LinYee Yuan, the founder and editor of MOLD magazine is a vanguard figure in future food publishing. She talks to The Common Table about designing the future of food, working in print and her recent return to place-based practice in the community.

Sophie & Orlando Lovell: Tell us a bit about yourself, what you studied and your early career path.

LinYee Yuan: I grew up in Houston, Texas but moved to New York to go to university and more or less never left – apart from spending a year and a half in Hong Kong. I studied Asian-American studies, which is basically critical race theory. Thanks to students who organised protests in 1996, I was part of the first generation of students who had access to an ethnic studies program at Columbia. It’s interesting because many of the same ideas I learned in college: structural racism, what it means to decolonise our perspectives, and the importance of prison abolition are now part of the mainstream understanding of our world. It’s a huge shift, one that is necessary in order to dismantle the extractive and oppressive systems and co-create something that is just and equitable.

And then you went into publishing, is that correct?

I love magazines and have collected them since I was young. They have always been a window into a world beyond the suburban experience that I grew up in. Whether it was teen magazines bought in Chinatown, talking about youth culture in Hong Kong, or magazines talking about life in New York, they were a way of immersing myself in different kinds of experiences beyond my day-to-day reality. After college, I worked for magazines basically my entire career – on both the business and editorial sides. I come from the print magazine world, from before magazines were even considered something that could be online.

Which magazines have you worked with?

I interned for Harper’s Bazaar when I was in college, I worked for The FADER magazine when I was in my mid-20s, and I worked for Theme magazine, which is probably still my favourite magazine, a magazine about Asian arts and culture. In my late 20s, I worked for The New York Times’ T magazine. And then I became Managing Editor of the industrial design magazine Core77, which was kind of my first foray into editing a digital magazine.

Did your interest in food grow in parallel to this?

As a first-generation American, food has always been very much part of my identity and also the way that I understood the world around me. My mother is a nutritionist and dietician, she worked at a local hospital for her entire career. My father is a very avid gardener and his singular passion in life beyond gardening is fishing. So, growing up, food has always been very much part of who I was and am.

Before the term “foodie” was even kind of in the mainstream context, if you were Asian American, you were definitely a foodie. I feel like foodie culture came out of this, it’s a very Asian thing. Also, if you’re from Texas, you love food, it’s part of the Texan identity as well. I’ve always had a very deep passion for food of all sorts. Moving to New York in my teens fueled that love. All of a sudden, I had access to all these things, like hummus – hummus was something I never had until I moved to New York and now it’s always in my refrigerator.

What you’ve described is a kind of emotional love for food and a personal and cultural connection. When you started MOLD magazine, on the other hand, you seemed to be coming from more of a design direction, with a focus apparently driven by a curiosity about the future of food and the relationship between tech and food and food design, which are not so much emotional as speculative.

Core77 was my introduction to industrial design. I worked there from 2010 to 2016. It was a really interesting time to be editing an industrial design magazine. With the arrival of the iPhone, there was this real kind of existential moment for industrial designers and a fear of the dematerialisation of culture. If you’re an industrial designer that doesn’t design objects, what do you do? Suddenly it was a big question. That really made me fall in love with discipline because although is a very process-driven, professionalised space, it is also one that is very thoughtful and reflective about its role in the world.

I’m not a designer but during this time I saw that there was also this burgeoning field of food design, which was just fascinating to me. There was a lot of student work coming out that was tackling questions around food and nobody was really writing about it. And so I felt this was an opportunity for me to just start a little project where I would write about food design projects on the nights and weekends because these were the things that I was really interested in. And that’s kind of how MOLD started – online.

When did this “little project”, as you call it, turn into a full-blown publication?

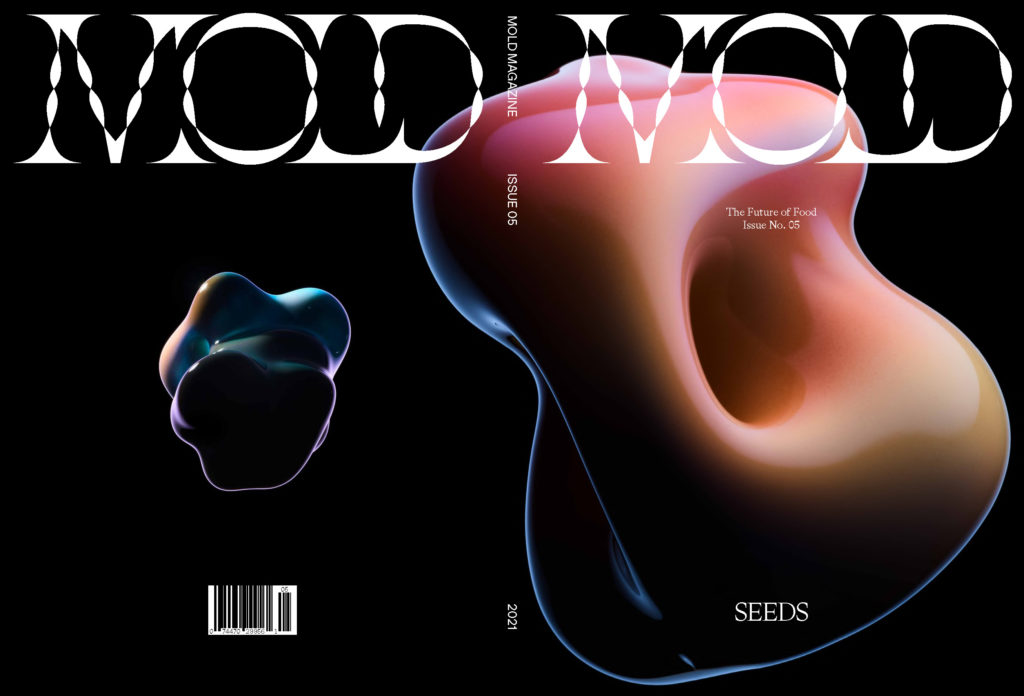

In 2016 I left Core 77 and launched a Kickstarter campaign to fund the first MOLD print magazine. It was always intended to be a finite print run of six issues. We’re working on the sixth issue right now.

Were you surprised at the response to the Kickstarter campaign to launch “the first magazine about the future of food” back then? You were looking for 34,000 USD and ended up being pledged 37,000…

I was very humbled by the number of complete strangers from all over the world who supported the Kickstarter campaign. I was actually shocked by that. I just thought it was gonna be my friends and my family, supporting me. I have no idea how they found it. It was 2016, and even the concept of food design was totally obscure at that point.

Did you do the whole thing by yourself?

I did it by myself in the sense that it’s my idea and I’m definitely the engine behind it. But as you know, making a magazine is not a singular pursuit. It’s definitely a very collaborative process. Thanks to just a little mix of luck with persistence I was able to find some really incredible collaborators.

Who else is on the MOLD team?

My boyfriend at the time, who is now my husband, and I went to meet a friend of his in London who was visiting from Copenhagen. It was at this very cute cocktail bar. She then introduced us to Johnny Drain who had spent some time at Noma and he and I just totally hit it off. We happened to have both contributed to a now-defunct French food magazine and I was like: “You’re the fermentation guy! I’m starting this magazine and the first issue is about the microbiome. We want to do some fermentation stories. Would you be interested in co-editing it with me?” It’s quite rare to meet somebody who is very science-minded (he has a PhD in Materials Science) but also can write. So he agreed to edit the first issue with me.

Simultaneously, I came across the work of an art director called Eric Hu, through a friend of mine. I reached out to him because his work is one of the few examples where I felt emotional about seeing a work of graphic design. So I just kind of cold-called him and said “Hey, I’m making this magazine about designing the future of food and I was wondering if you’d be interested in designing the first issue”. He replied that he was in the middle of moving to Montreal and starting a new job, but if I was open to him bringing on a collaborator, he’d be down to do it.

So that’s how we got Matt Tsang on board as well, who is also an incredible designer and art director. Now, six years later, we are working on issue no. 6 and it’s still the four of us doing it, along with another graphic designer Jena Myung.

Orlando, you were editing the now-defunct The DIFD (the Dutch Institute of Food and Design) before The Common Table, when was that founded?

I think around 2014.

Yeah. So as you know, it was still a very obscure subject at that point.

Yes. I was part of the second generation of students studying food design with Marije Vogelzang in the “Food Non Food” department at the Design Academy Eindhoven. Before I was done studying, I think I was in my third year, she asked me to work on The DIFD. That’s when I started, basically as the editor. I had so much respect for MOLD at the time, I thought you were some huge glossy publication with lots of staff and there I was, learning by doing, commissioning and running all the articles on The DIFD and running their social media channels by myself. It’s so nice and so interesting, all these years later, to meet you and hear your story.

I totally get it. That was why I started the print magazine because I was making this blog in, I wouldn’t say “obscurity” because there were people reading it, but I didn’t know that, right? And it was still confusing, even for my friends. They were all like: “What is food design, I don’t understand what you’re writing about. I don’t understand how this poster is food design”. So I decided that the most effective way of explaining my interpretation of food design was to create a design object that would explore different facets of what its potential could be.

By that point, I had already pivoted from publishing a food design blog to thinking about the future of food, and the role that design could play in offering solutions at different scales for the food crisis. And that is an example of the power of design.

I learned about the food crisis through writing about a poster project. The Australian designer Gemma Warriner, who was a student at the time, created a series of posters that translated a UN white paper’s warning into data visualisations. That FAO paper warned that if we continue to eat the way we do today, we won’t be able to feed the global population by the year 2050.

What for you are the most interesting kinds of projects in this, still very young, discipline of food design?

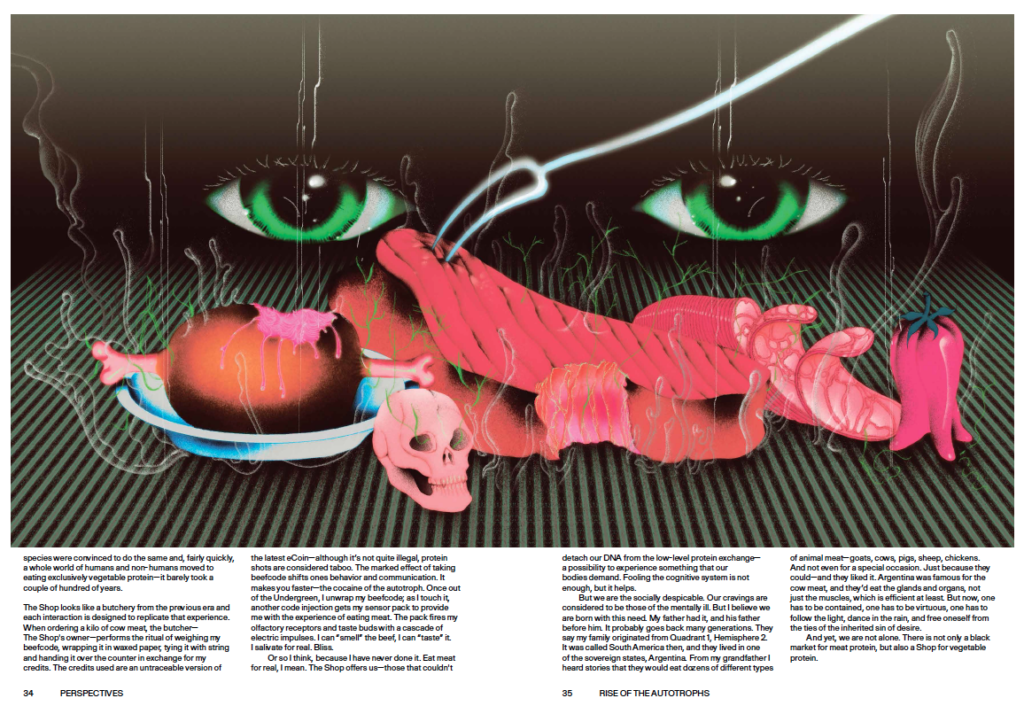

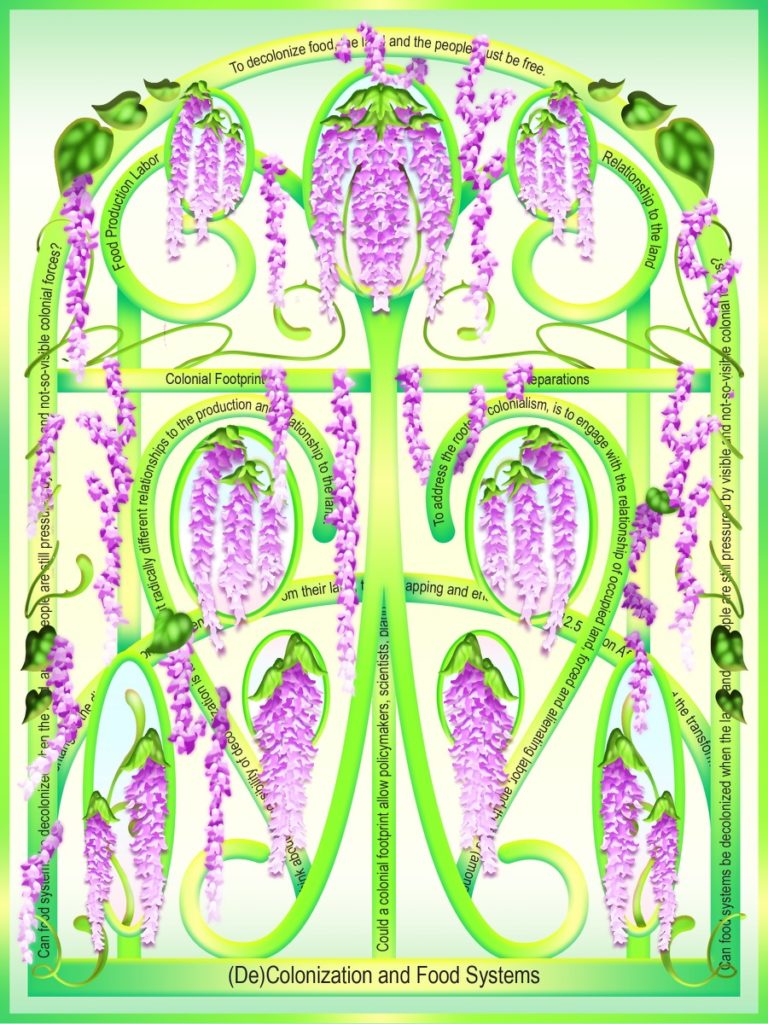

I definitely think the best food design projects are ones that are provocative and examine our relationship with food or reveal that we actually do have a relationship with food because as a society we’re often so far removed from it. I always like to refer to something the amazing scholar, environmentalist and food sovereignty advocate Vandana Shiva said in an interview that we did with her: that we always have to remember that the web of life is a food web.

I think about that all the time. It’s something that goes back to the ways that design has created this language around being human-centred. I feel like the Age of Enlightenment really created a separation between humans and other animals. The resulting consistent insistence that we are different, and not connected to other non-human beings is the foundation for things like capitalism and it represents an extractive mentality.

And implies that we are better or more important than other living things.

That’s right. It’s not about interdependence, it’s about domination and extraction. And that kind of philosophy is really the thing that has gotten us into this dead end of a dead end. So for me, the best food design is the one that recognises that we have a relationship with food and that we are all dependent on, largely unrecognised, multi-species networks that really hold the key to our continued existence.

You said you’re only planning on making make six issues of the magazine. Do you plan to continue MOLD afterwards? Or is it more like that’s the end of an experiment for you and time to talk about something else?

We’re still going to continue publishing online. I don’t know what lies ahead. I could continue talking about it for the rest of my life but maybe in five years, we’ll solve world hunger, and I don’t have to talk about it anymore. I would love to stop talking about it, be honest with you. The dream would be to stop talking about it because we’ve solved this very thorny, terrible situation that we’re in.

But realistically, that’s probably not going to happen. I like the idea that I started in a speculative space, examining whether the future of food was a technological one: lab-grown, etc. But over the years, I’ve come to realise that that doesn’t really make sense with my politics and it also doesn’t make sense given the realities of our relationship with the land and place as well as energy usage and power, and transportation.

So the next iteration of MOLD, beyond continuing to publish stories online, is where we’re starting Field Meridians, a nonprofit organisation that launched this summer. It’s about taking some of the product ideas and larger questions that we’ve been trying to answer through our editorial work, and really creating a place-based practice in my community here in Crown Heights, Brooklyn. We will be piloting different design projects here to engage our local community in questions around food sovereignty and food access. Our first project was a mobile kitchen that we installed in our nearby public park during this past summer solstice. It was designed and fabricated using found materials and featured a parabolic solar oven. We used the project as a way to share knowledge and ask our neighbours what their vision of the future of food would look like for Crown Heights. Our second project will take place during the Jewish holiday of Sukkot and we’ll be building a sukkah and hosting dinners there that will be open to the community.

So you’re pulling the focus right down to the local, to your immediate vicinity?

Hyper-local yes. The first project we did was at the park that I take my son to every single day. I feel very energised by the opportunity that lies ahead. I have two young children and I’ve lived in this community for 12 years; I’ve lived in New York for 24 years at this point and it’s time, I think, for me to put – as a cliché goes – my money where my mouth is and see what happens. It may fail in a spectacular way, I don’t know, but I feel like just doing the work is going to open up some really interesting conversations.

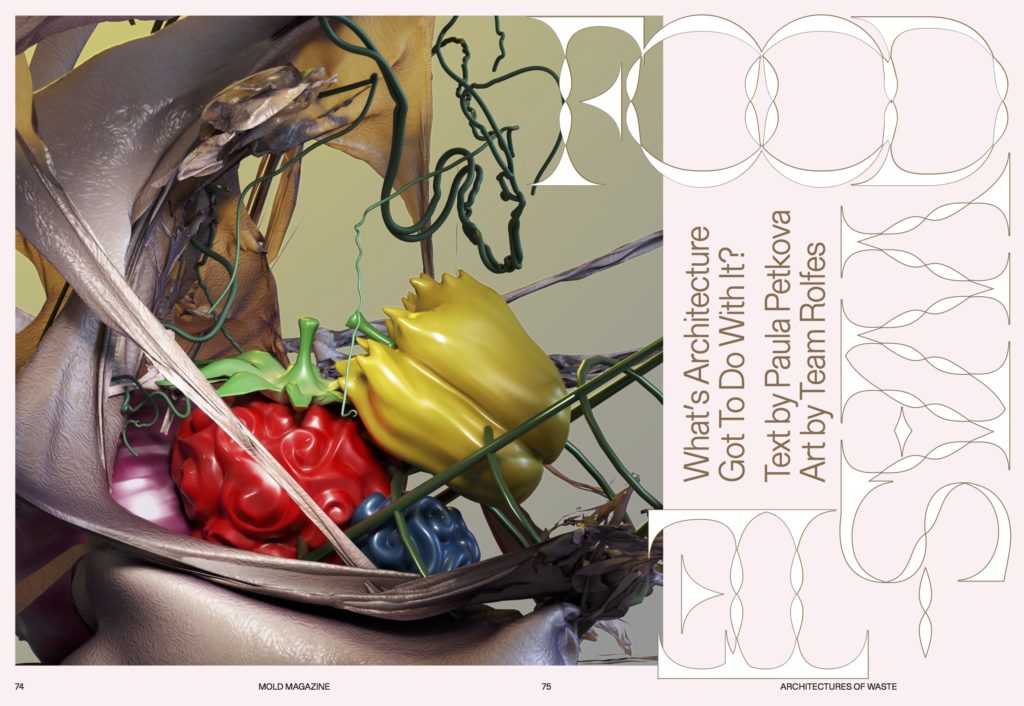

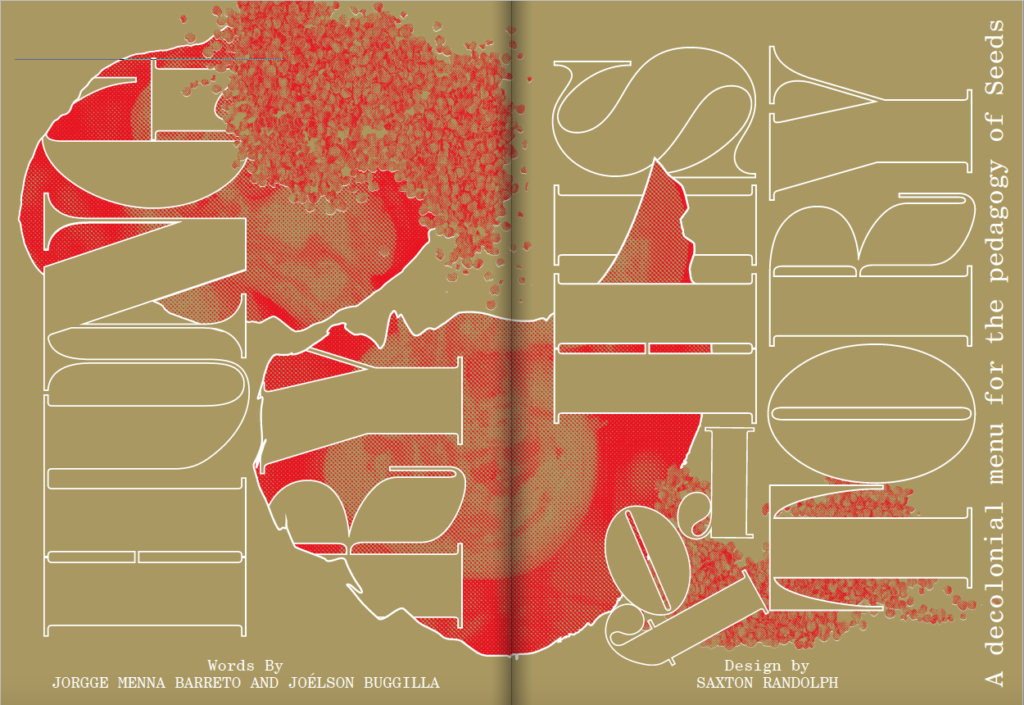

LinYee Yuan is the founder and editor of MOLD, a critically-acclaimed print and online magazine about designing the future of food. Through original reporting, Mold explores how designers can address the coming food crisis by creating products and systems that will help feed nine billion people by the year 2050. In addition to the website and a self-published print magazine, Mold hosts events and exhibitions; works with next-generation food and lifestyle brands and commissions products from emerging designers.

All images © and courtesy MOLD 2022; cover image from “Material Futures” by Marta Giralt Dunjo, photography by Justinas Velutis in MOLD issue 03: Food Waste.