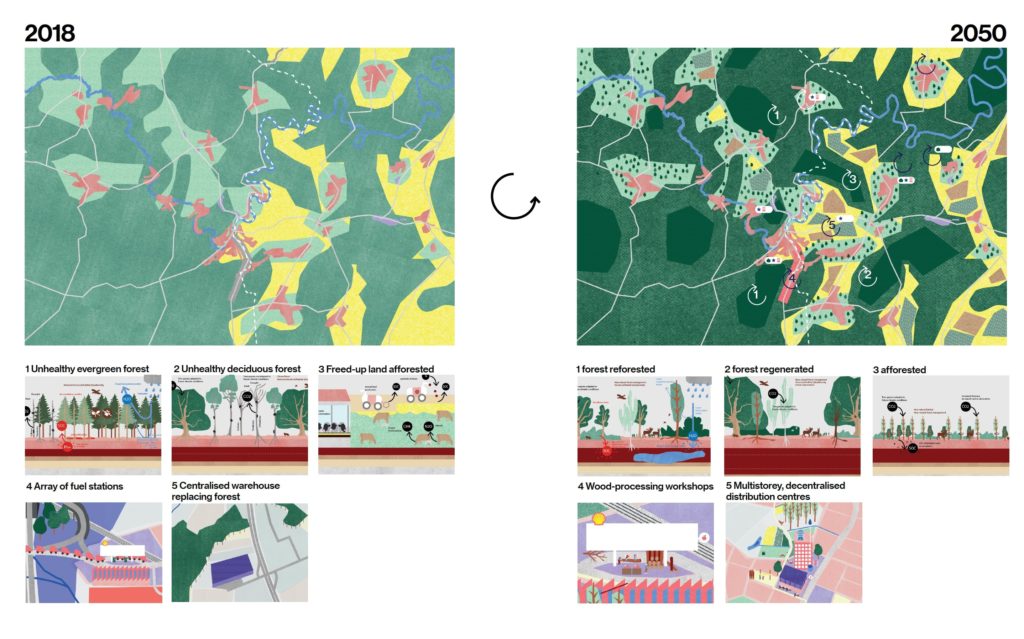

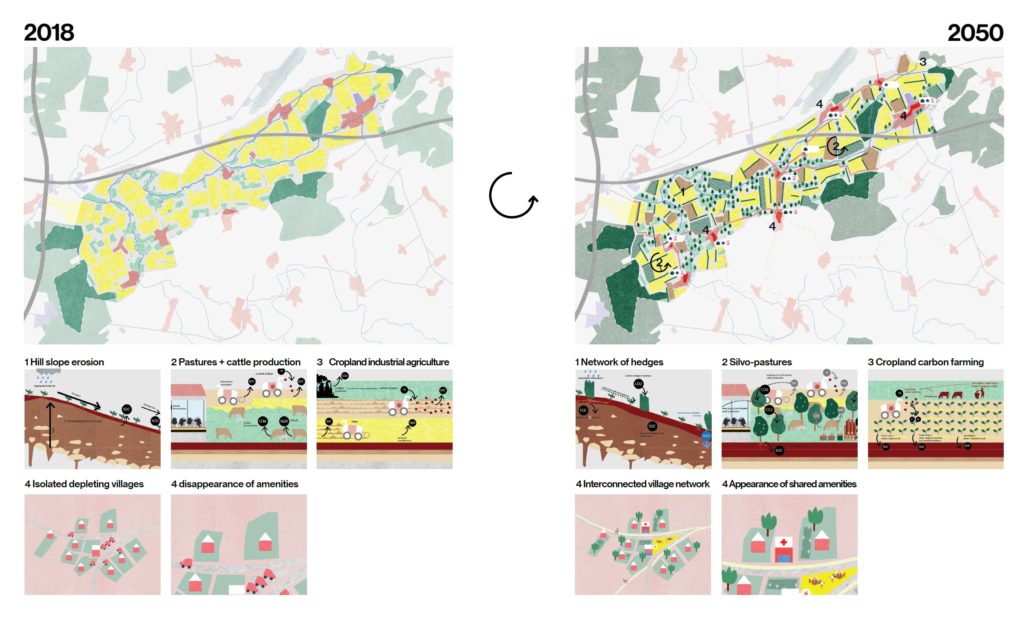

“What can be done with the ten per cent of land that is freed up from agricultural production? We developed a land management tool where population shifts, diet shifts and climatic conditions are taken into account when assigning land use to natural landscapes.

“Since we aimed at maximum sequestration of CO2, and after evaluating the climatic conditions and productive capacity of the territory, we designated areas of reforestation in proximity to existing forests. We also reimagined a rearrangement of the cattle and crop cultivation of territory to best match the climatic conditions of 2050.

“In addition, we investigated a cultivation shift whereby agricultural practices adopt decarbonising measures. Namely planting hedges and elevating pastures to silvopastures (where trees, forage and grazing are integrated in a mutually beneficial manner). These silvopastures will have economic advantages for cattle farmers as they can have byproducts such as fruits and nuts. In addition to reducing carbon footprint, silvopastures infiltrate water and contribute to biodiversity. The arable lands that are transformed into forests can also be seen as a resource for wood production and can feed the growing demand for timber in the construction sector, and as a result, reduce the cement-infused carbon footprint.”

There tends to be a sense of utopian generalisation when it comes to master plans. How can you persuade a whole nation, brought up eating pretty much whatever they want, to change their diets? How do you differentiate forests grown for wood and other ecologically dysfunctional monocultures? How do you solve the tangled political and ideological issues around dairy farming practice, tradition, subsidy and ecology? But implementation issues aside, the very fact that Luxemburg is asking landscape architects and planners and ecologists to develop such holistic decarbonisation visions on a huge scale with food and people, and soil at the centre, is heartening. And heartening is what is needed with the daunting radical change humanity faces, because, in the words of climate activist Rob Hopkins, “The journey from a high-carbon to a low-carbon world has to feel like something we long for … We have to make space for collective yearning”. We need future-proofed, well-researched narratives we can both believe in and work towards.

The Soil & People spatial vision for the zero-carbon and resilient future of the Luxembourg functional region is a project shortlisted by the Luxemburg Ministry of Energy and Spatial Planning from their 2020 Luxembourg in Transition open call. The core development team are 2001 (LU, architecture), 51N4E (BE, urban transformation), and LOLA (NL, landscape & environment), together with: Systematica, Transsloar, Endeavours, ETH Zürich, TU Kaiserslautern, Yellow Ball, Gregor Waltersdorfer, Maxime Delvaux and Offices for Cities.

All images courtesy 51N4E; Title image © Chloé Nachtergael, 51N4E