Sara Harper is a former legislative staffer for the US Senate and founder of a platform that provides resources and connects people and organisations interested in regenerative agriculture practices. Danielle Schwab is on a mission to understand the global food and agriculture system. Here they talk candidly about getting brands and farmers to shift together towards regenerative practice, the futility of waiting for legislation, greenwashing in the organic field and the challenge of changing mindsets.

Danielle Schwab: Sara you have a goal similar to my own with Illuminate Food here in New Jersey. Namely to support farmers that are adopting more sustainable agricultural practices by connecting them to brands and businesses interested in sourcing directly and building relationships with farmers. Joining your community was pivotal in my education regarding agriculture and learning how disconnected farmers are from the realities of the food system. Could you perhaps introduce yourself and your platform Our Grounded Growth in your own words?

Sara Harper: I grew up in the middle of Kansas with wheatfields all around and farmers on both sides of my family. I came from agriculture but not the very picturesque red-barn view, from the really hard-work side. In fact, both of my parents got out of agriculture and wanted us [kids] to go and find something different – in part because it was such a hard life. So I went off to Washington DC and got into policy and politics, and then a job working on agricultural policy where I got to really learn a lot about agriculture. I did some consulting after that on environmental issues and sustainability. Then I really got to a point where I felt I’d learned so much and was so excited about the potential for agriculture to solve so many problems in our society – environmental problems, health problems – and yet I wasn’t seeing that happening in policy. It was very frustrating. I also wasn’t seeing it working one-on-one with individual companies and associations.

![Dr Rexford Tugwell [instrumental in creating the Soil Conservation Service in 1933] and farmer of dust bowl area in Texas Panhandle. President's [Roosevelt] report, July-August 1936. Photo Arthur Rothstein, courtesy Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. Read more about the dustbowl here.](https://thecommontable.eu/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/service-pnp-fsa-8b28000-8b28200-8b28201v-1.jpg)

When I was working in Washington, I realised there was a market for farmers to actually do these great things. It wasn’t called regenerative agriculture at the time, it was called carbon sequestration or climate-friendly agriculture, but it had a lot of the same principles. As I saw interest growing in some consumer segments and the national food industry for regenerative agriculture I thought: This is it! This is what I’ve been building my knowledge base up for my whole life: to be a matchmaker or facilitator for these emerging food brands that want to meet consumers who care about the environment, health, ethical sourcing and all these things. I wanted to help those brands connect directly to the emerging class of farmers working in unique ways that aren’t known about by a lot of people.

Now, getting this all the way from the field to the brand, to the consumer, is no easy task. So Grounded Growth is many things, but at its core, it’s a membership-based, online platform that I think of as kind of a mash-up between LinkedIn and a nerdy Netflix. It’s only for members, and when you join you’re able to talk with other farmers or with brands. So you get to know each other across the supply chain, which is unique in and of itself. I pull on my background in politics to help them not only get ready to be a partner with the other side of the supply chain; to get to know what they need, but also to bring them the resources to help build that path.

With nutrient-density testing, for example, we have a great resource in our network that helps farmers do that and helps brands understand what they can talk about with the test results. So it’s providing some strategy, providing messaging, providing a supportive community and then doing a lot of outreach for the group as a whole.

As Grounded Growth, I try to educate consumers, educate brands, do outreach, help them understand that if they can connect to this more positive way of growing food, not only would their businesses benefit because it’s what their consumers want, but it would also give them a legitimately good feeling about using their business for good.

In its simplest form, it’s farming with nature rather than against it.

You’ve mentioned a couple of things that people reading may not be up to speed on. Maybe we could just start with regenerative agriculture as compared to industrial agriculture.

In its simplest form, it’s farming with nature rather than against it. The other key concept is that it is restoring, regenerating, the natural resources that are involved in growing food, rather than depleting them. But it’s not easy, especially to get started when you’re growing a commercial crop. I think it’s important to say I came from the industrial agricultural world, so I understand some of why things have ended up the way they have, for economic reasons that aren’t maybe the best. Most of the farmers in our network started as conventional farmers, they didn’t start organic. But through the process of improving their soil quality and health – which of course gives them a better outcome and costs less money – they have added more and more regenerative practices.

If you’re depleting your soil in a conventional agriculture sense, what that means is you’re applying pesticides and chemicals to help you get the outcome and yield that you want. But if you’re not regenerating or restoring the soil microbiome underneath, then you’re going to need more chemicals each year because you’re going to have less fertile soil.

The regenerative process is not something you see overnight, it takes a while for the whole system to respond. It’s very similar to gut health. If you take antibiotics, for example, it kills off all that gut health and you have to build it back up and restore it. It’s amazing how similar our guts are to the soil. These farmers are using practices that add more nutrients and unlocking soil’s natural ability to heal itself. Various practices that heal the soil, clean the water and are better for the air too, and they’re able to produce similar yields to conventional farmers. They’re not taking a huge yield loss. And if they are taking a yield loss, they’re still more profitable because they’re not spending as much on chemicals.

Until a couple of years ago I think a lot of us, including myself, didn’t make the connection between the environment and food. We used fossil fuels to expand our society, then realised it’s not sustainable and is destroying our environment. We now also realise that giant agriculture with chemicals and fertilisers also won’t last, and we have to change our ways. Unfortunately, there doesn’t seem to be a lot of interest from governments in renewable energies and agriculture although, yes, there’s the private sector because it’s a smart business decision. I don’t know if it’s a matter of time but at the moment you might be one of the only peeps in the room. I know we focus on what some consumers and farmers are doing and that’s huge, but there’s also a massive gap at the policy level. Why is that, and is change coming in your opinion?

I am very pessimistic about policymaking, especially now. You can’t really have a policy when you have the partisan divide that we do.

I felt like I got three educations working on Capitol Hill. One of those was understanding how policy works and how it doesn’t. I think that really lasting policy follows a successful market example, it doesn’t lead it. In some cases maybe you have a really bad disaster that gets people’s attention and you get something like the Clean Water Act or the Clean Air Act. But those things aren’t renewed or updated very often, and they’re pretty much just sent off wholesale to the agencies to figure it out. The EPA [U.S. Environmental Protection Agency], essentially, is “updating” policy, and there’s a place for that, but you’re not going to lead a force through the EPA. I’m not saying there’s no place for it, but our system is designed to make regulations very hard to pass and easy to stop so that we don’t have these big swings when one side comes in [to power] and puts in lots of stuff and then the other side gets in and undoes it all. Because of this, if you have a successful design in the market that policy can get behind and codify, then that tends to work well and tends to last.

I am very pessimistic about policymaking, especially now. You can’t really have a policy when you have the partisan divide that we do, which is in fact another protected feature of our government because the founders were very concerned about partisan factions and the damage that can do. That’s the system. If you have really sharp divides – as we do – and protections for minority viewpoints, in the Senate especially, then one senator can kill pretty much anything.

Because of all that, it’s very hard to come in with a sweeping idea and not only get it through but get it implemented. But it is possible is if you have a positive example from the market. If you can point to something that works in the market, you’re showing that it’s palatable, it’s stable, it can be done without crushing business. So my focus on the private market is not only because I think it moves much faster, but also because good policy can then come behind and do what it’s supposed to, which is to codify and standardise.

So what would be the dream scenario to get the consumers on board, get some brands on board – what is that leap to standardisation and policymaking – from small-scale matchmaking to the bigger picture?

Part of it goes back to what you were saying at the beginning: What is regenerative? It’s this very big, vague thing and people have different definitions of it. If you could demonstrate a real consumer desire or value for it, then there might be interest in having some kind of policy that defines what regenerative is. I’m not even necessarily saying I’m for that because it’s a whole political battle, but that’s why it would be nice to have the market play out some of these different things. It would be nice too for people if there was a regenerative label somewhere like what the USDA [United States Dept. of Agriculture] has done with organic.

Consumers are not aware that organic requires a lot of tillage, which we now know disrupts the biome just as antibiotics disrupt our gut.

Mentioning “organic” reminds me of a word you used at the beginning: “greenwashing”. We know that once a word is trendy like organic, marketing takes over and it really loses what it means in reality. Words like “natural” and “sustainable”, that are trying to connect emotionally to what the consumer is looking for, then lose their real-world impact. So maybe you could introduce greenwashing and how you’ve seen it play out with organic.

One of the things I wish our culture as well as we as individuals would work on is getting away from this black and white, all or nothing, good and evil thinking. There’s so much in between. Consumers have embedded the idea of perfection into the idea of organic. They’re not aware that organic requires a lot of tillage, which we now know disrupts the biome just as antibiotics disrupt our gut. Organic can use pesticides – they’re natural pesticides, but arsenic is natural! And whenever you have a market that’s so popular with so many imports coming in, you get fraud – like people thinking that they’re getting organic at a farmer’s market when they maybe are not, for example. There’s not necessarily an incentive on the organic side to correct the perception people have of it when they’re getting up to three times more than for the same product that’s not organic.

Some greenwashing is around things that people just don’t know about. Some of it is actively fooling the consumer. For example, the pesticide issue: organic doesn’t use synthetic pesticides, but pushing on the fear of all pesticides pushes you to buy organic. But that isn’t the only issue for health. The nutrient density of food is an issue too. We don’t know if organic is more nutrient-dense than regenerative practices that may use some chemicals – far less than conventionally – but because they don’t till, the microbiome in the soil is far healthier. But we do know from some of our farmers that it has led to higher levels of zinc and iron and calcium in the food that they grow. So, what’s the trade-off there? Some tiny bit of pesticide use, with the crops being tested for zero pesticide residue? This is a complex issue, but people have 30 seconds to decide what they’re going to buy in the store.

Organic gives you a number of things but it isn’t the full picture and this could be.

Let’s talk about the supply chain, which is just as complex. Maybe you can talk about why it is so hard for brands to work directly with farms and your insights into how the supply chain works currently.

I think the biggest thing is that the supply chain was built to meet different needs and wants to what we have now. It was built to maximise safe, cheap food and that’s what it does really well. Cheap because it’s subsidised and also very efficiently transported and processed. There’s a beauty and environmental benefit in efficiency that sometimes we don’t fully appreciate. So there are good things about that system. On the health side, we have so far cut back on illnesses caused by bad or rotten food, and so on. My hope is that we can keep a lot of that and then also branch off and create a supply chain that, like organic, is separate, and brings to the market this much more nutrient-rich food that’s better for the environment and creates all of these benefits that consumer research says over and over again people want. And we’re back to the greenwashing thing: I think people think they may be getting that by buying organic. Organic gives you a number of things but it isn’t the full picture and this could be.

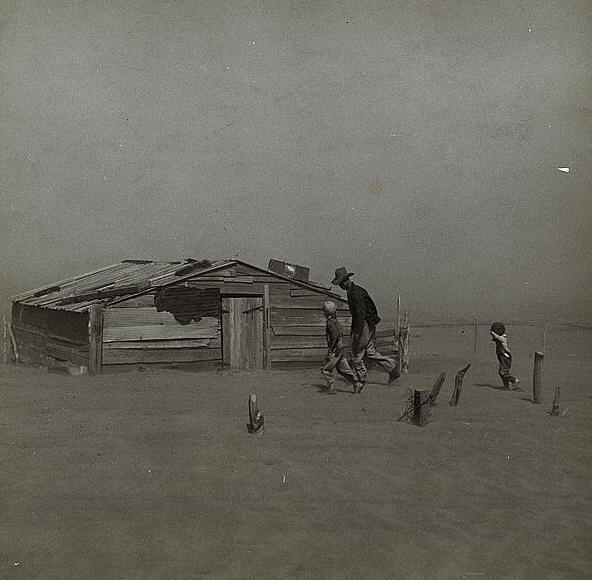

![[Untitled photo, possibly related to: Cimarron County, Oklahoma. April, 1936. Dust Bowl], April 1936. Photo: Arthur Rothstein, courtesy Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C.](https://thecommontable.eu/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/service-pnp-fsa-8b38000-8b38200-8b38285v-1.jpg)

But it’s hard is because the current system doesn’t want a competitor. Here’s the thing: organic farmers have significant yield reduction, maybe less so now, but initially they did. But these regenerative guys are interesting because they have significant yield, they can be a significant size and yet deliver really measurable benefits. You can test the nutrient density of the crops they grow. You can test the effect on the environment, the impact of the carbon that they’re storing in the ground. So really concrete positive data, and yet they’re big commercial farmers that could supply big brands if there was a way to get it there.

Why is it that the marketing guy or the packaging guy and the Instagram influencer are all getting their 30 per cent, but the farmer isn’t?

The other part that we’re trying to disrupt is the idea that the main ingredient in a product is the cheapest part of any product you buy. If you buy a box of cornflakes, ten cents of that is the corn. It’s insane. I’ve been in negotiations with mills trying to get some of our regenerative wheat farmers to market. We’ve set forth a price that’s kind of in-between organic and conventional. The mills will say: That’s just no go! Everyone has to add their 30 per cent on top. But that has to change. Why is it that the marketing guy or the packaging guy and the Instagram influencer are all getting their 30 per cent, but the farmer isn’t getting their 30 per cent mark-up? Not even close.

If as a society we want all these benefits – healthier food, good for the environment, good for local communities – then we have to pay the people. The only person who can do all that is the farmer. The marketer can’t do it, the packager can’t do it, the transporter can’t do it. Yes, there’ll always be a need for the middle people because, of course, the farmer can’t change his wheat into bread. But there needs to be a recalculation of who’s providing the value and, if we’re going to keep the same price, how does that 3.50 USD, or whatever, get chopped up in a different way so that the farmer gets more than ten cents of it. If not, how are you ever going to get farmers to take the risk of changing their practices? They’re putting their whole businesses on the line.

You’re not going to see a politician stand up and say, “Crop insurance reform for regenerative agriculture!” You’d be a hero if you did but the press wouldn’t cover it.

Going back to policy, this is where a policy piece could help: some of the things that the farmers do put them at risk of losing their subsidies. For crop insurance, for example, that’s an easy fix, but it’s not big and glamorous. You’re not going to see a politician stand up and say, “Crop insurance reform for regenerative agriculture!” You’d be a hero if you did but the press wouldn’t cover it.

When you get to the level of individual action, you don’t have to be interested in crop insurance or all those weighty things, but you have to support some of the people who are. You have to really look at what you actually get for the time you spend advocating for something or the money that you spend buying a product – and who can get real results and measurable outcomes. It’s like an internet scam – if someone’s holding something out in front of you that sounds too good to be true, you should do your research first. When you’re being sold a product or a message , if there’s not some piece of it that’s in-the-weeds or nerdy or involves trade-offs, it’s probably not real. That’s just the way it is. Change happens in a step by step, not very glamorous way. But that’s the change that lasts.

I want to bring us to one more point as a final conversation topic, which is the “why” for farmers. This is what being part of your network and going on my road trip and meeting farmers helped me see – that it’s not a decision to go regenerative because consumers want it, it’s a decision to save their land because they’re the stewards of it. To me, that’s the strongest point. Transitioning to regenerative or organic because you can get an extra dollar is fine, but it’s a completely different story when it’s because you want to have a future for generations on your land.

I’m very big on the market incentive and I fight hard for farmers to get paid fairly for the value they’re providing and I’ll continue to fight for that. But you’re right, the core of regenerative is the mindset shift that a lot of farmers talk about. One of the coolest things I heard a farmer say is how he used to look out on a cover crop, which is many different plants growing just to cover the land and not be harvested, and used to see it as competition – it was competing with him for the moisture in the soil, the use of the soil, and so on. When he went through the process of transitioning to regenerative, he came to understand that that cover crop represented synthesis: “That cover crop is protecting the soil for my crop. That cover crop is unlocking nutrients that my own crop otherwise would not be able to have.”

The core of regenerative is the mindset shift that a lot of farmers talk about.

You can’t really scale that mindset shift up by just holding out a dollar figure. But it’s a shift that needs to happen for the farmer to take the risk and continue taking the risk. I think all farmers should shift towards regenerative because it does save them money and it does extend the life of their land and the generational transfer that they could do. And it makes farming fun again. You’re playing with biology again, you’re working with and tweaking nature instead of trying to control it – it’s just fun.

An important point is that the inherently risky nature of farming tends to make farmers more conservative. So they tend to watch what their neighbours are doing, and if those neighbours try new things and do well and make it work, then adoption spreads. Recently in our network, two of our brands pledged one per cent of their net sales to help a farmer apply a five-species cover crop that he had never done. It went so well and the farmer got so much benefit for it, they then expanded that practice to 4,000 acres on their own. That’s what can happen when you have this combination [of farmer and brands]. It doesn’t have to be in the form of a premium, it can be in the form of a partnership. Smaller brands in particular it can be very flexible and find ways to support the farmer.

At the end of the day, the outcomes [with regenerative practice] are so great that while we want it to be a full mindset shift, some will do it simply because the numbers are better. At the same time, even with all the market pull that organic has, it’s still just one per cent of farmland in the US. It’s still that small. My point is that [our system] is a hybrid system where you could have a significant scale. You could have great numbers of conventional farmers shifting towards levels of regenerative that give us different benefits and reductions in chemicals, especially if there were more of a market premium for it.

Danielle Schwab writes about food supply chains on her website, Illuminate Supply Chains, to help educate consumers about where their food comes from. She is also the founder of Illuminate Food, a platform to help consumers connect to where their food comes from. Their mission is to support small-scale farmers by sharing stories and creating a curated farm box for those living in the New Jersey area.

Sara Harper worked as a legislative staffer on agricultural, environmental and other issues in the U.S. Senate from 1999-2003. She drafted legislation that would have paid farmers for adopting what are now called regenerative farming practices in exchange for measurement information provided to USDA about how much carbon was stored in the soil. This information would have laid the groundwork for farmers to be paid for the benefits they provided in fighting climate change. After her time on the Hill, Sara continued to build support for regenerative farming by building political and policy alliances between farmers, environmentalists and Republicans on the issue of climate change for the national non-profit, Environmental Defense Fund. More recently, she worked as a sustainability consultant for U.S. national farm associations and global agribusiness companies in the private sector. In late 2017, Sara launched Grounded Growth, LLC — a unique, online platform that provides the resources, strategy and connections needed to bring regenerative agriculture to market in a way that helps restore consumers, the planet, food producers and farmers.

This discussion is based on a podcast interview for Illuminate Your Plate of Sara Harper, founder of Our Grounded Growth, by Danielle Schwab, founder of Illuminate Supply Chains, October 2, 2020. Reproduced in an edited form here with kind permission.

Title image: Dustbowl farmer driving a tractor with his young son, near Cland, New Mexico. “I left cotton-growing east of Wichita Falls to come out here to get to grow wheat. [The superior status of wheat over cotton farmers is traditional.] I guess I’ve made 1,000 miles right up and down this field in the dust when you couldn’t see that car on the road and had to use headlights. This soil is the best there is anywhere, but it sure does blow when it’s right. If you stay in the house and wait for the dust to stop you won’t make a crop. But I’ve seen only one year since I came here in 1920 that I didn’t make something”. Photo Dorothea Lange, June 1938, courtesy Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C.