Designer architect Rianne Makkink talks to The Common Table about how her studio turned urban planning on its head by rethinking the existing urban structure of Rotterdam’s harbour area. Their plans not only include an energy transition, but also a new vision for communal “work-living” centred around food – complete with low-impact resources such as mushrooms, insects, duckweed and seaweed.

Orlando Lovell: Your WaterSchool M4H+ is quite an involved and complex project system. Could we start with you explaining to us what the M4H+ project is and why in this location?

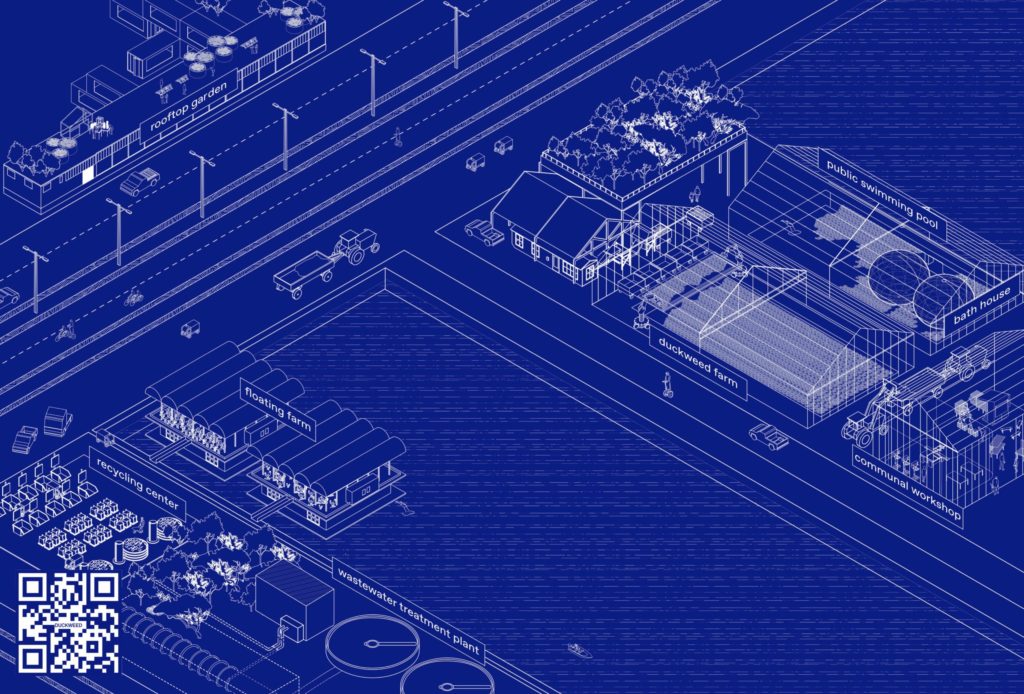

Rianne Makkink: M4H stands for Merwe-Vierhavens. It is a 100-hectare dockland area in Rotterdam in the Netherlands with a lot of warehouses that are vacant now that the harbour is closed. It used to be a citrus harbour, the place where all the citrus fruits, like oranges, entered Europe. Over the last ten or 15 years, a lot of designers, start-ups and offices have moved into this district.

The IABR (International Architecture Biennale Rotterdam) asked us to rethink the area as part of their 2020 biennial. The IABR focussed on two main topics for this. One is the energy transition away from natural gas. Because of what happened in Groningen [increasing local earthquakes resulting from drilling in the Groningen gas field led the Dutch government to resolve to cease all production there in 2022, ed.] we don’t want to use gas anymore, so all the housing has to transition towards another energy source. The other topic is water, which revolves around three general issues: there’s either too much, too little, or it’s too dirty.

Water revolves around three general issues: there’s either too much, too little, or it’s too dirty.

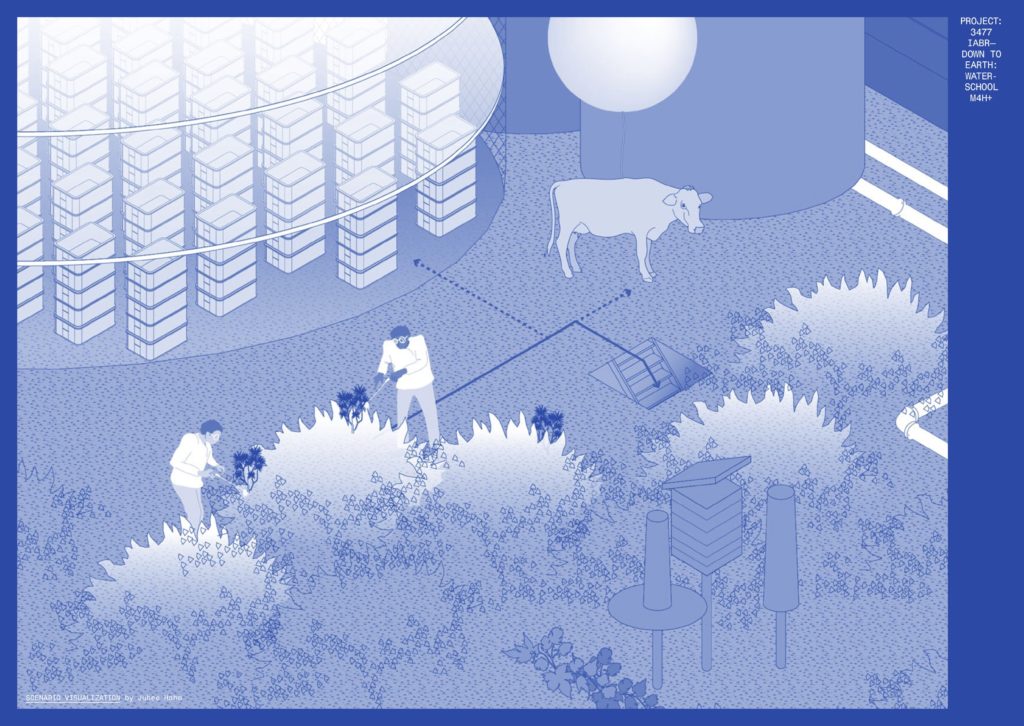

We, Studio Makkink & Bey, decided to focus on water, partly because we had already started working on a concept for a WaterSchool here back in 2018. So we were already using this area to think about a future we could want.

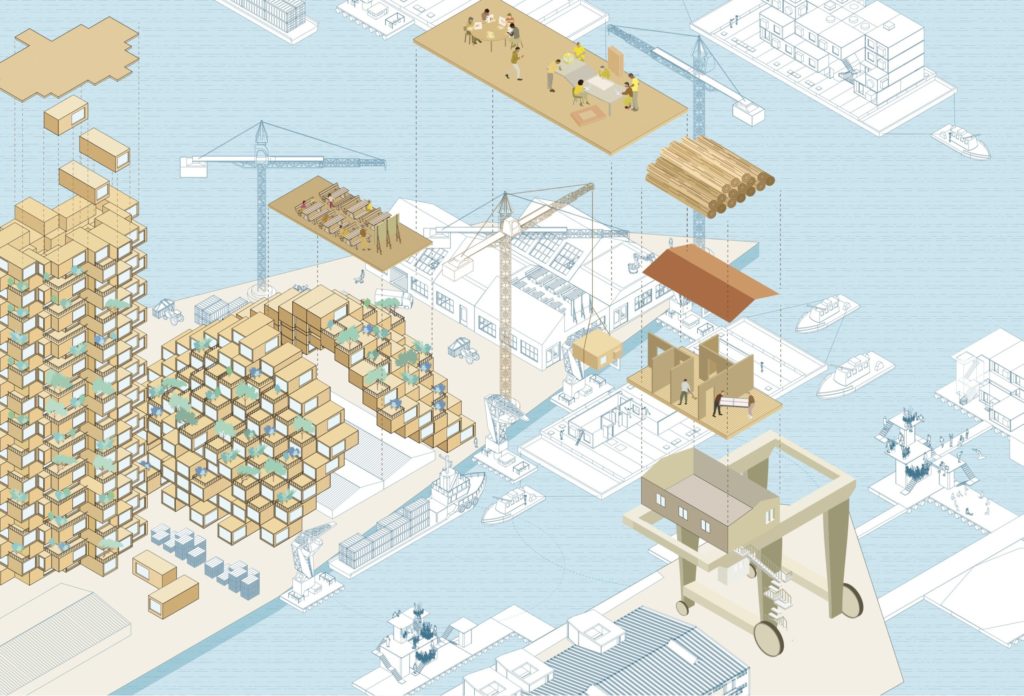

This is the last development space left in north Rotterdam and the municipality is very eager to develop housing here. They’ve been putting together a whole new programme for the area and are inviting a lot of new developments. These range from a brewery to harbour-related projects because they want to keep some harbour activity, which is interesting because it’s not tabula rasa. Usually, in urban design, you throw everything out and then build new housing, and then you say “living at the waterside, how nice”. But in this case, the harbour activities stay.

Sophie Lovell: Is the development a social housing project?

R: It’s absolutely not. The municipality doesn’t want that because Rotterdam is already a very poor area – it’s one of the poorest cities in the Netherlands, so they want to go for more for middle-class residents here.

But we developed our whole thinking [for the project] from an urban design point of view [that is oriented] towards food and materialisation of this area, and we want to include people from the poorer parts of the city within this. We have been trying to implement this in our exhibition by saying work is important; to give people proper work is one of the social development goals: less poverty, better education.

Our point of view is not about living per se, because living is only consuming, so we say “making”. We want to try out “working-living” as a topic. The emphasis on “living” in the Netherlands is still always very much the modernist view, where you live in one place, work somewhere else, and have your recreation somewhere else – everything’s put in boxes and nothing is experienced together.

O: What is the WaterSchool and how does differ from the usual urban plan here?

In 2017 for the Climate Action Challenge initiated by What Design Can Do, we proposed building a school in Dwarka, India, in order to address topics of water shortage and management and to show alternative ways to approach it. Since then, the WaterSchool has been a project that rethinks the economic and infrastructural model of education: we could produce everything it needs to function onsite through small-scale industrial collaborations with local designers and artists.

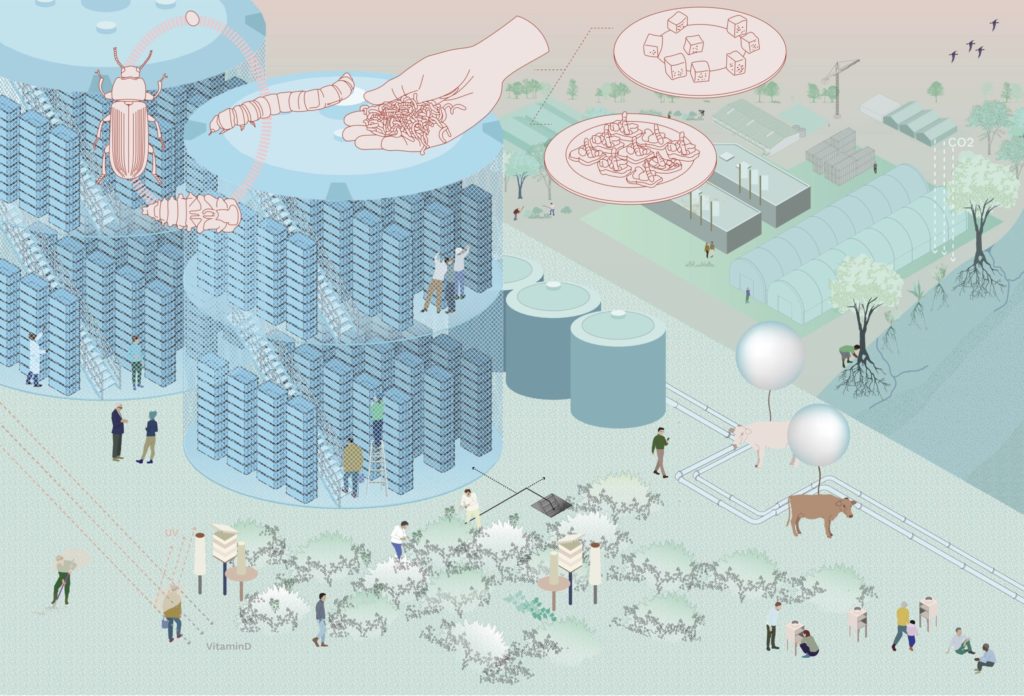

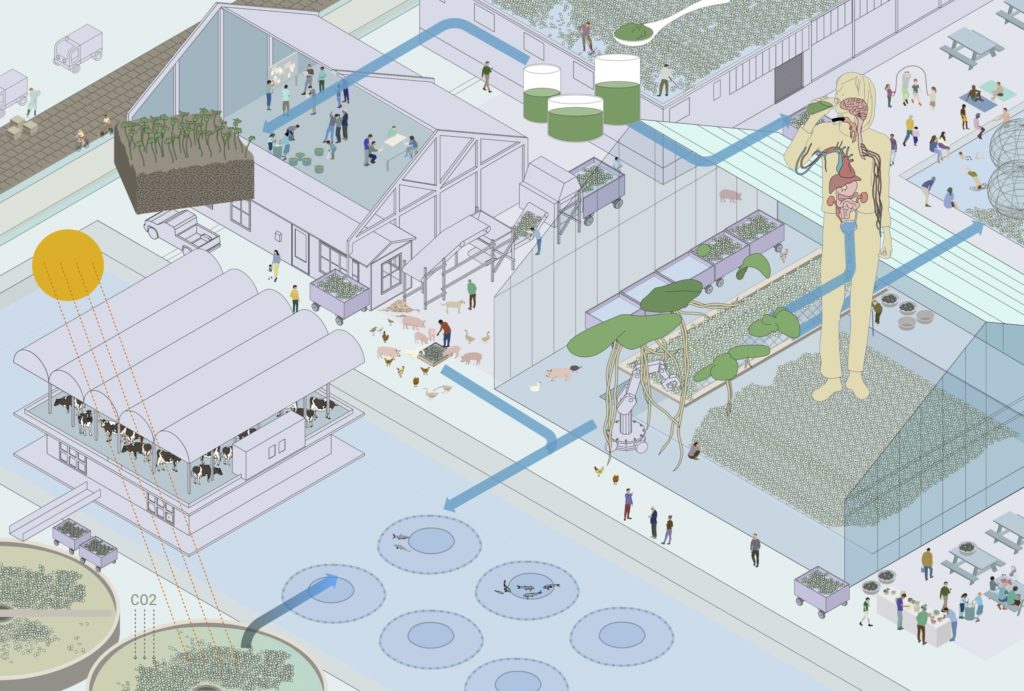

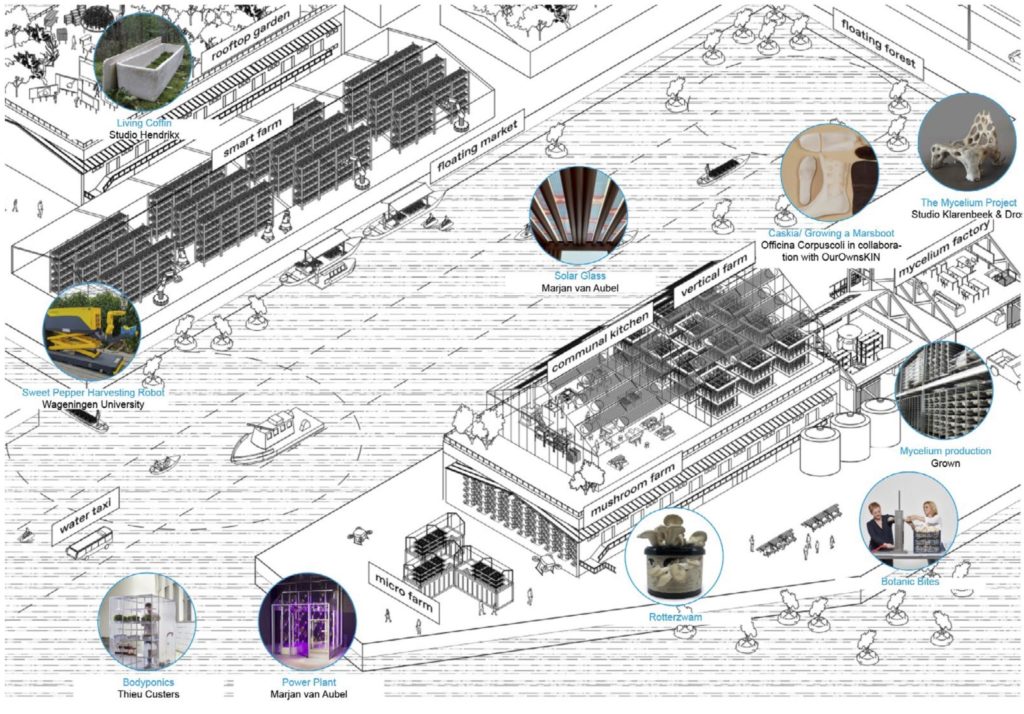

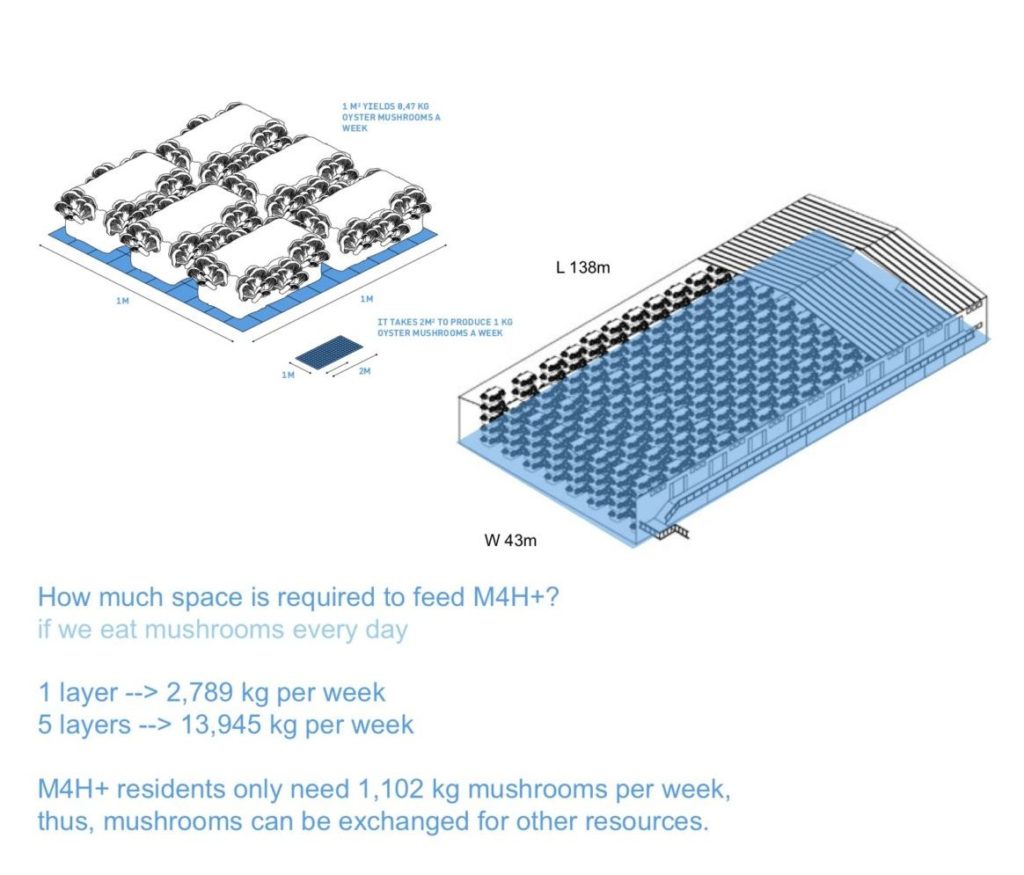

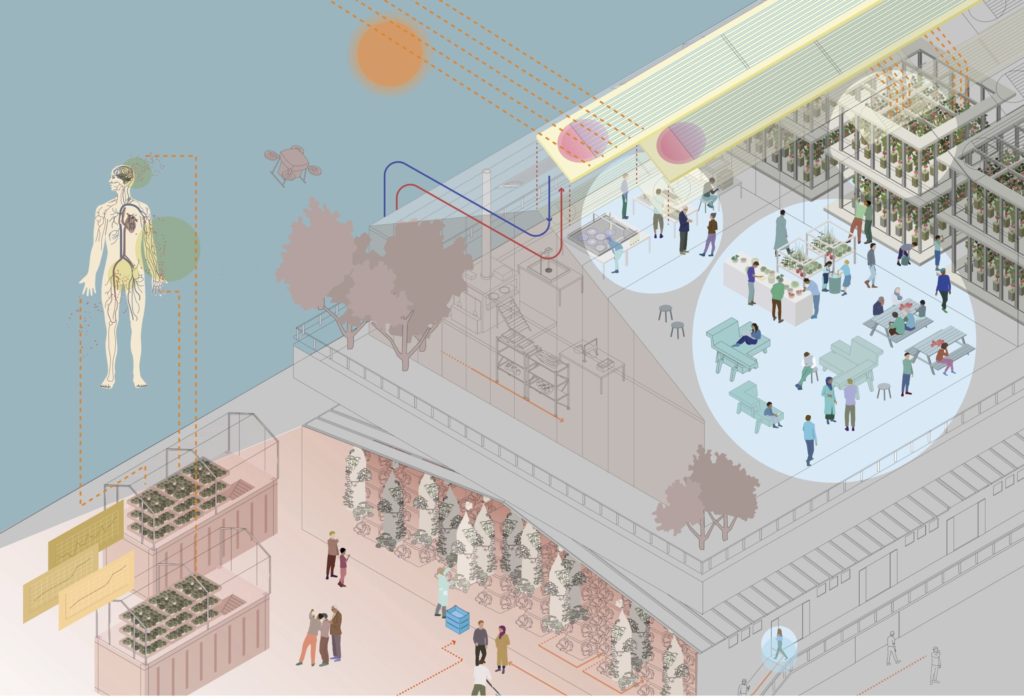

But now the context is a harbour area where at least 3,000 new houses and 6,300 new residents are coming in the near future, the first thing we thought about was: How could we feed this many people in a sustainable way? That’s when food resources with low environmental impacts, such as mushrooms, insects, duckweed, seaweed, came into the WaterSchool project. As a result, the WaterSchool M4H+ talks about not only water but also essential resources that could contribute to the area, and these resources became the starting points to connect different communities and disciplines.

Furthermore, we introduced new production environments based on the resources, which we called “production landscapes”. Unlike the usual urban planning, our approach is more about “learning by doing” through the WaterSchool, and we try to bring the knowledge and create educational hubs for people who live or work here.

S: So the WaterSchool M4H+ is intended as a catalyst for new cultures of living even though it’s a high-end property development?

R: Yes, but more from a working standpoint with more work-living; making a different kind of housing instead of these classic high-rise apartments, where there’s a cafe somewhere and an office somewhere else. We really want to create a place for production within this housing model.

S: With things like open kitchens?

R: Yes, open kitchens – or communal kitchens – are part of our “production landscapes”. We want to continue with this idea, to convince the municipality and the developers, because they haven’t given approval yet.

But they have always said that this area is a test site for experiments. So, for example, there is a floating farm here already that’s literally a farm on the water. It’s actually a ship – so just cows on a boat – and it’s there to show that water-related areas can also have cattle; to demonstrate the concept. But the nice thing about it is that you can now smell cows again, there’s not just the smell of cars.

O: Was the plan always to make realisable project elements and get the investors to implement them rather than just speculative ones; a functioning project rather than an experiment?

R: Yes, the office of the municipality and the harbour authorities were also our commissioners together with the IABR. They gave us the money to fund the projects because we are working in this area. The IABR has always made ateliers from real environments and contexts – for not only speculative but realistic changes.

What we’re saying is that developments are already happening here, so let’s just scale it up. There’s already a beer brewery, and a lot of designers are here too, lots of things are happening. We also want to have some cultural framework, because architects and urban designers are always so focused on the spatial framework. It’s not just about housing. We are asking: What kind of environment do you want to live in? What do you want to make? How are you going to live here? How do you want to live here?

I think our narrative is getting stronger all the time, partly because we really had to work hard to convince our commissioners to do it this way.

O: For the project, you made an exhibition, a website, booklets, library, podcast… so many different communication formats. Is all of it together helping you to communicate this complex system you have developed so that people understand it and are convinced to live it?

R: Yes, and now we are in the process of building our story together. Jurgen [the designer Jurgen Bey, Rianne’s studio partner and co-founder of Studio Makkink & Bey] works more on the narrative side, while I’m really more into the analysis. That’s why it’s good to have an exhibition. We began with the story of the Garden of Eden and the idea of starting again: How would you start again if you could? Then we worked on the water footprint and the materials themselves. The last thing we will do is to arrange it all as a complete narrative. Then all these elements can join together, otherwise, we’d be in danger of reproducing that same, separated, modernist viewpoint – of falling into a trap of our own design. I think our narrative is getting stronger all the time, partly because we really had to work hard to convince our commissioners to do it this way. They always want to see evidence, figures and proof.

O: Is that why you show a lot of data analysis in your booklets? Everything in the material seems fully calculated, which made me think: Which audience are these calculations for?

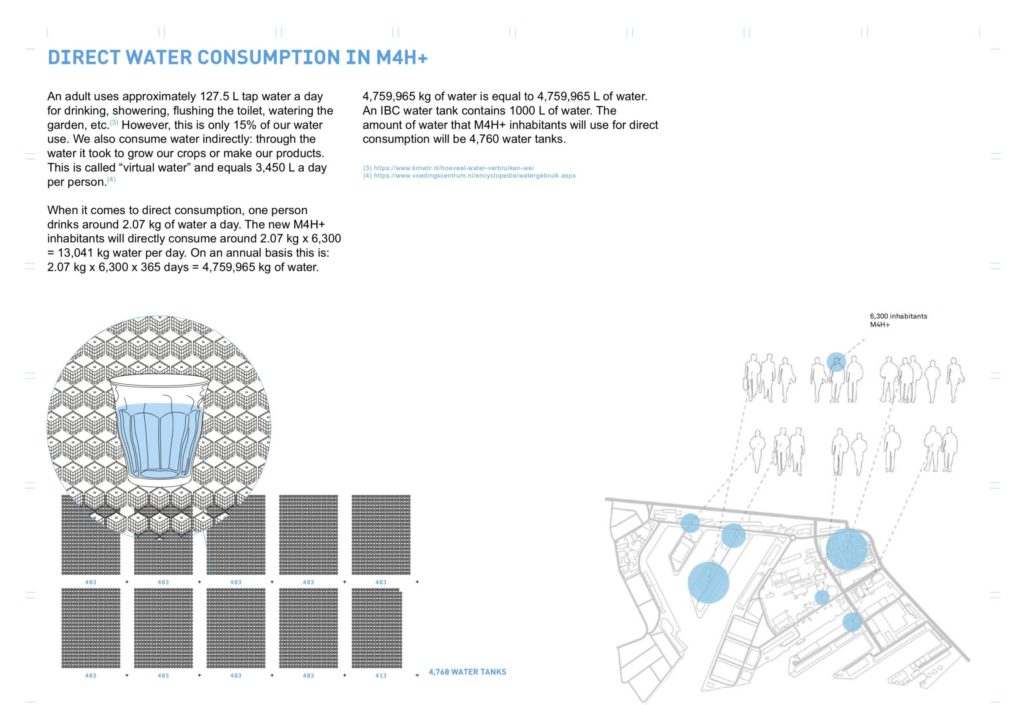

R: Yes, we also did this because we were interested in the human being itself. How much do you know about your body? How much do you know about your requirements, as a calculation? How much water do you use? Realising that here in western Europe you’re using 4,000 litres a day is really an awareness. You need to think about the alarming fact that you need so much water, and that water is such an asset. What can you grow with that much water?

S: The average individual water use in this region is usually considered to be around 100-150 litres per day per person – how did you arrive at this figure?

R: 4,000 litres of water consumption per day, per person is a more realistic figure. It includes all the water needed to produce food and other products for that person – so the more products you use, the more water you consume.

S: There’s always this danger with data, that you can make it say anything you want it to, depending on how you arrange the numbers, the questions and the parameters. Who (or what) did you work with on your data sources and your collaborations?

R: We worked with a group called the Water Footprint Network. They have these huge excel sheets with everything calculated with respect to water footprints, it’s enormous. But nobody can relate these numbers to daily life, it’s too much. So we converted amounts of water into barrel units. When you interact water footprint for the 4,000 litres a person uses daily, you can personalise it, you can factor in how much meat you’re eating, for example. And see what your water footprint actually means to you.

O: I feel there are multiple levels of audience in this – you have the initial audience of the architecture biennial, then you have a design audience because there are a lot of design pieces in the exhibition, then the developers and municipality and finally, hopefully, the locals in Rotterdam. Who do you see as your main audience?

R: For now there are different levels of audience, so we have different strategies. The IABR says we can continue, but who are we going to work with, going forward? Our first plan is to work with the municipality and the harbour authority, to influence their strategies for this new urban design development, especially their food-related strategies. They’re always thinking big and are they’re focused on big results. With food, they think if a project won’t provide for the whole area it’s not worth doing. But what if it’s good for 10 per cent? In our view, that’s significant. It’s also about visibility, so that people can see this is actually happening; that it’s possible to raise cattle here, for example.

O: I think there is a new shift in how design is perceived and exhibited to the general public. There is also a shift, especially in the Netherlands, toward exhibiting to people in authority positions who can make things happen. Designers have changed their communication and professionality with respect to the government or regulating bodies. It’s a new process, a new extra activation of seriousness because if you want to make significant change happen faster, you need to go to the top.

You can’t wait anymore. If you are always dependent on somebody else, it’s never going to happen.

S: There is also a much more networked understanding of the discipline within the profession. Like with architects, their strongest asset is that they are a nexus between communities, politicians, engineers, builders, materials and so on. They are the communicators that make all these connections happen through this building or that project. In your view, how has the role of “designer” shifted for you since you started?

R: Yes, and on top of that, there is a sense that you have to take charge now. You can’t wait anymore. If you are always dependent on somebody else it’s never going to happen. I also think you have to start new initiatives yourself, on a bigger scale. It’s also happening with architects, they are becoming developers now. They don’t wait anymore. They get investors alongside and then they develop a new building project. That way they also have better access to what they can make. Otherwise, architects had become only dressmakers for facades, there was nothing else for them anymore in the Netherlands. What’s happening now is that they start something and then Big Tech or big industry takes it over, and there is nothing in between. It happened to Eric Klaarenbeek with his fungi. You’ve heard of his inventing the use of mycelium as a building and insulation material? He tried to continue with it, he developed how to scale it up but the big guys came along and said “okay, thanks, it’s ours now, bye”.

S: I suppose this is a result of the gentrification of ideas, like the gentrification of urban areas: the artists and the creatives and designers feel they are out there pioneering and then the property developers come in and reap the profits.

R: Yes, they don’t take us seriously. They only say “it’s good, the way you imagine it” and they don’t believe you can develop it on a bigger scale. We need this middle industry again. That was also our goal here. We wanted to take the smaller industry here seriously, too. They said the food production concept was not enough to feed the 6,300 people in M4H, and they are right, but we are saying: even if it’s only providing 10 per cent of that need, that’s already a huge amount being produced within the city itself.

Nearly all the crops in the North-East Polder go out of the country. We have to rethink how we can keep production here on a more reduced scale.

O: Can I ask how you see the role of the farmer or the traditional food producer in this context? I know the Netherlands is very pioneering in high-tech food production and it also seems that if there are certain formulas for growing food, that can be taken and applied by anybody. Are there still farmers involved in your processes?

R: Yes, I think you still need this network of farming. If you think of growing fungi, for example, you still need the straw or hemp as part of the process and that is produced on an industrial scale. You might need another kind of farming though. Right now it’s all mass-produced and still quite cheap – that’s what Holland is famous for: cheap production, a lot of which is for export. Nearly all the crops produced in the North-East Polder go out of the country. We have to rethink how we can keep production here on a more reduced scale.

S: We listened to an amazing talk by Rob Hopkins at the 2021 Oxford Food Symposium a couple of weeks ago, talking about how to journey from high-carbon to low-carbon. He was saying that we need stories, because we need to dream fantastic futures that we long for, collectively – something that we want to build towards. You also talk about working with stories. How do you sell this kind of living concept? How do you get people to want to be engaged? Living this way is going to require adaptation on their part.

R: Narratives are important. On our website we have some future stories describing how one could imagine living here because it’s not just the future, the near future is already here! It’s only, as you say, this adaptation that needs to happen. The “WaterSchool” exhibition was a good start, but we now want to hold more exhibitions so more people get involved. It’s not that we invented anything new here – we just want to be the connectors for the moment. And we want to make more of these production landscapes, not just for the sake of making objects, but to illuminate the entire supply chain. People may only see the end product, but all the links in between are important to us.

S: So do you think you will need to work more with chefs, foragers or botanists to experiment with different kinds of fungi that you can eat, for example? I must admit that when I read about having to eat mushrooms every single day from the mushroom-growing facility, I wasn’t sure that was a future vision I wanted to experience. That’s where the project became slightly dystopian for me.

R: Yeah, perhaps it should not be taken so literally. There are already fungi-based vitamin supplements, for example. Also, duckweed and seaweed are in a lot of products already. Duckweed is not used for human consumption yet, but it’s coming. People need a lot of protein, and it has to come from somewhere. Like with insects: when we see them, we don’t want to eat them, but they are actually in a lot of products already. It’s just a question of cultural thinking.

We want to make more of these production landscapes, not just for the sake of making objects, but to illumunate the entire supply chain.

O: So what is the next stage for M4H+?

R: We have to find investors so we can do our research and continue the project. Maybe we will get small plots in the development to make it real, or perhaps we will get our own building, but we need investors. And we also want to put it on a European level, through the New European Bauhaus initiative, which is also a lot about food.

Rianne Makkink is a designer architect, the co-initiator of WaterSchool, and the co-founder/director of the Dutch design collaborative Studio Makkink & Bey in Rotterdam. The studio’s projects range from interior design through product design, public space projects, architecture, exhibition & shop-window design to research and applied-arts projects — a great number of which have been awarded prizes.

She has also has been teaching at several universities and academies within the field of architecture and design, namely the University of Ghent (BE), the Art Academy Linz (AT) and the Design Academy Eindhoven (NL) and the Technical University Delft (NL).

Read more about M4H+ WaterSchool here and Studio Makkink & Bey’s WaterSchool here.

Title image: IABR Waterschool M4H+Studio Makkink Bey, image by Aad Hoogendoorn.